Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 16, 2022

Story by Marcus Wilkins, BA ’03 / Photos by Abbie Lankitus / Video by Mizzou Visual Productions

Illustrations by Violet Frances, Bryan Christie Design

Stroll past Damon Coyle’s workspace on any given weekday and you might feel as if you’ve stumbled upon a special effects lab.

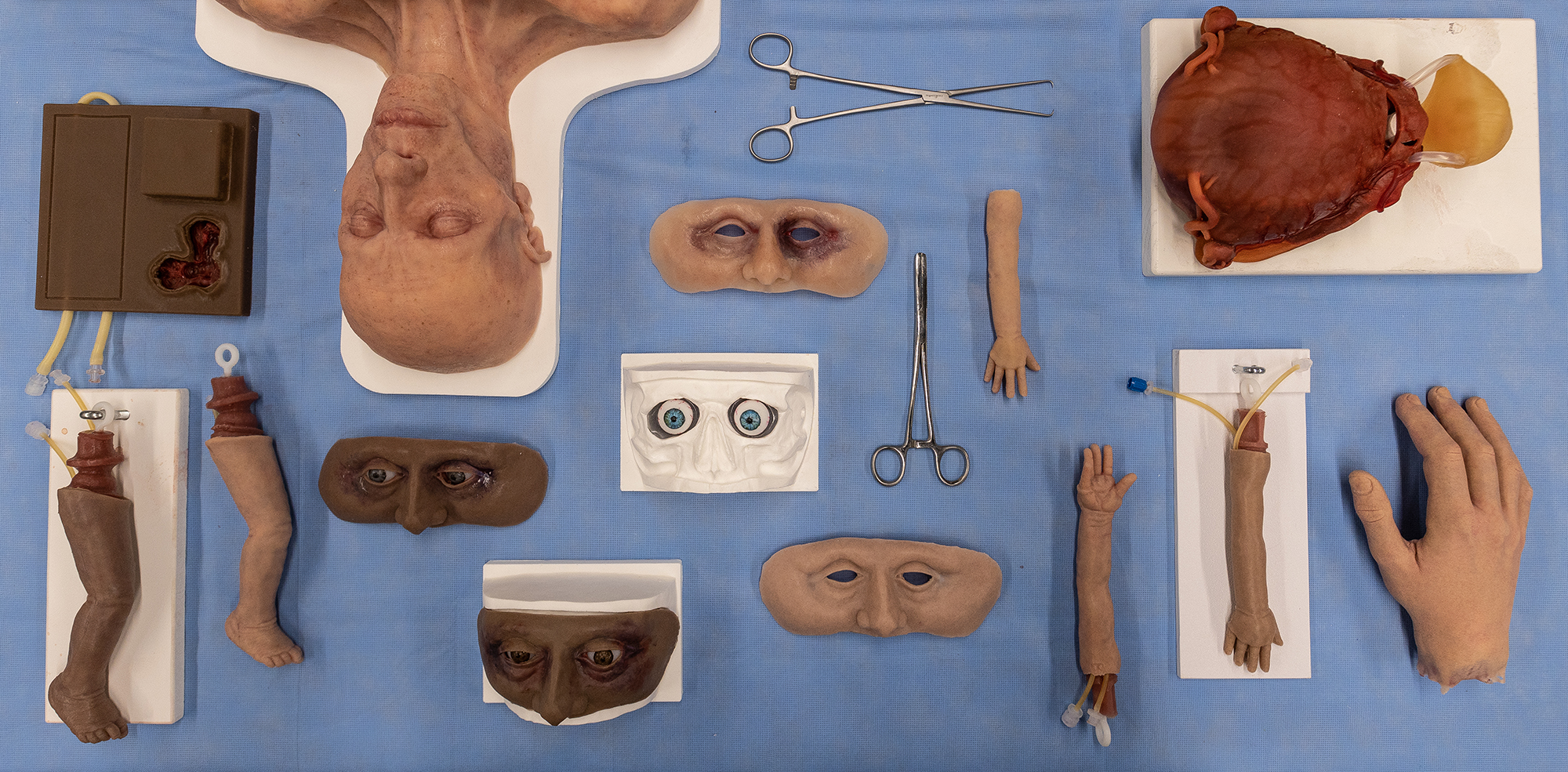

What appear to be glistening crimson organs rest in metal procedure trays and plastic medical tubs. Suture scissors and thumb forceps surround swatches of wounded and partially stitched skin. Tubes of mysterious fluids crawl across blue surgical cloth. Gray cadaver torsos cast elongated shadows, while dislodged fake eyeballs gawk skeptically this way and that.

