June 3, 2024

Contact: Courtney Perrett, 573-882-6217, cperrett@missouri.edu

Photos by Ben Stewart

Growing up in the heart of Michigan, Kathryn Moss was enraptured by science in early elementary school. From propagating plants to performing dissections, Moss was captivated by the inner workings of a cell. Later on in her childhood, when she was diagnosed with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) — a rare inherited genetic disease that causes peripheral nerve damage, muscle loss and weakness in the lower limbs — her love for science acted as both a comfort and the guiding force of her burgeoning career.

During high school, Moss began to realize that she could use her passion for cells as well as her personal experience as a CMT patient to focus her career on helping people who experience similar limitations from the disease.

Taking inspiration from her lived experience with CMT1A, the form of CMT she experiences, Moss set out to become a neuroscience researcher — historically one of the most challenging qualifications in biomedical research. First, she attended the University of Michigan, where she became immersed in undergraduate research and cellular and molecular biology. After receiving her doctorate from Emory University and completing a postdoctoral fellowship at Johns Hopkins University, Moss became what she’d always dreamed of: a neuroscientist studying CMT.

And now, another dream is coming true: Moss is joining the University of Missouri’s leading neuroscience team at NextGen Precision Health, where she’ll work alongside a team of visionary researchers like Smita Saxena and W. David Arnold. She will serve as an assistant professor in the School of Medicine’s Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation department.

“I think it's wonderful that there is a growing neuromuscular research community at the University of Missouri,” Moss said. “My goal is to improve the lives of CMT patients in Missouri, across the country and throughout the world — a goal that will be supported by the expertise and environment at Mizzou. I think I'm going to fit in perfectly.”

Patients of CMT experience a range of symptoms, including muscle weakness and loss, usually beginning in the feet and lower legs and often progressing to the hands. Sensory abnormalities including numbness and neuropathic pain such as tingling and burning sensations are also common. Moss hopes to bring relief to patients suffering with these symptoms with her research.

