Katie Thompson, BS ’04, PhD ’11, has all the good problems that being a scientist-entrepreneur brings — juggling an overload of current work, along with expansion; planning; marketing; and trying to solve the urgent problem of a greening disease that’s sweeping through Florida citrus groves. She’s in the midst of remodeling the St. Louis plant that houses Elemental Enzymes, the company she and her husband, Brian, MS ’08, founded in 2011 with Ashley Siegel, PhD ’11. The company also has a field research station in Columbia and employees in Jacksonville, Florida, and Australia. Now holding some 17 agriculture patents, the company got its start in the university’s Life Science Business Incubator, which not only provided initial lab space but also helped it write a business plan and raise funds from investors.

The 40-employee firm, focused on seed treatments and plant health, needs more room. Figuring out the logistics lands on her to-do list.

“When you’re an entrepreneur, there’s always so much more work going forward,” says Thompson, who grew up in Jefferson County in Missouri and earned her doctorate at Mizzou in cellular and molecular biology. “We never suffer from a lack of work.”

Credit the University of Missouri’s long-standing emphasis on research with helping to launch fledgling companies like Elemental Enzymes. Now, an ambitious five-year plan seeks to double the amount of federal and commercial research dollars on campus by 2023 — to $410 million.

The overarching goal is to underscore the university’s mission to benefit society.

“We’re trying to boost economic development for Missouri while addressing the world’s challenges in food, water and health,” says Jeff Sossamon, assistant director of strategic communications in MU’s Office of Research and Economic Development.

The effort paid off in dramatic fashion last year, with $48 million more flowing into the campus from federal grants and corporate partnerships, a healthy 29 percent increase over the $205 million in research funding in the prior year.

“There’s been really good buy-in across the campus,” says Lisa Lorenzen, who leads efforts to commercialize faculty innovations in Mizzou’s Technology Advancement Office. “The federal support we bring in creates hundreds, if not thousands, of jobs.”

One job-creating success is a Columbia company ThermAvant Technologies and its spinoff ThermAvant International. Founded by a mechanical engineering professor and an entrepreneur, ThermAvant specializes in heat-transfer, aviation and energy technologies supported with grants from the U.S. Department of Defense and the Missouri Technology Corp. ThermAvant International sells consumer products such as Burnout, a temperature-regulating travel mug.

The university’s research push also brings in millions of dollars — and in some years tens of millions of dollars — from licensing of researchers’ patented discoveries. Bill Turpin, president of the Missouri Innovation Center, which manages the MU Life Science Business Incubator, notes that one-third of the licensing fees go to the inventors, with other portions going to the department that housed the research, legal fees and to support the university’s general research programs. “There’s usually a seven-year lag time between creation and when money arrives,” he says.

Beyond jobs and income, university research is improving lives with medical and engineering advances. One start-up created in 2018 using technology licensed from the university is Intelligent Respiratory Devices. It uses premature babies’ own respiratory patterns to regulate the supplemental oxygen they need. Roger Fales, associate professor in the mechanical and aerospace engineering department, one of the three MU inventors of the technology, says his research was motivated by the possibility of saving tiny lives.

“This technology learns from the baby how to regulate oxygen,” Fales explains. “Too little can cause brain or tissue damage. Too much can lead to blindness. Nurses can do it manually, but this takes the workload off, and there’s initial hope for superior health care outcomes.”

Mizzou’s support for his research makes the nights and weekends he devotes to this invention seem worth it. “The university has been there from the beginning with grants,” he says.

As Lorenzen notes: “The faculty is not in it for the money. They really do want to make a difference.”

To bring these successes from the lab bench to the bedside has taken new efforts campuswide.

The five-year research plan not only solicits yearly roadmaps from each of MU’s deans on how to modernize laboratories and support research faculty but also energizes how the university acquires federal grants and industry partners. An Office of Research Advancement helps reduce the administrative burden of shepherding lab discoveries to commercial success.