Although creepy at first glance, the body parts aren’t real. This windowless fourth-floor Mizzou studio houses a singular medical innovation specialist. Part artist, part physician — with a dash of fun-loving mad scientist — Coyle, BS, ’11, creates strikingly lifelike training devices at the Innovation Lab in MU’s Russell D. and Mary B. Shelden Clinical Simulation Center.

The realistic “trainers,” made mostly of latex and silicone compounds that mimic with remarkable accuracy human and animal tissue, are used by students learning clinical procedures in the worlds of health care and veterinary medicine.

As Coyle holds up and rotates an arm to display its surface, a smile of satisfaction cuts across his bearded face as he describes the ability to “intrinsically change the pigmentation of the silicone” that he casts in his studio. “I can make any skin tone,” he says. “I also use what’s called ‘flocking’ — very small hairs or fibers of varying colors that you can put in at the mixing stage.”

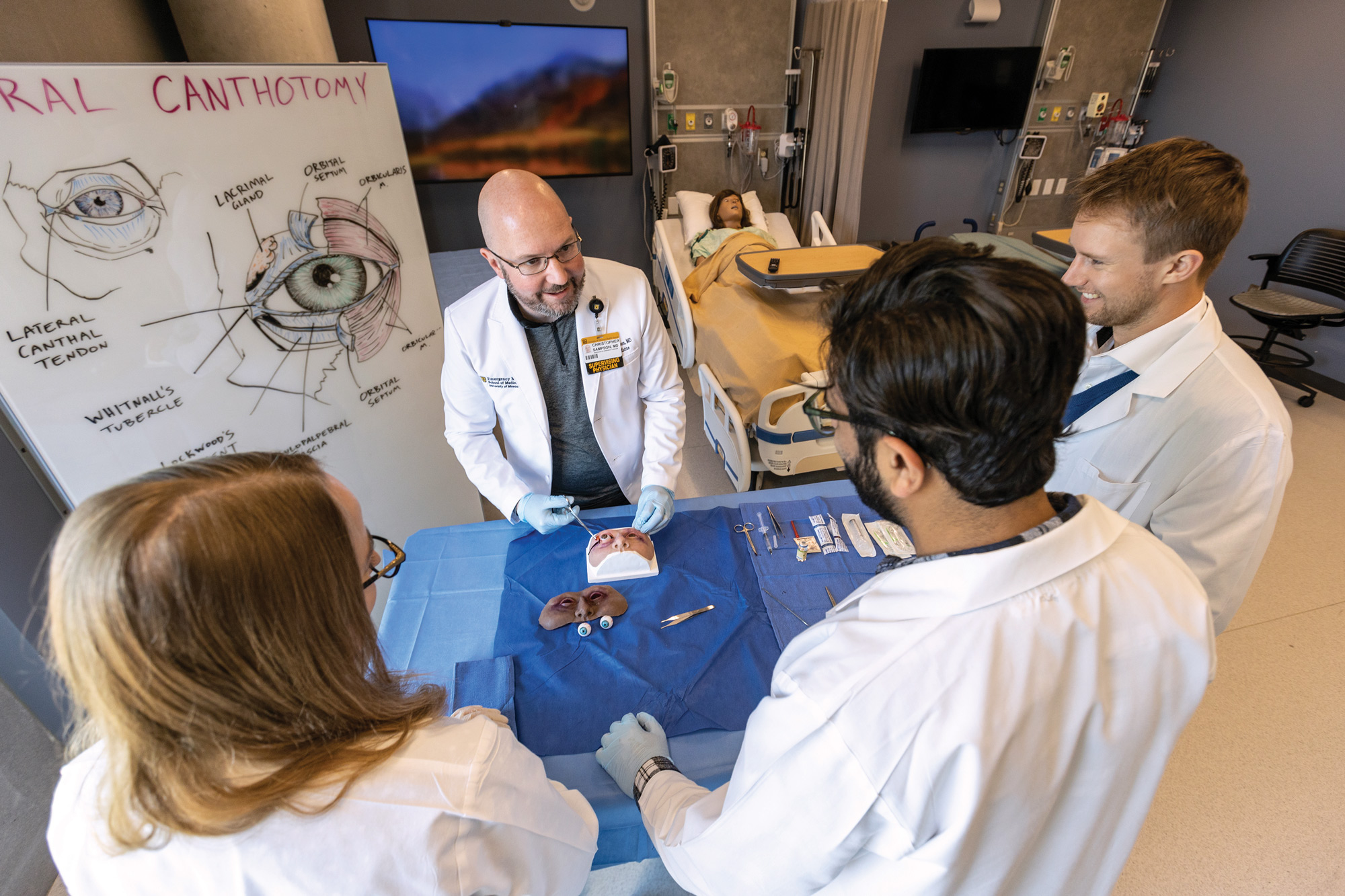

Coyle’s catalog of handmade creations features hundreds of human appendages and more than 20 refined prototypes. He’s designed a neonatal intravenous trainer fitted with arterial tubing for nurses to practice inserting needles into the tiny arms and legs of newborns. The ocular trauma kit is an eye mask-shaped section of face featuring removable eyes for easy cleaning. And the multipurpose nursing skills pad allows trainees to refine their injection, intravenous starts and wound-care skills on a square of self-healing “flesh.”

“We started the Innovations Lab in 2019 because there’s a gap in the market for how the realistic task trainers look, feel and react,” says Dena Higbee, executive director of simulation at the Shelden Center. “I knew Damon as a medical student, but I didn’t initially know that he had a background in sculpting. When I learned that, I thought, ‘This is ideal.’ ”

The opportunity was not only a perfect confluence of Coyle’s talent and experience but a chance to innovate in a job he could help define. And over time, he’s honed the definition.

“If I’m at a cocktail party or giving an elevator pitch, typically I tell people I’m a medical sculptor,” Coyle says. “I don’t dabble in anything. I tend to go all in with my attention, skills and energy.”

