By Eric Stann

Sept. 9, 2025

Contact: Eric Stann, StannE@missouri.edu

A new study from the University of Missouri is helping veterinarians and pet owners better understand how to treat thyroid cancer in dogs by studying how to improve treatment with a type of therapy called radioactive iodine. It lays the important groundwork for delivering more tailored and effective treatment options.

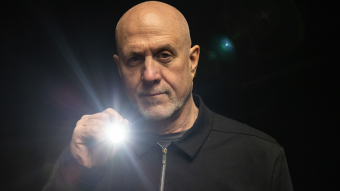

“The integration of radiopharmaceuticals and advanced imaging techniques is fundamentally changing canine cancer treatment by enabling more precise diagnostics, personalized treatment planning and a deeper understanding of tumor behavior, particularly in the context of thyroid cancer,” said Charles A. Maitz, associate professor of radiation oncology at Mizzou’s College of Veterinary Medicine and one of the study’s authors.

What made this study unique, Maitz said, is that it focused exclusively on 32 dogs treated with radioactive iodine alone, without surgery or chemotherapy. This allowed the team to isolate and evaluate the specific effects of radioactive iodine to better understand what factors influence how well the treatment works.

Before receiving treatment, each dog underwent specialized nuclear imaging to examine its thyroid tumors. Then, the researchers used a cutting-edge technique called radiomics to analyze the scans, looking for patterns that might predict how well a dog could respond to therapy.

Radiomics involves extracting large amounts of data from images such as CT or PET scans. Each scan is made up of thousands of pixels, each of which reflects how much radiation was absorbed in that tiny area of tissue.

Unlike traditional medical imaging, which relies on a radiologist’s interpretation, radiomics uses powerful computer programs to find tiny details —texture, shape or variation — that aren’t visible to the human eye. This helps veterinarians get more useful information from standard scans.

“Radiomics uses hardcore computing power to analyze the statistics of these pixel values and their relationships,” Maitz said. “It reveals subtle differences and useful information that could be key in understanding tumor behavior.”

One of the study’s key findings was that dogs who received a higher amount of radioactive iodine tended to respond better to the treatment.

Maitz suggests that tailoring the dose of radiation more precisely for each dog — based on individual factors — could improve outcomes and potentially lead to more targeted care in treating thyroid cancer in pets. That means more dogs may benefit from radioactive iodine therapy than previously thought.

“This really highlights the need for dosimetry — actually measuring how much radiation reaches the tumor — rather than relying on the amount we give,” he said.

Researchers also found that signs of illness and whether the cancer had spread to the lymph nodes affected results. For long-term survival, it mattered whether the cancer had spread to other parts of the body and how much of the radiation was absorbed by the tumor compared to nearby salivary glands. Without treatment, the dogs typically succumb to the disease within six months or less.

A translational approach to cancer care

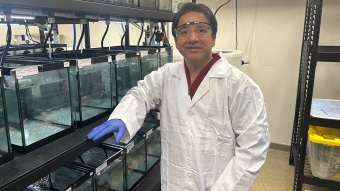

In addition to his role in the College of Veterinary Medicine, Maitz is a researcher at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR), where he focuses on radiopharmaceutical development — the use of radioactive compounds to diagnose and treat disease.

Thyroid cancer has a long history of being treated with radiopharmaceuticals: for nearly 70 years in people and almost 50 years in dogs. That shared history forms the basis for what’s known as comparative oncology — a field that studies naturally occurring cancers in pets to inform how similar diseases are treated in humans.

“Mizzou’s unique capabilities in radiopharmaceuticals — with direct access to the resources at MURR — allow for this comparative approach,” Maitz said. “Many of our clinical trials are designed to improve care for veterinary patients, but they can also give us an insight that can help advance human medicine.”

Using MURR’s specialized facilities and Mizzou’s collaborative research environment and combining expertise in chemistry, small animal studies, imaging and new drug design, Maitz hopes these resources can help build a domestic pipeline for radiopharmaceutical development.

“We want to use these naturally occurring cases to better inform which radiopharmaceuticals we develop and how we design them,” Maitz said. “By using advanced imaging to track where the radioactivity goes, modeling the dose delivered and predicting the biological effect, we can design better treatments for pets — and ultimately, for people.”

The study, “Prognostic role of patient, tumour and radiomic factors influencing outcomes in dogs with thyroid cancer treated with Iodine-131,” was published in the journal Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. Co-authors are Caitlin Cowan and Lindsay Donnelly at Mizzou; Ibrahim Chamseddine, Jan Schuemann and Alejandro Bertolet at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School; and Rebecca J. Abergel at University of California, Berkley.