Oct. 19, 2022

Contact: Eric Stann, 573-882-3346, StannE@missouri.edu

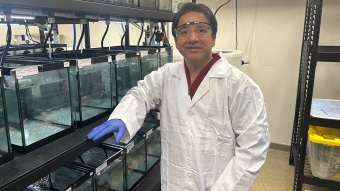

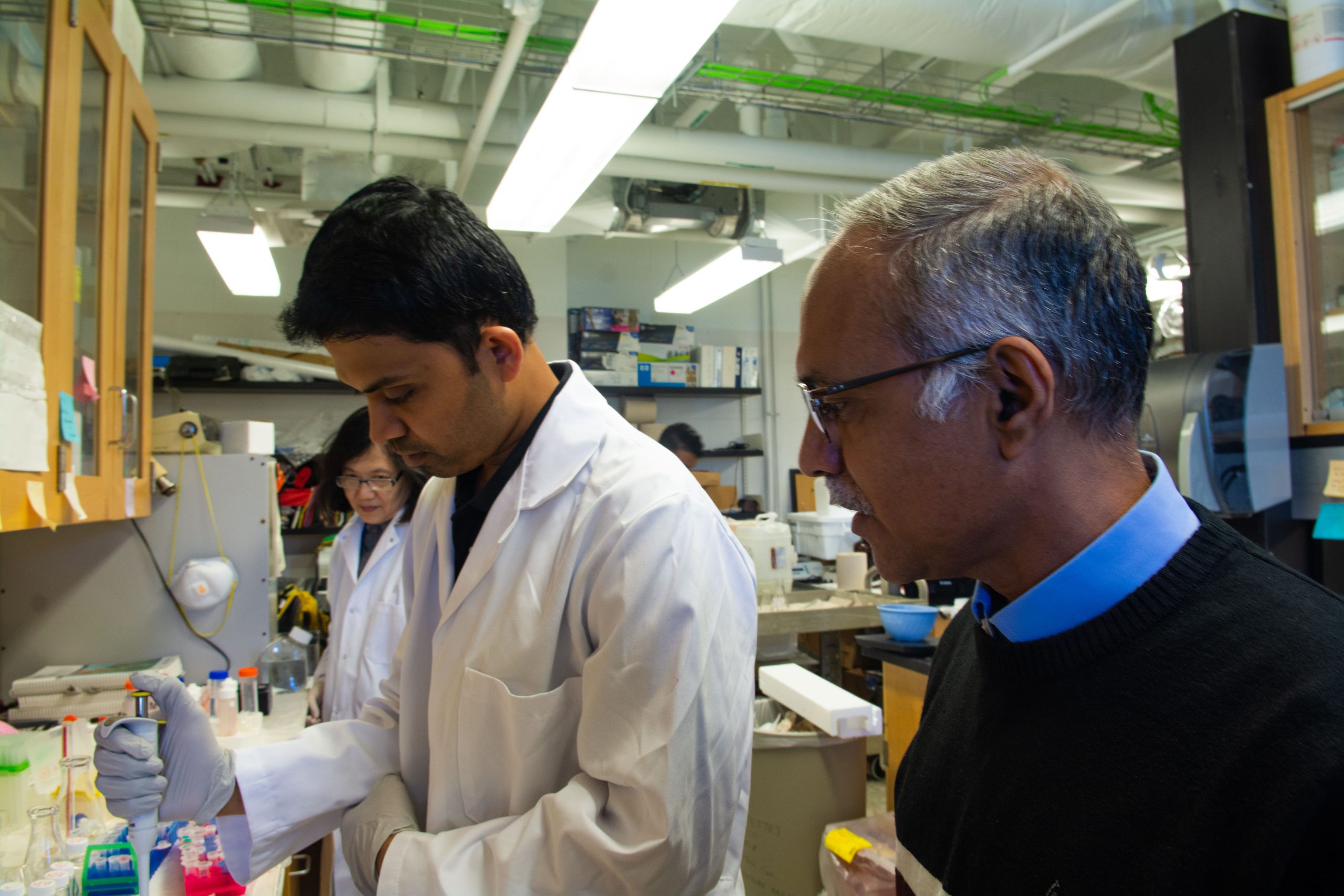

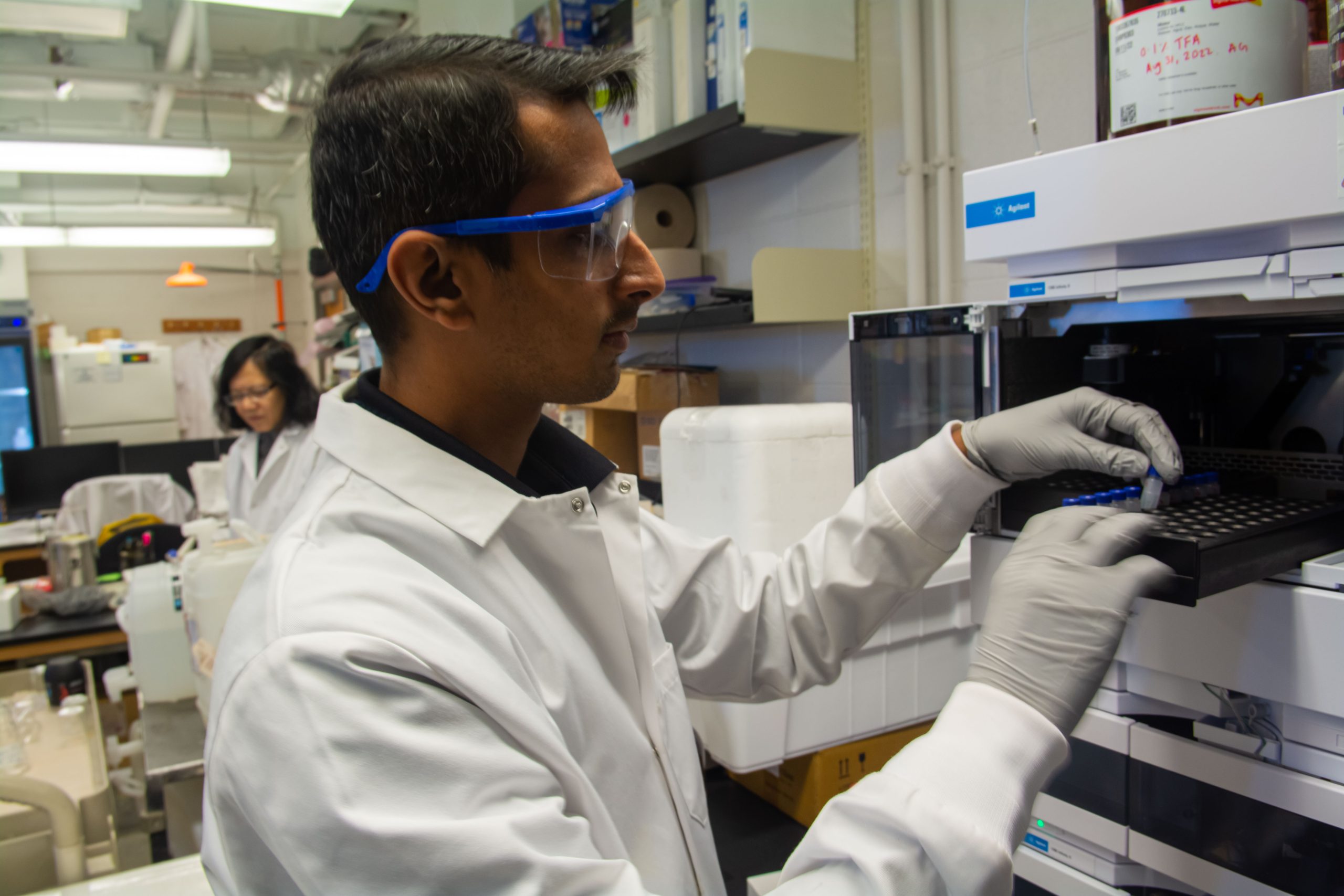

When someone is diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer — one of two main forms of lung cancer — there is a 70-80% chance that after 14 months the cancer will develop a resistance to the drug therapy originally given to fight it. If that happens, there aren’t many treatment options currently available. That’s why Raghuraman Kannan, the Michael J. and Sharon R. Bukstein Chair in Cancer Research in the University of Missouri School of Medicine, is determined to find a solution.

“We want to find out why patients are becoming resistant to the therapeutic agent and determine how we can help them overcome that challenge,” he said.

Kannan and a team of researchers recently received a $2.35 million grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to generate preclinical data based on their existing research — the required step before human clinical trials can begin. Previously, the team identified two genes involved in the development of this drug resistance. Now, with the help of this grant, researchers will be able to test the approach they developed to prevent resistance.

Kannan said their approach combines a biological process called RNA interference (RNAi) with protein-based nanoparticles. The nanoparticles will help safely deliver the RNA to the cancer tumor and cause the resistance to stop. This, in turn, will allow the cancer to be more responsive to the efforts of the original drug therapy.

“Through RNAi, we have something called a silencing RNA (siRNA),” he said. “As the name suggests, it silences the gene of interest, which in this case are the two genes causing this drug resistance. But siRNAs are inherently unstable in blood. So, we must develop a technology to deliver this siRNA to the [cancer] tumor. That’s where the nanoparticle comes in.”

Kannan has created similar nanoparticle-based drug delivery methods to develop treatments for ovarian, breast, pancreatic and liver cancers. He has written more than 55 papers and holds seven patents. He said his ultimate goal is to make his work more accessible, so doctors can use it to help more patients.

“Toward Translation of MU-CN29: New Therapeutic Nanoparticle for Drug Resistant NSCLC,” was awarded by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA274677-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Editor’s note:

Kannan has a joint appointment in the Department of Biomedical, Biological and Chemical Engineering in the MU College of Engineering.