Published on Show Me Mizzou May 5, 2021

Story by Scott Wallace, MA ’83

While the month of March is renowned for the annual collegiate basketball tournaments and the passions they engender, a less raucous but no less important competition unfolds that same time of year on a corner of the University of Missouri campus. Run out of the School of Journalism and the Reynolds Journalism Institute, the Pictures of the Year contest has convened every year from mid-February to mid-March since 1943. The competition brings together photographers and photo editors to select the best images in photojournalism from the previous year.

The contest may not draw legions of boisterous fans to stadiums across the country, but its images have been seen in newspapers, magazines and online throughout the world. Many of them have shaped our understanding of both local and world events — from wars to mass migrations and from earthquakes to moments of whimsy — exercising a profound if more subtle effect on the broader public. Together, participating photographers and judges and student volunteers have pitched in to make Mizzou’s Pictures of the Year one of the most important and celebrated photojournalism competitions in the world.

This year, the contest is celebrating its 20th anniversary since “international” was first added to its name in 2001 when it officially became a program of global reach known as Pictures of the Year International, or POYi. That’s hardly the only thing unique to this year’s competition. Judges have traditionally converged on Columbia for the annual event, mingling with students over the course of a week and providing rich educational and networking opportunities in the process. But measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic turned this year’s judging into a series of virtual forums, with judges convening on Zoom to view and weigh in on the entries. To streamline the voting process, judges have been provisioned with paddles, one side green (IN) and the other red (OUT).

