Sept. 27, 2022

Contact: Deidra Ashley, ashleyde@missouri.edu

Illustration by RJ Platto

When J.W. Sanborn established the rotation field at the University of Missouri in 1888, Missouri was still a young state. Her people, like most throughout the nation, led lives centered around agriculture. Their livelihood depended on good crop returns and healthy, productive livestock.

To help push the field of agriculture forward and provide practical answers and recommendations to Missouri farmers, Sanborn and his colleagues used the field to demonstrate the value of crop rotations and manure in grain crop production.

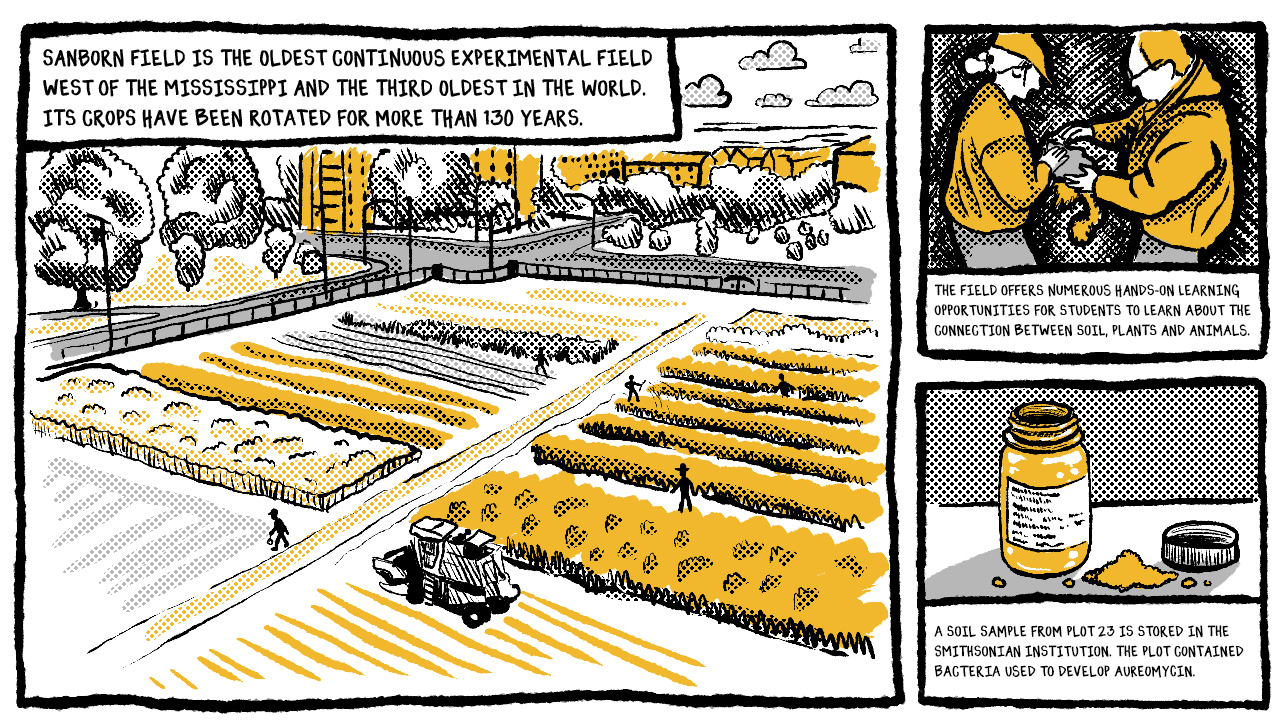

Today, the rotation field, which was renamed Sanborn Field in 1926, stands as one of the oldest agricultural research fields in the world. The area hosts 38 plots — many of which have the same crop rotations as they did in 1888. MU faculty, staff and students continue to use the field for hands-on learning, and its research findings have expanded beyond the borders of Missouri to create a global impact.

For more than a century, the farm plots at Sanborn have yielded significant scientific information about the health and best use of Missouri soils, soil erosion, fertilizer run-off, crop rotation and best methods to recover exhausted soils. But one of its greatest findings has impacted the field of medicine.

From the soil, medicine

During World War II, pathologist-physiologist Benjamin Duggar was searching for organisms that could be used to treat infections. Since soil is a living system, Duggar reached out Mizzou scientist William Albrecht to gather soil samples from Missouri that could help advance Duggar’s research. As Albrecht surveyed Sanborn Field, he knew exactly which plot to send a sample from: Plot 23.

The soil contained a golden mold that suppressed the growth of many microorganisms, including streptococci — a bacteria that causes many types of infections.

From that sample, researchers eventually created Aureomycin — an antibiotic effective against 90% of bacteria-caused infections in humans. In addition to the benefit of the drug being oral, Aureomycin was also effective treating diseases that didn’t respond to other antibiotics. It was used on humans well into the 1980s to treat illnesses such as trachoma, typhus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever and more — saving millions of lives along the way. Today, it’s still being used to save the lives of farm animals.

To celebrate the impact of Aureomycin, a soil sample from Plot 23 was made part of the scientific collection at the Smithsonian Institution, where it still resides today.