In the world of medical simulation, Coyle’s effects are as specialized as his job title. When tackling complex assignments, he has no similarly tasked innovation specialists to consult at other higher education institutions. “As far as we know, there’s no other clinical simulation center that has a dedicated lab to produce refined production pieces,” he says.

Were he to seek peers with whom to trade notes, they would likely be in Hollywood — with a key distinction: “With special effects work, the artists are creating for a very controlled environment, with precise lighting and often to be shown for only a handful of frames.”

Bodies of work

For a self-described introvert, Coyle is an affable and welcoming host. He flits among his displayed trainers, reaching for handmade body parts to best describe his methodology and process. He’s quick to laugh, naturally curious and eager to collaborate. That temperament, paired with Coyle’s imagination and know-how, make him uniquely suited to his craft.

If artistic acumen is inheritable, Coyle received it from his grandfather, a talented watercolor and pencil illustrator in the 1970s. Coyle and his two brothers grew up just outside Council Bluffs, Iowa, where his parents enthusiastically encouraged creativity. Someone was always sketching something, and papers constantly littered the bedroom floors.

“In my drawings, I liked to push realism and focus on figures,” Coyle recalls. “So, I decided to take a college-level anatomy course in high school to improve at rendering the superficial musculature.” Coyle and his parents still chuckle about the specificity of his boyhood career aspirations.

“I said I wanted to be a doctor artist.”

What seemed like a pretend occupation became real thanks in part to the breadth of educational experiences available at the University of Missouri. Coyle was an exceptional student fascinated by medical science, so an undergraduate biology degree en route to med school seemed like an obvious path. But he continued cultivating his creativity by taking art courses. Specifically, Coyle took a bronze sculpture class with Professor Emeritus James Calvin.

“Damon was quite skilled and interested in figuration and anatomy,” says Calvin, who penned a letter of recommendation for Coyle’s medical school application. “He was also committed to developing a wide-ranging skillset in terms of materials. One of the unique things about sculpture is that we’re not defined by a particular material; we’re defined by a discipline — which I’m sure has served him well.”