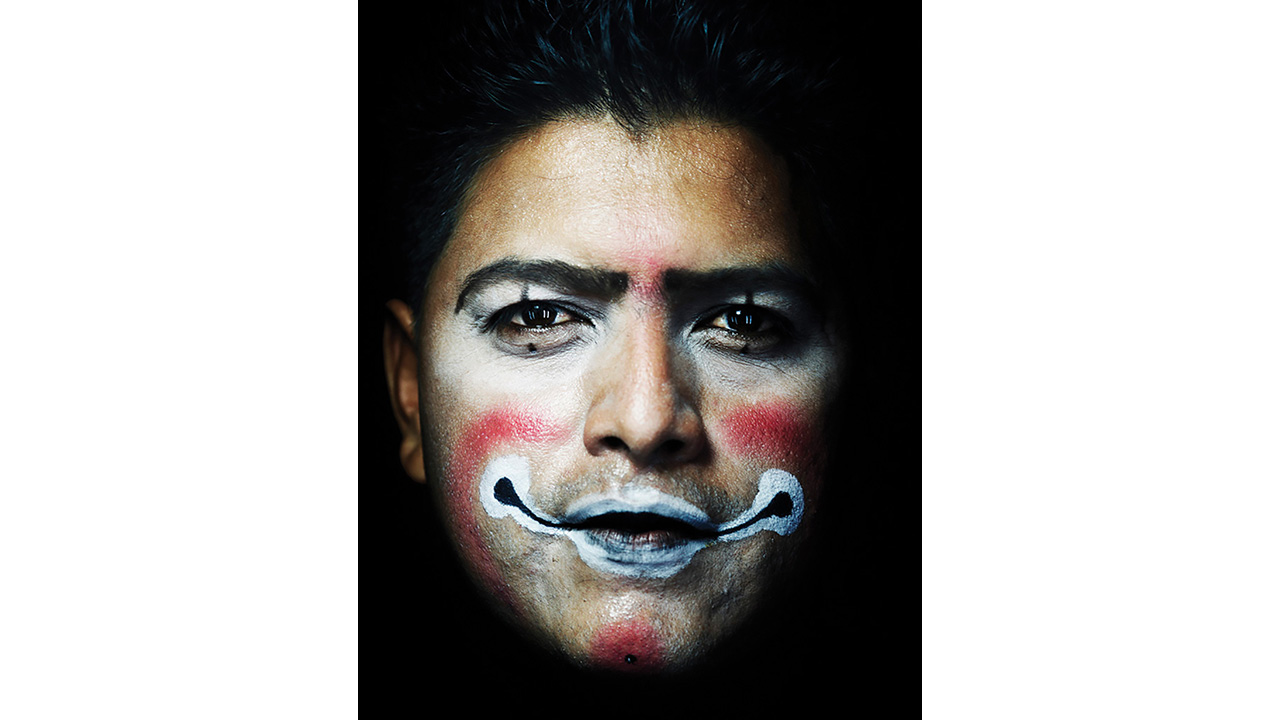

What’s more, three categories were created to address the unique set of circumstances imposed by the pandemic. One of them, COVID-19 Personal Expression, marked an abrupt departure from traditional rules of photojournalism. Manipulation of images, even staging subjects, was permitted to give photographers a broader palette to express the sense of personal loss and isolation.

This year also marks the 10th anniversary of POY Latam, an editorially independent competition created to promote the work of photojournalists from Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula. “We wanted to give Latin American photographers more exposure,” says POY Latam co-founder Loup Langton, Journ ’87. “And we wanted to give people from outside Latin America the chance to see Latin America through the eyes of Latin American photographers.” Held once every two years, the contest has doubled in size since its inception, from 650 entries in 2011 to more than 1,200 this year. “It helps you put a hand on the pulse of what’s happening artistically, cinematically and politically in Latin America,” says Pamela Yates, a film director and co-founder of Skylight, a nonprofit human rights media organization, who served as judge of documentaries this year.

That success got POYi Director Lynden Steele, BJ ’94, to think about trying something similar in Asia and set the stage for yet another milestone this year: the launch of POY Asia. Steele had first floated the idea last year with an old friend from J-School days, Kay-Chin Tay, when he returned to Columbia to judge the 2020 POYi. “Without even thinking, I said yes,” recalled Tay, BJ ’92, in a recent Zoom call from his home in Singapore. He hopes POY Asia will provide a platform for photographers from across the vast continent to discuss ideas and build community, turning the focus away from simply winning an award. “Out here in Asia, it’s really competition-crazy,” Tay says. “Every photographer thinks it’s a ticket to stardom.”

POY was originally launched in 1943 by Clifton Edom, who had arrived in Columbia the previous year to head the School of Journalism’s new photojournalism sequence. At the time, war was raging across much of the world. Allied forces were battling the Japanese throughout the Pacific. The D-Day invasion was imminent. With the global conflagration dominating the news, Edom had an idea: to hold a contest honoring the work of stateside photographers who were capturing the quiet but equally important realities of life back home in small-town America. Edom set forth a single guiding principle for the competition: “Show truth with a camera.”

The contest has expanded dramatically in scope over the past eight decades, from 200 home-front submissions in two categories — Spot News and Features — in 1943 to this year’s 40,000 images in 35 categories from photographers and picture editors around the world. As the program took hold in the 1950s and ’60s, photojournalists came to see Pictures of the Year as an important yardstick for measuring the quality of their work — its technical execution, its emotional impact.

It could also serve as a stepping stone in an increasingly competitive field. Meeting a contest judge who represented a large metro daily or national magazine at the annual event in Columbia could help make a career. As 1973 honoree Steve Uzzell, BJ ’70, puts it, “A POY award validates your vision on a high-profile stage and puts you firmly on the map.” It’s less likely today that winning an award will lead to a highly coveted staff job at a prestigious media organization. Still, entering the competition draws attention, and that’s a critical step in our media-saturated environment. Says filmmaker Yates: “It cuts through the signal-to-noise ratio.”

POYi may not have officially become an international program until 2001, but categories were evolving as far back as the 1980s that allowed photographers to submit images they’d taken on overseas assignments. By then, many regional and even local newspapers had started to send reporting teams out to cover international stories: Central America, the first Gulf War, the deployment of U.S. troops to Somalia. Come the late 1990s, making the competition international and opening it to photographers everywhere seemed a natural next step.

