By Eric Stann

April 9, 2025

Contact: Eric Stann, StannE@missouri.edu

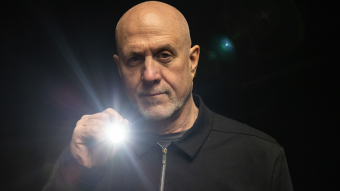

The universe doesn’t come with an instruction manual — but if it did, University of Missouri Assistant Professor Charles Steinhardt suspects a few pages are missing. Either the universe has been playing by different rules all along, or humanity has been reading the script wrong.

Traditionally, astronomers have grouped galaxies into two different categories: blue, which are young and actively forming stars, and red, which are older and have ceased star formation. Now, Steinhardt is challenging the traditional understanding of galaxies by proposing a third category: red star-forming. They don’t fit neatly into the usual blue or red — instead, they’re somewhere in between.

“Red star-forming galaxies primarily produce low-mass stars, making them appear red despite ongoing star birth,” he said. “This theory was developed to address inconsistencies with the traditional observed ratios of black hole mass to stellar mass and the differing initial mass functions in blue and red galaxies — two problems not explainable by aging or merging alone. However, what we learned is that most of the stars we see today might have formed under different conditions than we previously believed.”

Steinhardt’s research suggests that red star-forming galaxies might have played a much bigger role in the universe’s history. This could change our current understanding of how galaxies evolve, the processes that shape them and how we measure star formation throughout the universe's history.

“The existence of these galaxies could mean that the universe has formed significantly more stars than previously estimated,” he said. “It supports the idea that the life cycle of galaxies is more complex than a simple progression from blue to red and dead.”

A new take on post-starburst galaxies

Traditionally, galaxies are known to have evolved either through gradual aging or by merging, where the collisions can trigger bursts of new stars. Therefore, astronomers have long been puzzled by post-starburst galaxies, which suddenly stop making new stars after a short period of intense star formation. The common theory is that two galaxies collide, causing a quick burst of new stars before running out of energy and going quiet.

But Steinhardt suggests another possibility. Some of these galaxies may have been slowly forming small, red stars instead of experiencing a sudden burst of star formation. If that’s true, he said, we may need to change how we define post-starburst galaxies, as some might belong to a different category of red star-forming galaxies.

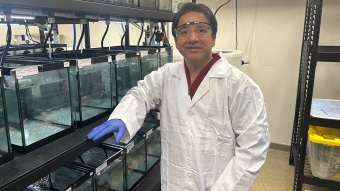

In the future, Steinhardt and his students in Mizzou’s Department of Physics plan on conducting more advanced tests to further investigate star-forming galaxies. Junior Mathieux Harper and a team of undergraduate students will look for more evidence to support the idea that some post-starburst galaxies fall into the newly proposed category. Meanwhile, sophomores Carter Meyerhoff and Zach Borowiak will lead a research project using data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite to study over two billion stars in the Milky Way.

“Do Red Galaxies Form More Stars Than Blue Galaxies?” was published in the Astrophysical Journal.