April 21, 2025

Contact: Sara Diedrich, diedrichs@missouri.edu

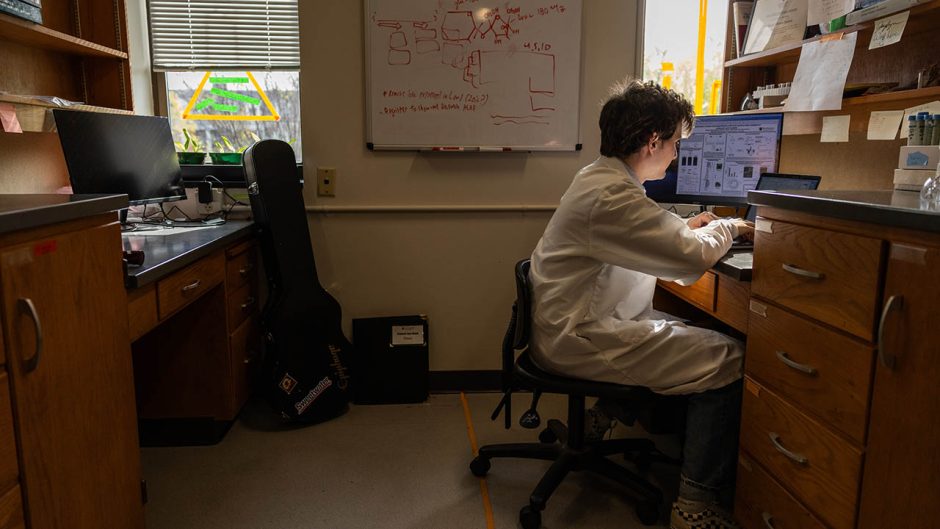

Photo by Abbie Lankitus

From a young age, Will Thives Santos dreamed of turning his passion for the guitar into a professional music career. He enrolled at the University of Missouri to study music.

However, an unexpected gap year due to the COVID-19 pandemic led him to reconsider his path, sparking a newfound interest in science and an unforeseen calling — one that blends the discipline of science with the creativity of music in ways he never imagined: research.

“I think creativity goes a long way in science,” Santos said. “One of my favorite parts of being in a lab is exploring creative hypotheses and wondering where the research could lead. It’s that drive to discover something new that excites me, just like creating music.”

Today, Santos, who grew up in Brazil, is a senior majoring in biochemistry with a minor in jazz studies. During his time at Mizzou, he has amassed nearly four years of research experience in a plant lab on campus and has recently published a research paper with his mentor and the lab’s principal investigator, Craig Schenck, an assistant professor in the Division of Biochemistry in Mizzou’s College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. Beyond the lab, Santos plays guitar with the university’s Concert Jazz Band and is a member of an alternative rock band called The Park with five of his friends.

At Mizzou, Santos has found his rhythm — both in science and in sound.

Seeds of discovery

Early in his freshman year, Santos realized he wanted to couple classroom learning with hands-on experience and real-world scientific discovery. He found exactly what he was looking for in Mizzou’s Freshmen Research in Plants, or FRIPS, program — an initiative designed to introduce new students to the world of plant research. For Santos, it was the perfect gateway to research and a glimpse into what a future career in science could entail.

Eager to get started, he joined Schenck, who arrived at the university in fall 2021, and his plant lab in Schweitzer Hall. As two newcomers to Mizzou, Santos and Schenck wasted no time and got to work, diving into the lab’s mission of studying how and why plants produce so many chemicals. Their research focuses on a toxic compound — azetidine 2-carboxylic acid — that some plants produce as a defense mechanism.

It didn’t take long for Schenck to recognize his protégé’s natural curiosity and eagerness to learn — qualities that would become the foundation of Santos’ journey into scientific discovery.

“I know how valuable undergraduate research is because that’s how I got my start,” Schenck said. “So, when I started my own lab, I made it a priority to mentor as many undergraduate students as possible.”

And Santos quickly became a key part of the team.

“Will is highly creative and an exceptional problem solver, which makes his contributions in the lab invaluable,” Schenck said. “His creativity is particularly beneficial in research, a process that often mirrors learning an instrument — it can be frustrating, especially when things don’t go as planned. Just as a musician refines their technique through practice, research requires constant tweaking and modification to improve the outcome.”

Partners in the lab

Schenck said that unlike some who are new to research, Santos isn’t discouraged by setbacks.

“Will understands that failure is an integral part of discovery,” he said. “His creativity serves as a springboard for his work in the lab, driving innovation and progress.”

For Santos, being treated as a partner in the lab built his confidence and sparked his joy for shared discovery.

Now, Santos will continue his research as a doctoral student in biological engineering at Mizzou. While he has yet to decide between academia and industry, his passion for discovery remains his driving force.

“With my music, I have always loved playing for others, sharing moments that bring people together,” he said. “With my research, I am contributing to the field, knowing that my research is expanding our collective understanding of biochemistry, biology and other sciences. Just as I have built upon the work of those before me, I hope that future scientists will build upon mine. Twenty years from now, I want someone to look at my work and see how it helped shape their own discoveries.”

The study

Scientists know that some plants use certain chemicals, called toxic metabolites, to compete with other organisms for resources including space and nutrients. These chemicals can target essential processes, such as protein production, to harm neighboring plants. The problem has been that scientists don’t fully understand how these chemicals work or how plants defend against them, which limits their ability to use this knowledge to improve crop resilience.

But a recent study from the University of Missouri discovered how one such naturally occurring compound disrupts plant growth ─ perhaps one day offering farmers a sustainable solution for controlling invasive plants.

According to the study, azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (Aze) disrupts the growth of plant roots by being mistakenly incorporated into proteins in place of the amino acid proline (Pro). This causes the proteins to fold incorrectly, leading to a stress response in the plant. The researchers used a variety of scientific techniques, such as testing plant growth on plates, analyzing chemical changes and studying protein production, to show how Aze triggers this stress.

By understanding how Aze works, this research gives insights into the broader role of these harmful metabolites in plants and opens possibilities for using this knowledge to manage plant growth or stress responses in agriculture.

“Mechanism of action of the toxic proline mimic azetidine 2-carboxylic acid in plants” was published in Plant Journal. Co-authors, all from Mizzou, are William Thives Santos, Varun Dwivedi, Ha Ngoc Duong, Madison Meiderhoff, Kathryn vanden Hoek, Ruthie Angelovici and Craig A. Schenck.