“It evolved from a vision to recognize the home front to a program that enabled recognition of photographers around the world, issues around the world,” says David Rees, MA ’81, who taught photojournalism at Mizzou for 32 years, directed the program during the 2000s, and oversaw the transition from POY to POYi. “I wanted to maintain the POY brand, but I wanted to enhance it.”

In recent years that enhanced brand has expanded the program into Latin America and Asia and increased the number of judges. Early on, one set of judges handled the entire contest, recalls Sarah Leen, BA ’74, who won College Photographer of the Year in 1979 as a grad student and went on to become the director of photography at National Geographic. “And now they break it up with different sets of judges, which is nice because you get a wider variety of opinions.”

For Steele, the wisdom of Edom’s original edict — show truth with a camera — remains undiminished. “It’s so simple. It cuts through so much fog.” As Steele assumed the helm at POYi in 2018, he ruminated on Edom’s vision and how it continues to resonate in the best of photojournalism so many years later. “When you think about the world, it’s filled with small towns,” Steele muses. “Most of what photography does really well is show those moments of everyday life. And then through that, it conveys stories that build empathy between people.”

Stirring empathy is a big part of what judges look for in the submissions they review. Photographers score high marks if they succeed in getting in close to their subjects to portray life unvarnished and raw, if they are able to give viewers a sense that they are present at the scene. Judging the National/International News Picture Story category this year, Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post photographer Michael Robinson Chavez urged his contest entrants to take their audiences into the story with them.

One of the many surprises emerging amid the widening circle of POYi contests is the cross- fertilization taking place between the programs. POY Latam and POY Asia are both editorially independent from the parent competition, and their staffs are free to create categories that recognize and encourage evolving trends in their respective regions. The idea for a new COVID-19 Personal Expression category, for example, came from POY Latam, which was already publishing similar images at poylatam.org/revista.

Whatever the picture category, the contest that grew up on the corner of South Ninth and Elm continues to bring together thousands of practitioners from around the world. POYi serves as a kind of glue that binds a growing community of photojournalists, all engaged in the same pursuit. “A great picture will evoke this connection between you and someone you don’t know,” Steele says. “The picture allows you to be there, alongside them in their moment. I think that’s the magic of it.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.