Coyle was three years into med school — through what many physicians consider the hardest part — when he had a realization.

“You have to throw a lot of hobbies aside to make room for the rigors of such a difficult education,” Coyle says. “I realized what brought me fulfillment at the end of the day was creating tangible items that somebody else can appreciate, touch, feel and use. Functional art, if you will. If my art could be used to help medical students, all the better.”

Enter Shelden Center Executive Director Higbee. With more than 20 years of experience in the field of medical simulation and 14 years at Mizzou, she was familiar with the limitations of some of those tangible items.

Higbee and Coyle began discussing the shortcomings of various task trainers used in the medical simulation community. Haptic authenticity (real feel), lifelike coloration, maintenance and durability would be paramount. There was also the matter of economics; Coyle could make replacement trainers and manikin parts at a fraction of the commercial cost. He now cranks out large batches of homemade suture training pads that outperform comparable products on the market.

“Our students are always going through a mental process and thinking, ‘This is just a piece of hard plastic, so if I put the needle in here, I know I’ll get [blood flow] return,’” Higbee says. “But if there’s no fidelity — if it doesn’t feel like a real patient — there’s limited transfer of knowledge. In the old days, we would practice putting IV needles in bananas, for goodness’ sake.”

Medical simulation has been around for as long as medical training. Ancient doctors taught anatomy on models built of clay, and in 18th-century France, students learned how to deliver babies on cloth birthing simulators. Today’s plastic simulation devices are a vast improvement — but Coyle knew he could do better.

He set up a makeshift lab on an old oak table in a spare bedroom at his house. Coyle’s first assignment was a uterus for a postpartum hemorrhage procedure, a project that required extensive trial and error to concoct the right rubber formula. It didn’t take long for Higbee to find dedicated lab space for Coyle.

“Surgery, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine — these are the disciplines in which simulation performs really well,” Higbee says. “So we started pursuing trainers for specific procedures within medical residency programs. And at the Shelden Center, we’re always trying to find ways to improve the simulation process.”

