August 13, 2025

Contact: Brian Consiglio, consigliob@missouri.edu

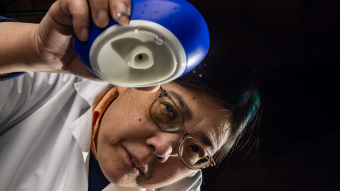

A team of researchers at the University of Missouri is on a mission to better understand which immune cells in pigs are most responsive to an influenza infection.

Because swine and humans share genetic similarities, their research may one day lay the groundwork for improved therapies or vaccines to protect both pigs and humans against influenza, which has major implications for the pork industry and human health.

“While pigs and humans are very similar at the cellular level, they are not identical,” John Driver, an associate professor in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, said. “A better understanding of how the immune system of pigs responds to influenza infection and how that immune response may differ in humans opens up a new world of potential for improved therapies and vaccines for both species.”

Despite T cells and B cells in the immune system having millions of different receptors that recognize and respond to various viruses, only a tiny fraction of these cells have the right receptors to recognize the always-evolving influenza virus.

So, in a recent study, Driver and his team sought to identify which immune cells in pigs have receptors that are most reactive to influenza. They accomplished this by customizing a technology called single-cell RNA sequencing for pigs. This powerful tool is used by scientists to learn more about how a body’s cells operate at a highly detailed level, including cells of the immune system.

“By better identifying which B and T cells are more likely to recognize an influenza infection, that knowledge may help those who are trying to develop improved therapies or vaccines,” Driver, a principal investigator in the Bond Life Sciences Center, said. “Influenza viruses mutate rapidly, which is why we must get a new flu vaccine each year. But if we can one day find which cell receptors bind to parts of the influenza virus that don’t change, that may be the key to improved vaccines that give us immunity for much longer.”

Influenza in both animals and humans is widely considered to be at the top of the list of viruses that could cause a pandemic. Avian influenza has recently affected the poultry industry and raised egg prices at grocery stores. There is great concern that bird flu will spread from birds to pigs and humans as well.

“If we can find an effective flu vaccine or therapy for pigs, that would be huge for the swine industry and reduce the potential for a future pandemic,” Driver said. “In 2009, the H1N1 virus that caused the swine flu pandemic was a combination of viruses from pigs, birds and humans that mixed together to produce a new virus that that our bodies were totally unprepared for.”

Mizzou is the perfect place for Driver’s impactful research. The National Swine Resource and Research Center, the new NextGen Center for Influenza and Emerging Infectious Diseases, and the Genomics Technology Core are all on the same campus, supporting Driver’s scientific discoveries.

“The interdisciplinary collaboration at Mizzou allows us to tackle one of society’s biggest infectious disease challenges,” Driver said. “I get to work with fantastic investigators who are doing cutting-edge research. The discoveries we make today can lead to major improvements in both animal and human health down the road.”

“Single-cell antigen receptor sequencing in pigs with influenza” was published in Communications Biology.