Brainstorming sessions on campus — Big Ideas Labs — have been set up to push collaborative research across disciplines, Sossamon notes. “We get people to spend an entire day in a room with the goal of meeting one funding opportunity.” In a recent session, engineers, computer scientists and plant scientists were so animated by the collaboration that, instead of a single idea, they hammered out four proposals to submit for a single grant opportunity. “They came up with creative ways to use artificial intelligence drones to address farming problems with precision agriculture,” he says. “The collaboration means more bang for the buck.”

Mizzou also has boosted continuing education for faculty, students and postdoctoral candidates. New hires are expected to elevate MU’s research faculty by 300 people by 2023. “We’ve already landed some world-class researchers,” Turpin says, “and there’s a bonus because they bring along any federal grants they were working on.”

A new online community, Missouri StartupTree, connects faculty and student innovators with businesses, mentors and investors. University entrepreneurs benefit from new fast-track licensing assistance and aid in determining how to commercialize their discoveries.

Major start-ups also draw on the expertise of Missouri’s research faculty to further their commercial success. Beyond Meat, with its well-known investors Bill Gates and Leonardo DiCaprio, tapped the expertise of MU professors Fu-hung Hsieh and Harold Huff to launch the company now producing the well-received Beyond Burger sold widely in grocery stores, schools and restaurants. Its manufacturing site in Columbia expanded to 100,000 square feet, from 30,000, in 2018, generating some 250 new jobs in mid-Missouri. The company also brought “a big influx” of licensing income to the university last year, Turpin says.

Gabor Forgacs, the scientific founder of Organovo, a company using cells to build living tissues, is an emeritus physics professor in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. The firm, engaged in organ printing and drug testing on blood vessels, now is traded on the Nasdaq Stock Market.