Simulation implementation

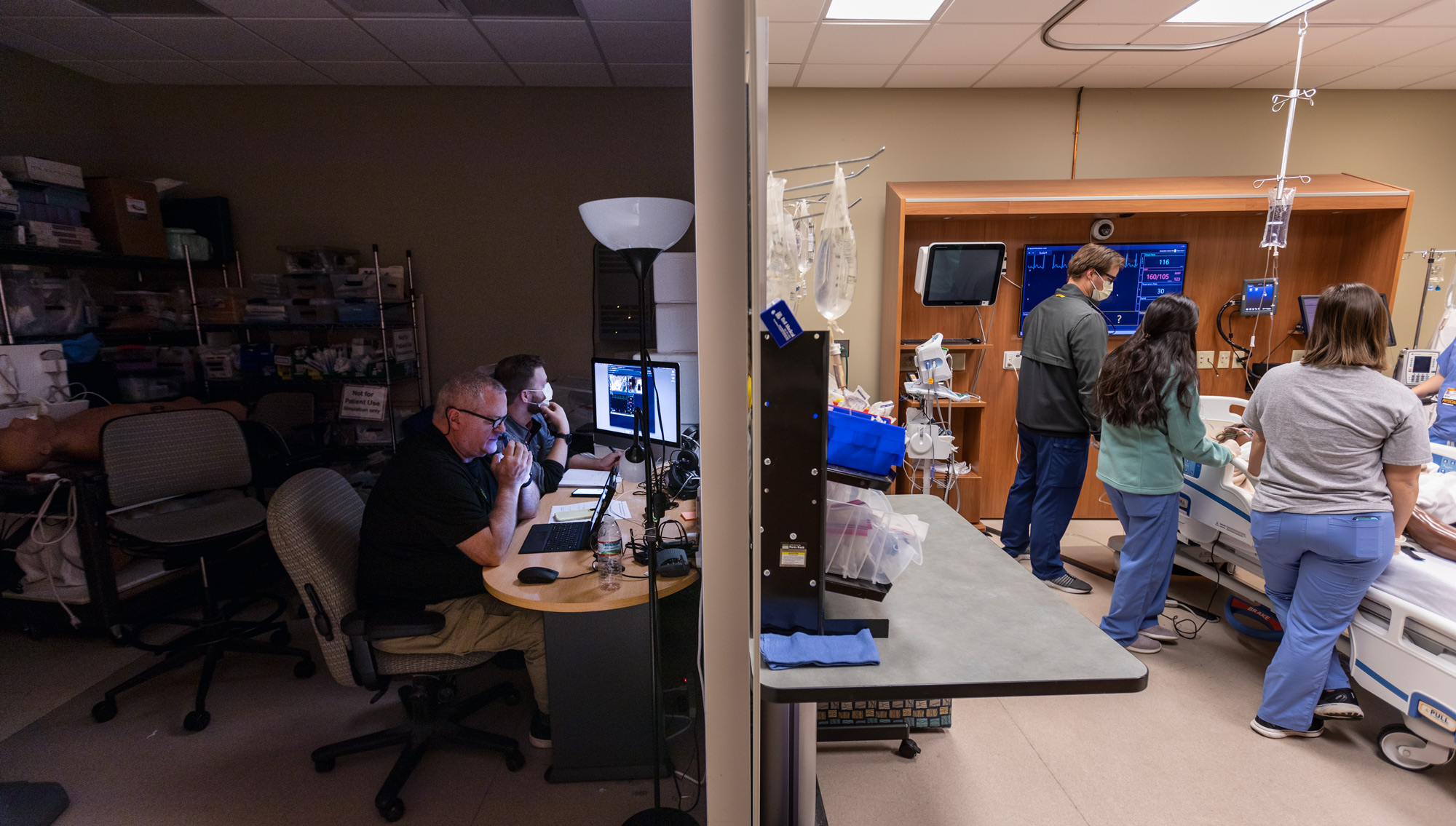

Hal was born ready for this. Comfortably reclined and swathed in a cotton gown, the patient seems to convey a stoic countenance, one betrayed by the occasional blink as surrounding medical students are briefed on his condition.

Aside from the mirrored glass opposite the door, the setting is a typical hospital room. Monitors, IV poles, respiratory outputs, crash carts and various instruments surround Hal. As the health care team members take their places and introduce themselves, the patient clears his throat and describes his plight.

“I think I just have the flu,” says a male voice emanating from a speaker on Hal’s bed. “But my wife said because I’ve been sick so long that I needed to come to the hospital.” He adds that he’s had severe nausea.

Hal is a patient-care training manikin — in this case, voiced by Marty Runyan, simulation education specialist. Capable of simulated breathing motion and other vital signs, Hal is part of an exercise that allows medical students to practice their bedside manner while adjusting to changing scenarios tweaked by Runyan and his team from behind the glass in the control room. It’s just one of hundreds of simulations carried out at the Shelden Center every semester.

Tim Koboldt is an assistant professor and simulation director of clinical emergency medicine. He says that this kind of training is critical to student success — and could save lives. “We often focus on what are called high-acuity, low-occurrence events,” he says. “These things are time-critical, where people need lifesaving interventions immediately. By doing these procedures in a lower-stress environment, with trainers and an opportunity to think through things, it gives medical students a chance to gain some muscle memory.”

Future doctors such as Chelsea Broomhead, a senior emergency medicine resident and a Medical Education and Simulation fellow at the School of Medicine, often face circumstances they’ve only read about.

“There’s a sweet spot when doing simulation,” Broomhead says. “If you’re completely overwhelmed by the scenario, you won’t remember anything. But if you’re unphased, you won’t remember, either. It’s also so important for the training devices to be realistic. Imagine trying to learn how to play trumpet on something that didn’t feel or act like a trumpet. Fidelity is critical.”

Thankfully, the Shelden Center — 25,000 combined square feet in the School of Medicine and the Patient-Centered Care Learning Center — houses thousands of high- and low-tech simulation devices, many of which work in concert with the trainers Coyle develops. For example, silicone specimens for tracheal (windpipe) or gastrostomy (abdomen) procedures can be attached to manikins such as Hal to increase the level of realism.