Setting the Standard for Photojournalism

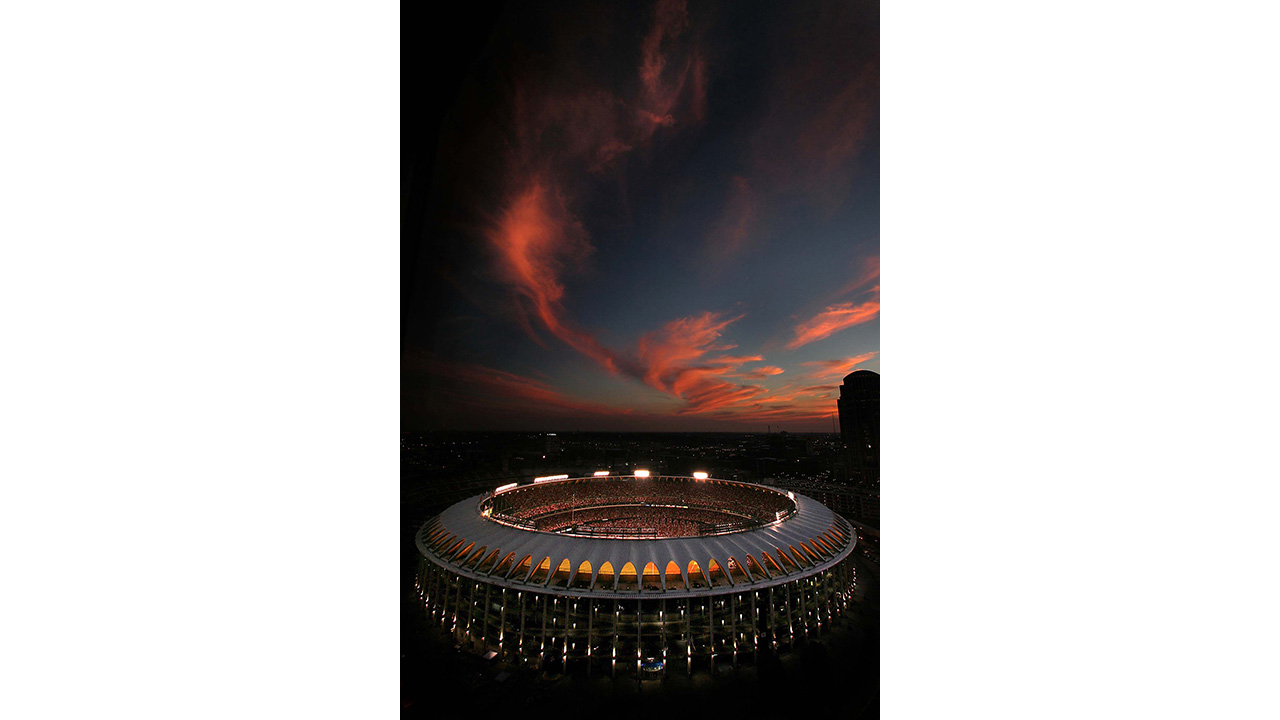

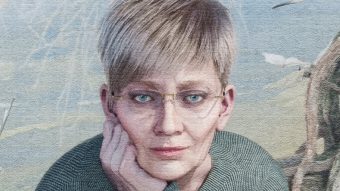

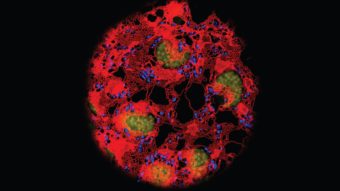

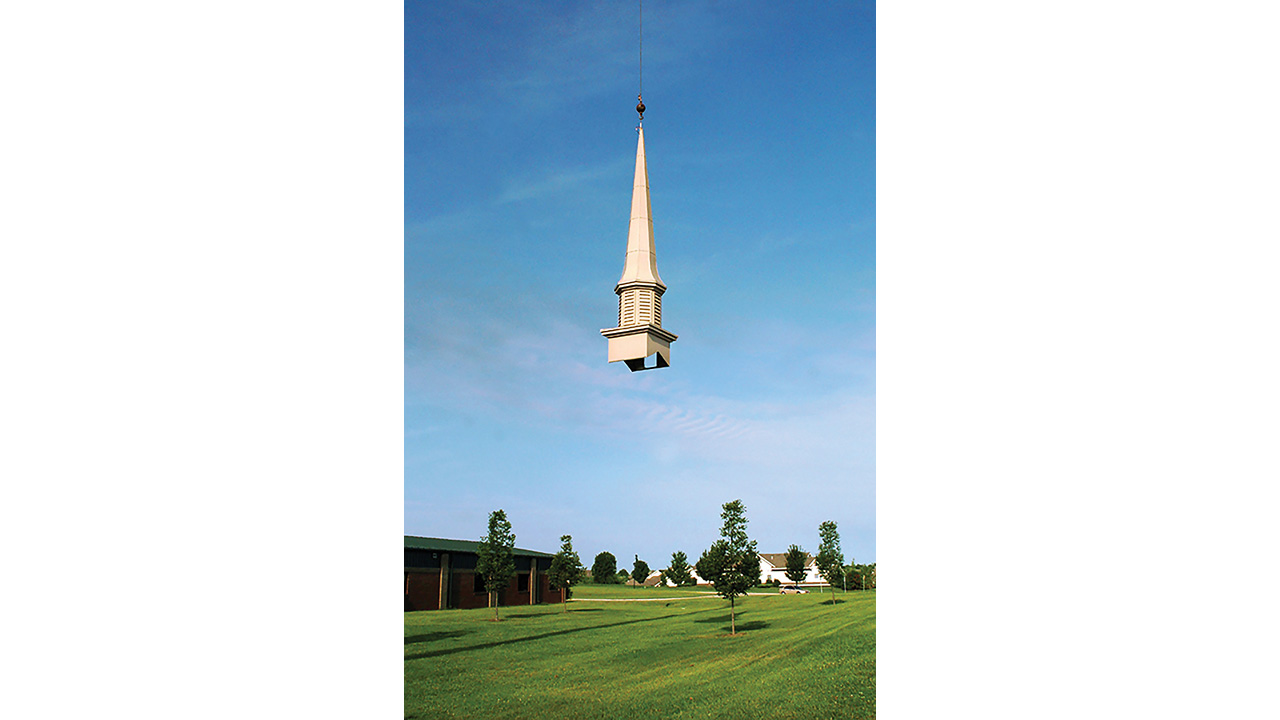

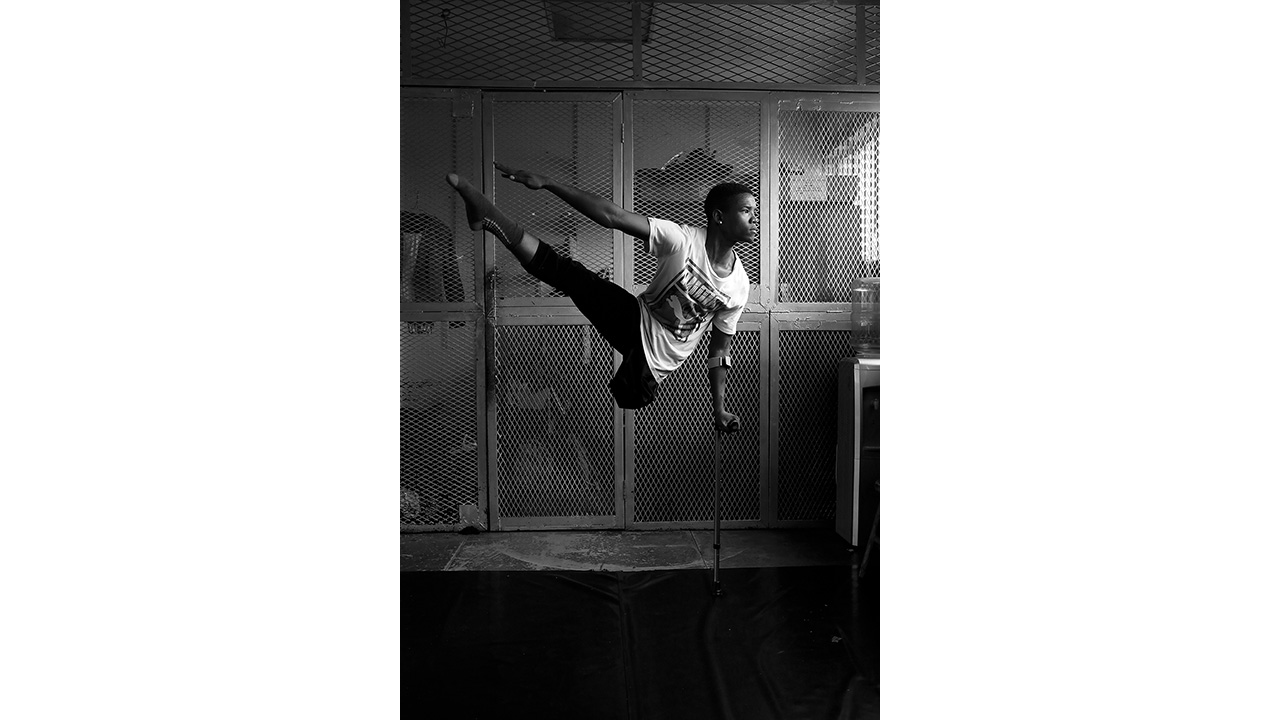

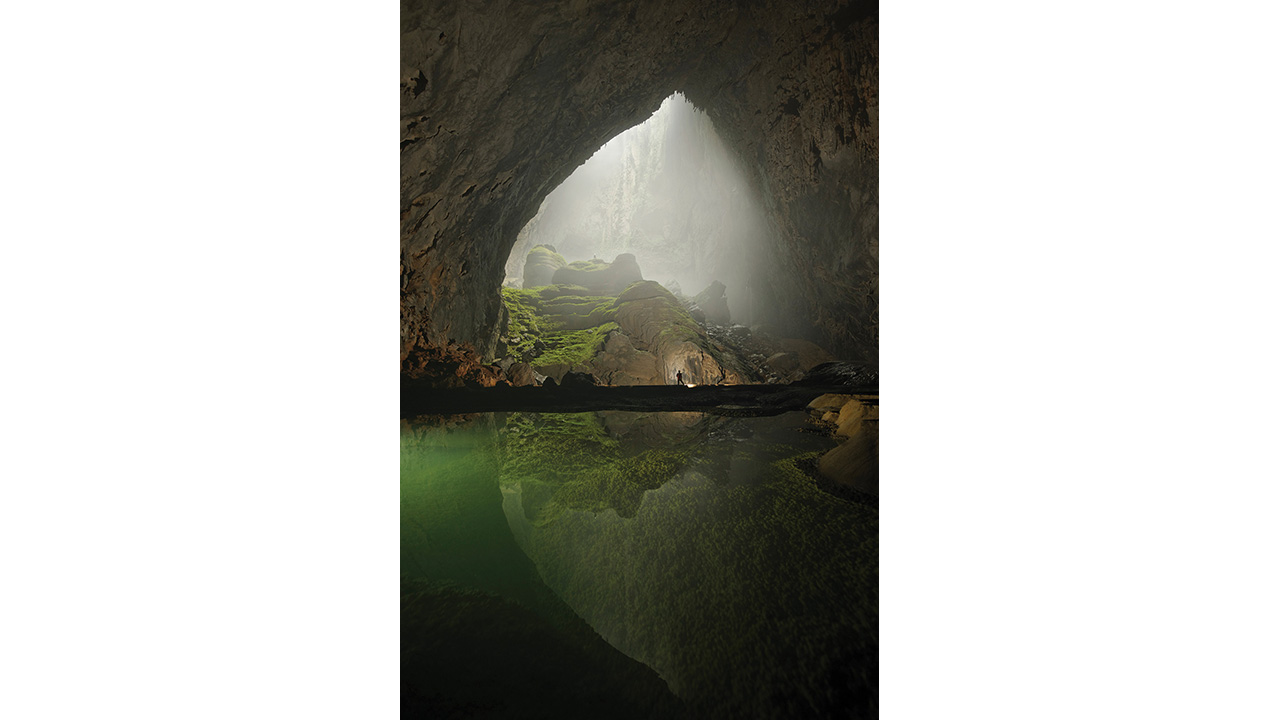

The Pictures of the Year contest has convened every year from mid-February to mid-March since 1943. The competition brings together photographers and photo editors to select the best images in photojournalism from the previous year. Many of the contest’s images have shaped our understanding of both local and world events exercising a profound if more subtle effect on the broader public. Together, participating photographers and judges and student volunteers have pitched in to make Mizzou’s Pictures of the Year one of the most important and celebrated photojournalism competitions in the world. This year, the contest is celebrating its 20th anniversary since “international” was first added to its name in 2001 when it officially became a program of global reach known as Pictures of the Year International, or POYi. Check out this sample of winners from the past two decades. More: poy.org

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.

![image002[28] Plastic waste equivalent to 33,880 plastic bottles is being mixed into the Mediterranean per minute, and "medical wastes" used during the pandemic are already reaching the seas. This image, taken underwater near the coast of Turkey by Sebnem Coskum, placed second in the Science and Natural History category at POYi 2020 and placed first in the Nature and Environment category in POY Asia.](https://showme.missouri.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/image00228-1280x720.jpg)