Published on Show Me Mizzou Jan. 10, 2024

Story by Nina Mukerjee Furstenau, BJ ’84

Photos by Abbie Lankitus

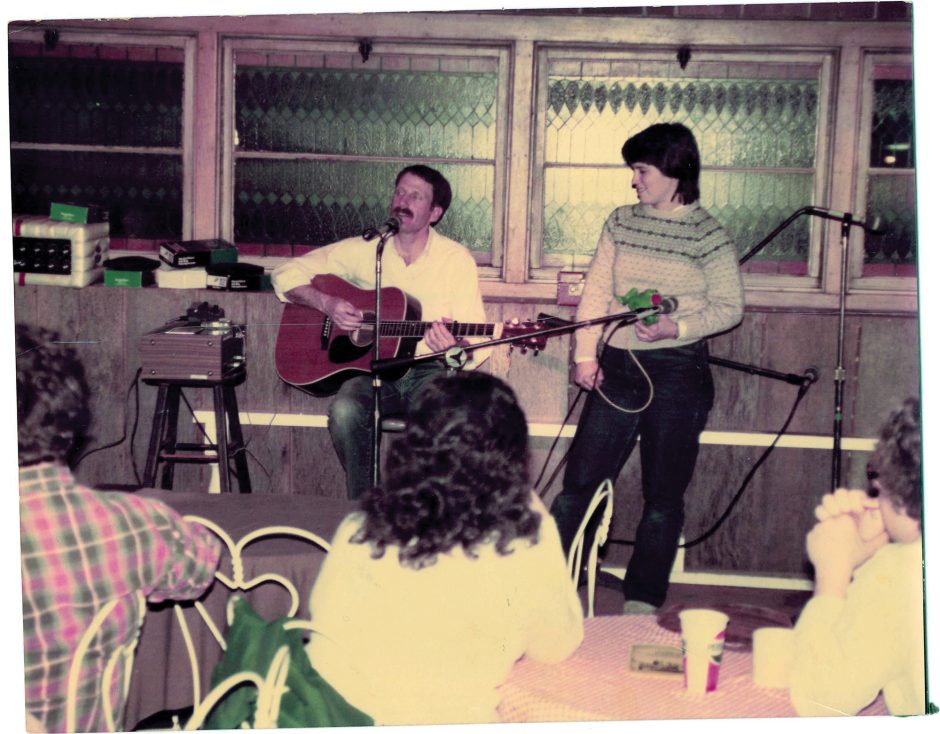

The Chez Chandelle Coffeehouse on Hitt Street began offering coffee and music in 1964 in the Presbyterian student center, now part of the First Presbyterian Church. For more than 30 years, its coffee-and-folk-music culture developed around bistro tables in a basement room.

Lighting was dim, but that didn’t dispel the air of anticipation, especially on open mic nights. In its heyday, the Chez was cooperatively managed by eight university students who kept the coffee shop open seven nights a week in exchange for room and board.

By then, coffee, “the cup that cheers but not inebriates,” was thought to be the “indispensable beverage of strong nations” and the “drink of democracy,” according to All About Coffee, a 1922 book published by the Tea and Coffee Trade Journal. Its editor, William H. Ukers, bestowed coffee with other mantles: “the thought-inspiring beverage from Arabia,” “the marvelous berry” and the “invigorating drink which drives sad care from the heart” among them.

During its prime, the culture at the Chez involved some combination of folk music, bellbottoms, John Lennon-approved Gitanes cigarettes and earnest open mic nights. Beloved locally, it was also recognized by the wider world when, in 1969, the National Coffee House Conference in New York named the Chez one of its five outstanding American coffeehouses. Aside from diners and gas stations, it was among the only spots outside home kitchens to get your morning coffee in Columbia.

More than 50 years and billions of dollars later, coffee is a way of life. In Columbia today, patrons can pick from Acola Coffee Co., the Grind, Starbucks, Love Coffee, Lakota, Scooters, Fretboard, Kaldi’s, Shortwave, Toasty Goat, Vida and more. Want the diner variety? A cup of Ernie’s java is still there for you. The many options have transformed the city’s coffee culture. Although houses such as the Chez are no longer, the aim remains the same: providing comfort, opportunity and caffeine for all.