The centers feature 30 fully equipped examination rooms, 11 multipurpose simulation rooms, 12 observation and control rooms, and a Cerner hospital “room of the future” featuring the latest in cutting-edge technology. There is also the Mobile Sim unit, a 30-foot vehicle with four computerized patient manikins, virtual reality devices capable of simulating more than 110 medical scenarios and trained staff — all ready to deploy and instruct health care workers throughout the Show-Me State.

Specialist effects

One recent day in Coyle’s studio, detachable bellies, placentas, umbilical cords and craniums flank the artist’s coffee mug as he scrolls through detailed medical images online. Like the arresting parts and prosthetics displayed in his studio, Coyle’s passion for his work is impossible to ignore.

Take his canine spay surgical trainer. As he walks through an impromptu hands-on demonstration of how the cylindrical apparatus functions, he enthusiastically urges his visitors to test the realistic tension of the replaceable uteri.

“No assignment is ever typical, but when requests come to me from a department, usually they have been using a crude model or no model at all,” Coyle says. “That’s when I immediately get on the internet and watch procedural videos, or I’ll have the clinicians invite me to a procedure so I can get eyes on things and obtain as much research as possible into what the procedure actually entails.”

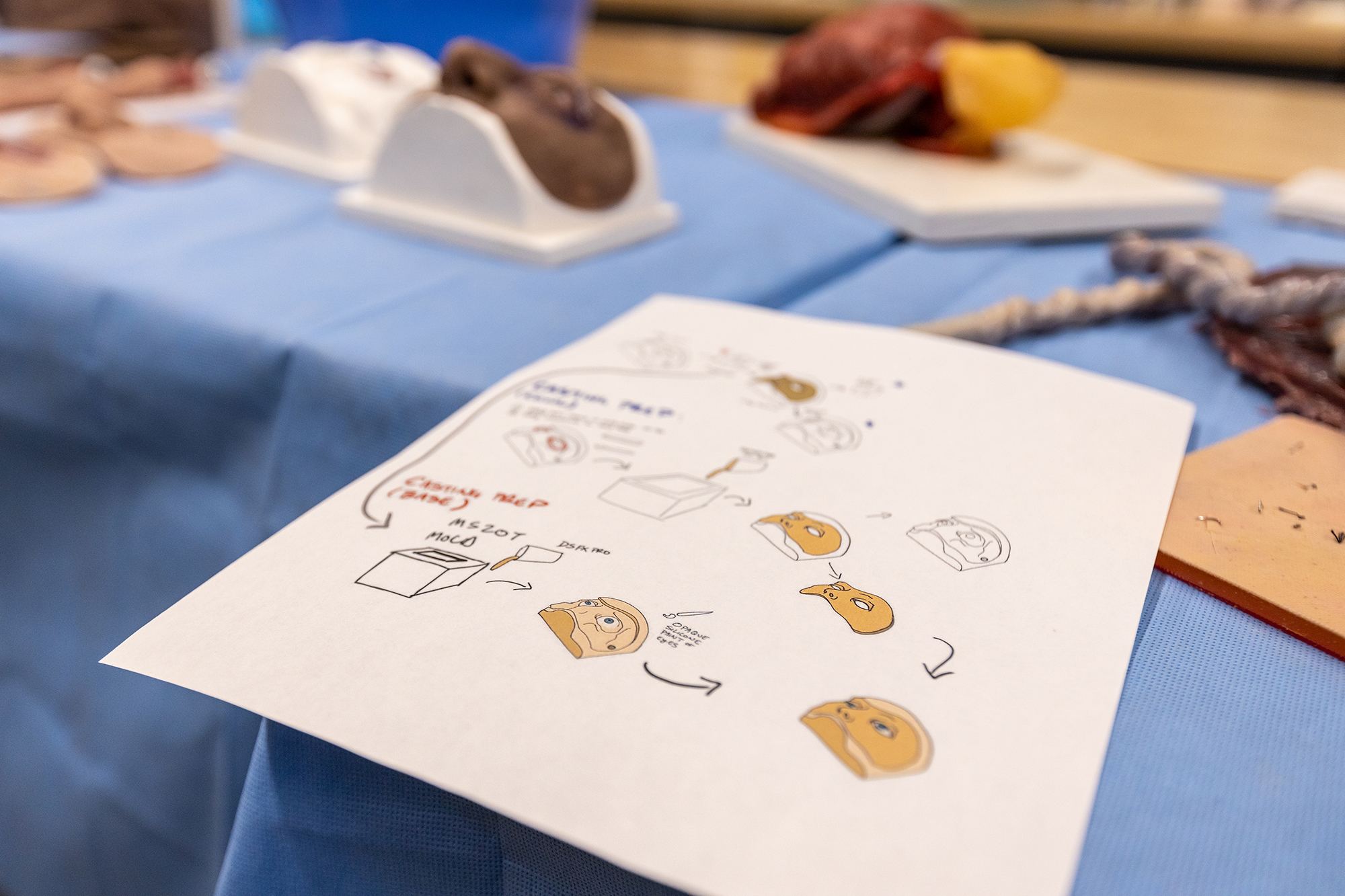

Coyle begins sketching the model — sometimes he does so on a digital pad, sometimes with paper and pencil — before sculpting with polymer-based “monster clay” named for its popularity in cinema. He prides himself on practicality, using everyday hardware products as building blocks for many of his creations (“I go to Menards a lot,” Coyle says). He has even used a mold of his wife’s arm and hand for an adult IV trainer used by a variety of health care students.

As Coyle’s reputation has grown, he and his colleagues have had to be more selective about assignments.

“Prioritizing Damon’s time comes down to who is the end user for a particular device,” Higbee says. “Is it a one-off? How many people can benefit from it? What products would work best for the curriculum, for residency training and hospital training?”

Coyle also places premiums on constructive criticism, trial and error, and nonstop tweaking. As the products are used and abused by trainees, he’s constantly adapting and improving his work.

“Typically, the biggest changes I make in the early stages relate to the softness of the tissues, and that’s a pretty easy fix,” Coyle says. “I have additives that can make our silicones softer or more rigid.”