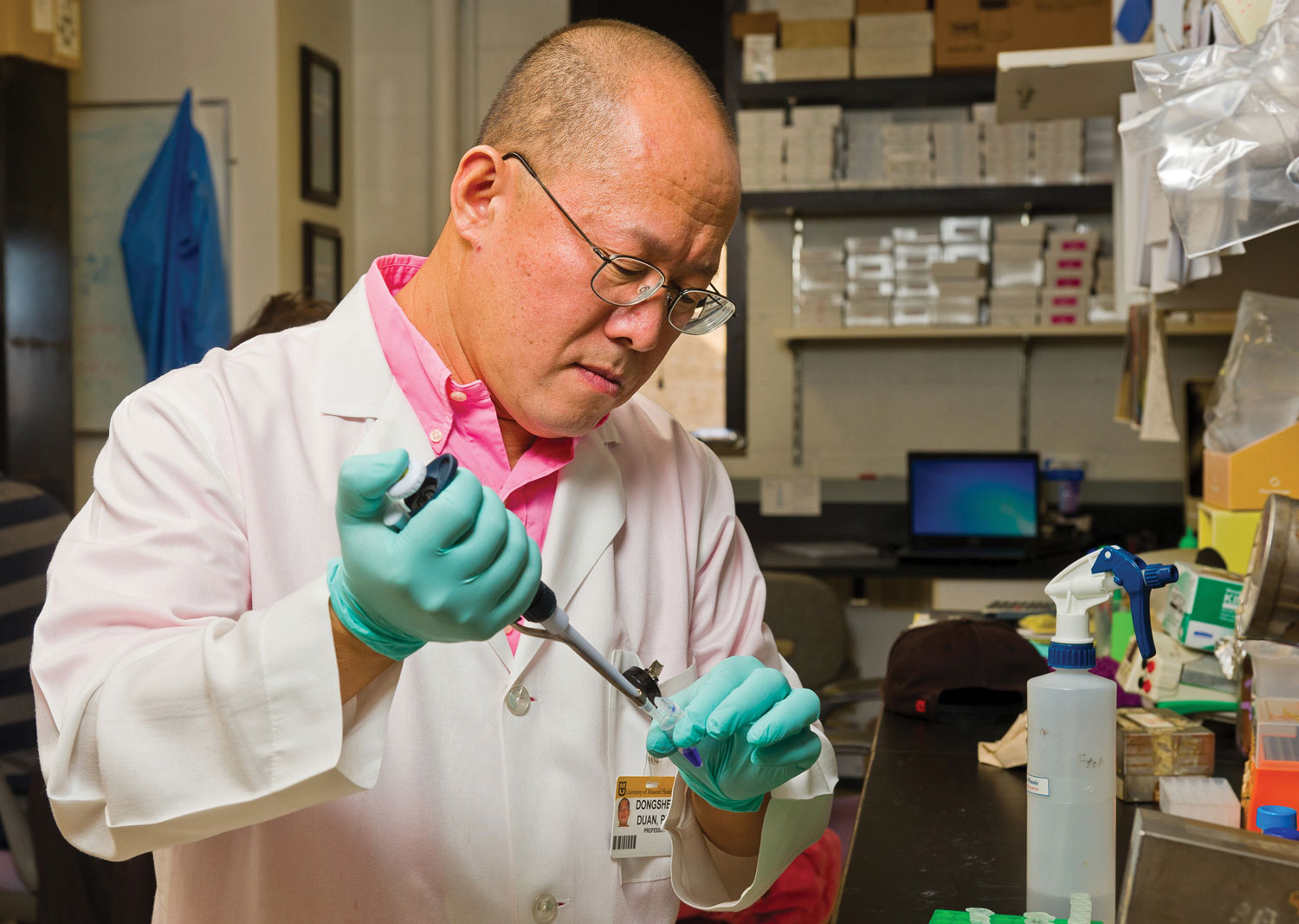

Similarly, research by Dongsheng Duan, the Margaret Proctor Mulligan Professor in Medical Research, has been licensed by Solid BioSciences, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, company that is racing to solve the mystery of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Duan also serves on the company’s scientific advisory board.

In addition to matching corporations with the right MU faculty, students also are receiving extra attention in finding commercial outlets for their research. Entrepreneur Quest, an annual contest sponsored by the University of Missouri System, gives student entrepreneurs a chance to win seed funding for their ventures.

The 2019 winner, veterinary student Libby Martin, invented a collar for pregnant cows that alerts ranchers in real time when birth is imminent. Because 10 percent of calves die during labor, often because ranchers arrive too late to help, her invention could lead to big cost savings for animal agriculture.

She won $30,000 for her “Fitbit for cows,” and her firm, Calving Technologies, already is testing prototypes in the field. “There is an unbelievable amount of resources here for students trying to do start-ups,” Martin says.

Precision health care is a big focus of the research push, as are radiopharmaceuticals and agricultural science. Next year, a NextGen Precision Health Institute will open, directing increased attention to cancer and vascular and brain diseases. All are leading causes of death for Missourians.

Medical appliances and drug discoveries are large parts of the 800 patents that university faculty created. “The ideas in our [research] portfolio will be part of the next decades’ great advancements,” Lorenzen says.

Research has a long and valued history at MU. Back in 1876, for instance, state entomologist Charles Valentine Riley helped save the French wine industry by grafting French vines onto more disease-resistant American grape roots. The veterinary science department set up the country’s first vaccine virus lab in 1885, which was followed three years later by a pioneering Agricultural Experiment Station. The U.S. Congress was so impressed by the university’s soil erosion research in 1917 that it created field stations across the country.

A vision of the importance of nuclear energy pushed the university to transform the site of a former polo field into the nation’s largest campus-based nuclear reactor in 1966. Faculty and students in multiple colleges use the now 10-megawatt facility, which anchors MU’s Research Commons.

In the following decades, the Mizzou steadily established range of research centers. Campus now houses 11 specialized centers, termed research cores, working on DNA, information research, immunobiology, X-ray microanalysis and other cutting-edge subjects.

Directing Mizzou’s research battle plan is Mark McIntosh, vice chancellor and head of the Office of Research and Economic Development. Also on the frontlines is Turpin, whose MU Life Science Business Incubator continues to house Elemental Enzymes’ field research. “Mizzou did a lot to help us,” says Thompson, who notes that the company’s first two patents were created with the university. Elemental Enzymes is now working on a protein that boosts the immune system of plants, allowing crops to fight diseases without using fungicides or other chemicals. The discovery is making its way through approvals at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “It’s a potential game-changer,” she notes.

Thompson has returned to campus to encourage students to follow her and her husband’s entrepreneurial path. “I truly hope that even more companies can start out at Mizzou,” she says. “It’s a great way to grow your research.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.