The Marvelous Berry

Coffee as a drink is believed to have been discovered in Ethiopia by Kaldi, a herdsman. Although competing narratives abound, Kaldi, it’s said, found his goats dancing and leaping after nibbling on the marvelous berry. After that, with something approximating a leap, the intriguing drink crossed oceans and land routes to arrive in cups across the globe.

Early American settlers, though, were partial to tea (with a tip of the hat to the British). The 1773 Boston Tea Party, which occurred in response to issues surrounding the leaf’s sourcing and taxation, forever altered attitudes and trade routes. When Boston rebels dumped (mostly Chinese) black tea being imported by the British East India Co., merchants and distributors began shipping the leaf directly from the source.

Tea was an important enough commodity that, though expensive, travelers to the western frontier as early as 1810 packed it. In 1831, a pound of tea cost $1 — the same as 5 pounds of coffee, according to Robert Hellyer in his 2021 book Green with Milk and Sugar: When Japan Filled America’s Tea Cups. As the so-called Gateway to the West, St. Louis stocked heavy for these westward travelers.

“Coffee’s early availability in St. Louis could be tied to one factor — location,” says Katie Moon of the Missouri Historical Society. The city’s spot on the Mississippi, which would become one of the country’s major shipping routes, enabled steamboats from New Orleans as early as 1817 to push coffee north. In the 1850s, hundreds of riverboats were making stops at St. Louis docks. Coffee had become a staple.

For a while, St. Louis was the largest inland coffee distribution hub in the world. In 1845, its 35,000 residents had a choice of 50-plus coffee shops. It was clear that Missouri was all in for the bean.

Vanilla Lattes and Blend 700

The number of coffee drinks ordered in 45 minutes one morning at Kaldi’s Coffee in Cornell Hall revealed students ingesting nearly 200 liquid ounces of the world’s favorite as they studied in nearby chairs, scrolled on their phones or went to class, barely breaking stride.

“Vanilla lattes are probably the most popular,” a student barista says while steam hisses from the espresso machine, adding that she’s “using Blend 700 right now.”

Howard Lerner and Suzanne Langlois founded St. Louis-based Kaldi’s in 1994. A decade later, Josh Ferguson, BS ’03, and Tricia Zimmer Ferguson, BS BA ’03, invested to become business partners. In 2007, the couple and Tyler Zimmer, BS ’08, (Tricia’s brother) bought the rest of the company. Kaldi’s has since introduced canned cold brew in groceries and, after acquiring Firepot teas, is expanding further into that sector. Currently, the company has 11 locations in St. Louis, four in Atlanta and two in Columbia — at Cornell Hall and inside a local Schnucks location.

Trips to coffee-producing countries and frequent cuppings (tastings) are central to developing Kaldi’s blends. Company values extend to how beans are purchased, says Louis Nahlik, brand manager at Kaldi’s, and they often enjoy direct relationships with the farmers who cultivate their beans.

Unlike the vanilla latte boom at Cornell Hall, the trend in specialty coffee is based more on the freshness of the coffee, not syrups. Dale Bassham, Kaldi’s roaster in St. Louis and former owner of Shortwave Coffee in Columbia, compares it to a tomato. “You can get a tomato at the grocery store all year long, but if you get it when it’s really fresh — that’s what a tomato should taste like.”

Kaldi’s roasting facility in St. Louis is located just east of Forest Park beneath the I-64 corridor. The scent of roasted coffee not only fills the facility, but sometimes commuters are also treated to wafts of it as they drive on the highway above. On a recent day, Bassham works with one of the older machines, a 1937 German roaster, and stops to explain that the raw coffee is heated to 403 degrees. “It’s about to get real loud in here,” he says. Steam erupts as beans slide into a cooling tray, bringing down the temperature to 72 degrees in 3 minutes. After roasting, the fragrance, aroma, flavor and aftertaste are scored.

The Kaldi’s connection with Mizzou extends into the classroom. Using a coffee shop business simulator, students in the Trulaske College of Business can input data on pricing, profit margins, productivity and other trackable data to see the effects on the shop’s bottom line.

“I wish they would have had something like this when I was in school,” says Zimmer Ferguson. Her likeness is featured in the simulator software. She calls it “pretty cool that we have evolved to using technology like this that can be applied to real-life learning. I like this structure, as it can be applied to many business applications.” It made sense to connect MU students with the wider coffee world for Zimmer Ferguson. She describes “lifelong connections to this university,” adding, “I look forward to carrying forward that relationship for years to come.”