Coyle draws from his well of medical knowledge daily, so it’s accurate to say he looks back — but never with regret. After all, this Mizzou-made “doctor artist” has realized the dream job he imagined more than 20 years ago.

Still, his approach to work suggests that were he practicing medicine today, no doubt he would be going all in — as he does in every endeavor.

“But if I were a doctor, would I have the reach that I do now? I’m not sure I would,” Coyle says. “At the Shelden Simulation Center, I’m able to help train the next crop of medical students and have a positive impact on patients and patient care.”

Located on the fourth floor of the Patient-Centered Care Learning Center, Coyle’s workspace is part art studio, part laboratory. In the foreground from left to right: neonatal intravenous trainer, wearable arterial bleeding sleeve and severe malnutrition palpation trainer for dietetic students.

Coyle hand-illustrates instructions — a personal step-by-step recipe book, so to speak — for all his creations, including the ocular trauma repair skills trainer.

Coyle sculpts his models using polymer-based “monster clay” named for its popularity in Hollywood horror and science fiction films. The clay remains malleable indefinitely and retains even the tiniest muscular, skeletal and vascular details. The sculptures are then used to create molds.

Ensuring his trainers feel as authentic as possible is important to Coyle. To achieve this “haptic authenticity” (real feel), Coyle uses various silicone and rubber materials.

“I’m able to intrinsically change the pigmentation of the silicone that I cast here in my studio, so I can make any skin tone reflective of any population or region of the world,” Coyle said. “I also use what’s called ‘flocking’ — very small hairs or fibers of varying colors that you can put in at the mixing stage.”

Coyle’s background in art, especially bronze sculpture with professor emeritus James Calvin, has served him well in an unusual profession.

Meticulous attention to detail separates Coyle’s trainers from many currently available on the market. For instance, ocular trainers come in any eye color, and he has painted hundreds of eyeballs.

Coyle prides himself on practical solutions when constructing new products, often using hardware products for the structural underpinnings of his creations. “I go to the hardware store a lot,” he said.

Christopher Sampson, professor of emergency medicine, demonstrates for medical residents a procedure using the ocular trauma trainer. Simulation exercises such as this depend on the fidelity of the trainer to maximize transfer of knowledge.

Coyle’s portfolio contains hundreds of appendages and more than 20 prototypes, including a kit for ocular procedures, pads of lifelike “flesh” to practice suturing and infant limbs fitted with arterial tubing for neonatal nurses to practice needle insertion.