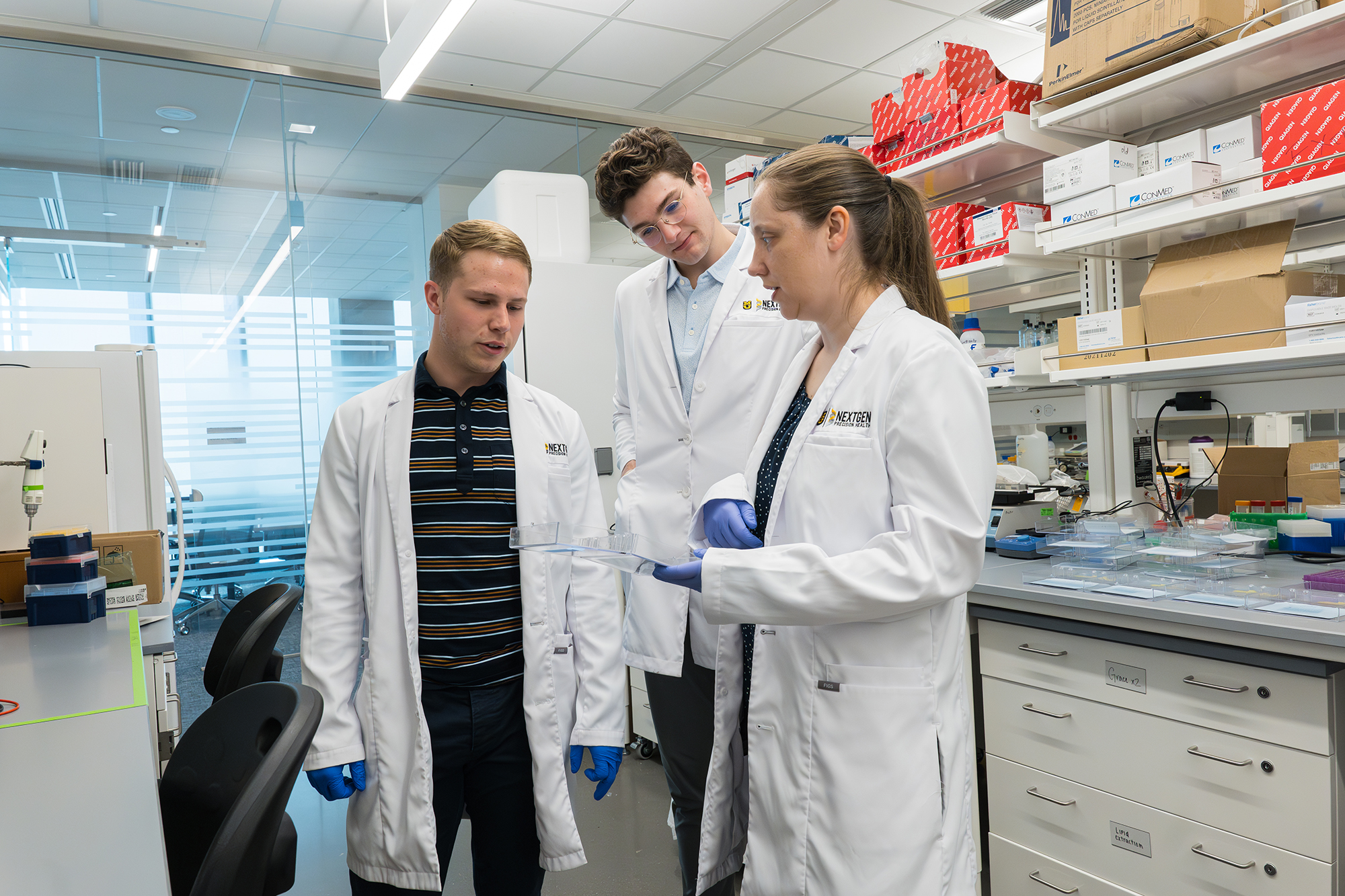

With the unbeatable resources of Mizzou’s NextGen Precision Health building and the might of one of the world’s great research universities, she is poised to help uncover a cure for CMT.

“With no current disease-modifying therapies for CMT, Dr. Moss’s work is crucial in understanding its mechanisms and developing much-needed treatments,” said W. David Arnold, the executive director of the NextGen Precision Health initiative. “Dr. Moss brings a dynamic and collaborative approach to our translational neuromuscular team, including my lab and those of Dr. Smita Saxena, Dr. Ryan Castoro and Dr. Kristina Kelly. The team boasts expertise ranging from the fundamental understanding of neuromuscular physiology to the application of the latest therapies for patients with neuromuscular diseases, and we look forward to the groundbreaking research Dr. Moss will undoubtedly contribute.”

Specifically, Moss hopes to examine the gene that is responsible for more than half of all CMT cases, including hers — peripheral myelin protein 22, or PMP22. Her goal is to understand the role of the gene and its encoded protein in supporting the transmission of electrical signals along nerve axons, which enable people to move their muscles and sense their environment. By understanding how PMP22 operates, Moss hopes to unlock a way to treat the disease by restoring appropriate transmission of electrical signals in CMT patients.

Unraveling the science

Even though CMT is classified as a rare disease, it is estimated to affect at least one in 2,500 people, making it relatively common among rare diseases. While CMT is considered underdiagnosed, it’s often misdiagnosed and left untreated.

“CMT is really an umbrella term for a lot of diseases,” Moss said. “PMP22 is unique, though, because it represents more than half of all CMT cases, and this gene can be mutated in multiple ways to cause CMT. The disease is relatively common, but not very well-known, possibly due to an underappreciation for how debilitating the symptoms can be.”

In her inquiry of PMP22, Moss hopes to discover the function of PMP22 protein in healthy myelin and how this function is changed in CMT. Understanding this basic biology will provide clues about processes going wrong in the disease and identify possible candidates for developing treatments.

Building upon traditions, nurturing solutions

CMT’s most widespread forms are autosomal dominant, which means that if one parent has the disease, that person’s child would have a 50% chance of inheriting an illness that currently has no cure.

“The only treatments that are currently available are assistive devices, for example braces and orthotics to help with gait issues,” Moss said. “And for people that experience neuropathic pain, there's just pain medicine, but that doesn’t get to the root of the problem. One of my main goals is to raise awareness and create an appreciation of the problem because CMT is so understudied.”

Moss believes NextGen Precision Health can help her reach her goals. She specifically highlighted NextGen’s dedication to academic medicine — the practice of bench-to-bedside translation — and the program’s interdisciplinary collaborations with scientists in veterinary medicine as well as physicians.

“Mizzou has all the necessary expertise and resources available for doing challenging studies that push the envelope,” Moss said. “I feel that I’ll be able to make my work translational here and, eventually, make it into clinical trials and help patients.”