Columbia’s enduring coffee shop, Lakota, is managed by co-owner Andrew DuCharme, BS ’09, and now has three locations — downtown, on Green Meadows and on the University Hospital campus.

“We are the longest-standing coffee shop in Columbia,” says DuCharme, adding that when his dad, Skip, opened the shop in 1992, “if you wanted a cup of coffee, you had to go to a diner.” Lakota roasts between 2,000 to 4,000 pounds of coffee a week, depending on business. DuCharme’s brother, Jon, does the roasting, 25 pounds at a time.

Lakota’s Ninth Street shop is abuzz on a recent afternoon, which is typical given its role as a community hub: Toward the front, a few small groups talk while students with open laptops occupy the back. Baristas pass cold brew orders over the counter at a good clip. A 2023 remodel has added a contemporary vibrancy to its familiar aesthetic.

The company sources most of its beans from trusted importers. In early autumn, Lakota was awaiting the arrival of beans from Costa Rica, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Sumatra and Colombia. DuCharme’s an espresso drinker. His favorite region? “Nicaragua beans have a chocolate undertone that is natural that I really like.”

Riding the Third Wave

American coffee history is divided into three waves. The so-called first wave was imported pre-roasted, ground and packaged. The second wave hit the U.S. in the late 1960s when Dutch immigrant Alfred Peet began roasting high-quality beans in small batches and infusing European style into his Berkeley, California, coffee shop. With the early 1970s rise of Starbucks, coffee knowledge spread. Suddenly, Americans were ordering grande and vente cappuccinos and lattes.

“Third-wave coffee is relatively new,” says Brian Ott, a visiting assistant professor of sociology in the College of Arts and Science, who calls it “the market segment of connoisseurs.” Ott researches the sociology of work and the social components of how we learn to taste. He prefers a morning cortado, a drink originally from Spain that’s equal parts espresso and milk that he gets from third-wave shop Acola on Tenth Street.

“Historically, coffee has been this beverage that’s widely accessible,” Ott says. “But now in coffee shop culture, they are not only talking about country of origin for the beans but of specific farms. They are providing information on altitude and soil types that you might see with wine. They introduce ideas of tasting notes.”

Refined coffee expertise may seem new, but early in its history, Missouri was a U.S. coffee influencer. The state can thank the French for that. As part of the Louisiana Territory, the region was greatly shaped by French settlers, themselves early adopters of coffee from Arabia. Paris had some 1,800 cafes around the time St. Louis was founded, according to the coffee magazine Standart. French Missourians brought that taste of home with them, says Moon of the Missouri Historical Society. Even the 1803 sale of the territory to the United States didn’t stop the flow.

More than 200 years later, coffee drinks have evolved. Shops make each cup to order — think a pour-over with a focus on a single bean source. “The third wave distinguishes itself by saying coffee is the centerpiece,” Ott says. “They might say, ‘If you order a mocha, you’re not really into coffee; you’re into chocolate.’”

Industries that focus on taste expertise tend to develop more refined methods for identifying and talking about their products, he notes. “Setting itself up as ‘the third wave’ is establishing itself as something different. It’s a way of creating boundaries.” Knowledgeable baristas are another focus of the third-wave evolution.

Back in the Chez heyday, coffee was on the cusp of revolution, and the shop culture made an impact. “I hear people talk about the Chez all the time,” says Nancy Thomas, First Presbyterian Church member and vice president and senior registrar of the Boone County Historical Society. Her recent church project to organize and preserve materials on the Chez, which shuttered as an ongoing concern in 1999, unearthed menus from the 1980s, newspaper clippings describing the rich community of folk musicians and photos of a capacity crowd relaxing and listening to live music just feet away.

Even then, coffee concoctions were part of the draw. Various menus offered 17 types of coffee and tea, ranging from the Jamaican — coffee made with 1 teaspoon sugar, 1/2 a cinnamon stick, 1 clove, 1 drop orange extract and 1 drop rum flavoring — to Café Borgia, made with 1 teaspoon instant milk, 1 teaspoon chocolate syrup, 1/2 cup hot water, 1 drop orange extract and a sprinkle of cinnamon.

Decades — and millions of pumpkin spice lattes — later, coffee culture has matured in ways once unimaginable. So much so, in fact, that a current trend is currently making inroads: Tea in its myriad forms has become a feature of coffee shops everywhere — including Kaldi’s and Lakota. It’s a faint — but discernable — historical ricochet.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.