Published on Show Me Mizzou August 25, 2022

Story by Kelsey Allen, BA, BJ ’10

At a time when most women didn’t even think about having it all, suffragist Emily Newell Blair bucked conventions in the world of work and marriage as she attempted to balance a happy, fulfilled personal life of the Victorian era with the respected professional life of a more modern moment. But it cost her. In Blair’s effort to do both, she ended up living two lives, neither of which was as complete as it might have been in another age.

Despite having been born in 1877 in Joplin, Missouri, and raised there, somehow Emily Newell Blair never fit into Victorian norms or small-town life.

Her parents were transplants from back east in Pennsylvania who opened up the wide world to their children. “Exiles [my parents] felt themselves to be and so did we children,” Blair wrote in her autobiography, Bridging Two Eras. She grew up hearing stories from her father’s business trips to New York and overhearing her parents discuss commerce, politics and public events. Unlike many of her classmates, she took art classes and music lessons and studied Latin and French, and her family often read Shakespeare and Elizabethan dramas aloud together. “I was 17 before I realized I was a Missourian,” she wrote.

After graduating from Carthage High School in 1894, Blair was determined to leave the Midwest in her wake. She attended Women’s College of Baltimore (later Goucher College) — but only for a year before her father died and she returned home to help care for the four younger children. At the University of Missouri, she attended a summer session, which included a pedagogy course that helped her land a job teaching at Sarcoxie High School. The salary was welcome income at home.

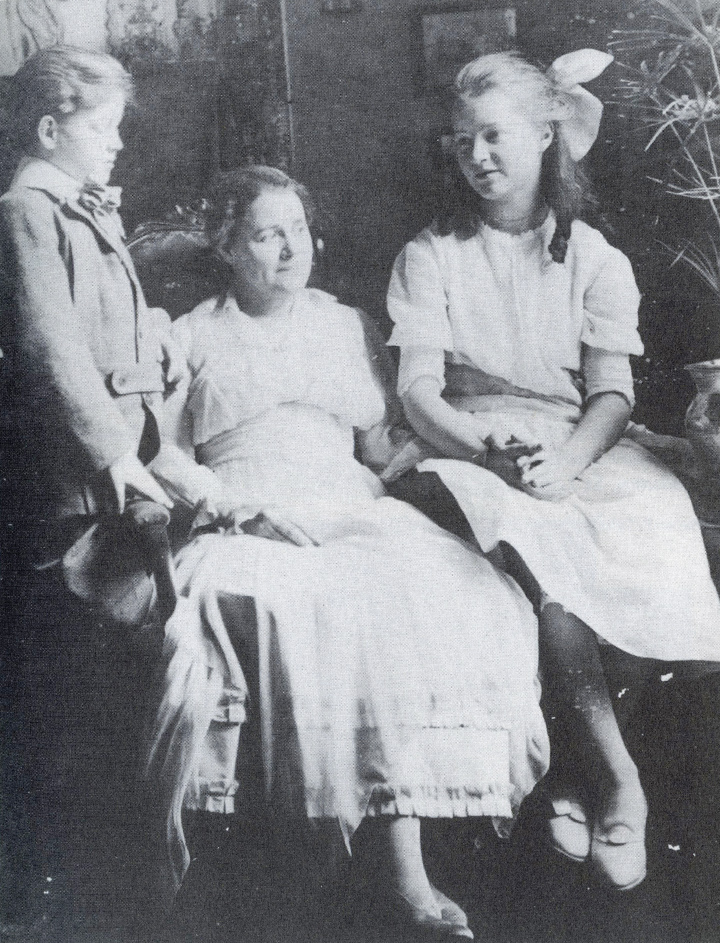

In 1900, she married her high school classmate, Harry, then a circuit court reporter in Joplin. Decades later, Blair reflected on their nuptials: “If anyone ever drew a surprise package at the altar, he did. What is more, the wrappings stayed on the package for 10 years, and all that time he thought the wrappings were the real woman. … Not that she knew they were wrappings. She did not. If anyone had told her what was inside, she would have thought him crazy. I know very well what kind of woman she appeared to Harry Blair, for she appeared the same to herself. She expected to do the same things her mother had: bear a family, run a house and spend her husband’s money.”

For a decade, while Blair’s ambitions were those of husband’s future as a lawyer, she followed the traditional paths of teacher, wife and club member. “I lived in and through him,” she wrote. Harry ran for circuit judge in 1908, and Blair managed his letter campaign, responding to citizens and newspapers across the state. He lost. But along the way, Blair acquired a taste for politics, and Harry came to appreciate his wife’s writing abilities.

One day, an issue of Cosmopolitan arrived containing the article, “Confessions of a Rebellious Wife.” Blair wondered aloud why no one writes about the happy wives, and Harry challenged her to compose such a piece herself. Almost as a joke, the 33-year-old Blair penned a retort, saying, in part: “If they had only realized that perfect understanding and trust do not happen accidentally or spring full grown from a marriage vow, but had made a little more effort, theirs might be such an ideal marriage as we are striving for — one which the foundation of faith and harmony and the atmosphere of love make perfect.” Published in 1910, “Letters of a Contented Wife” not only launched Blair’s writing career but also reinvigorated her life both in and out of the home. Within a year, her magazine articles on matrimony and domesticity appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, Lippincott, Outlook and Woman’s Home Companion.

Blair gradually traded church potlucks and home-cooked meals for luncheons with fellow writers. An organizer at heart, she founded the Missouri Women’s Press Association in 1912. Around that time, MU’s internationally respected journalism dean, Walter Williams, made her a charter member of the Missouri Writers’ Guild. Soon she was regularly appearing on campus to present talks at Journalism Week, as well as hobnobbing with New York publishers and successful writers and editors. Williams nurtured her abilities. In one exchange, Blair called him “a horticulturist who cultivates our sprigs of talent.” His reply: “I know a peach when I see one.” She later wrote it was one of the nicest compliments she ever received.

But it was an encounter with Kewpie cartoon creator Rose O’Neill, then at the height of her success, at a guild retreat that Blair recalled as truly transformational. After two days of dancing, musical performances, poetry readings and late-night discussions about Paris, books and the craft of writing, Blair was enamored and inspired. She saw in O’Neill a “free soul … untrammeled by the trappings, physical, mental, social, in which everyone I had known was bound.” O’Neill recognized the same glimmer in Blair, telling her: “Be yourself. You have it in you — the sacred fire.” Blair later wrote that she was “never afterward quite the conformist” she had been.

However, the editor of her autobiography, which was completed in 1937 but not published until 1999, isn’t as sure. “That’s just the way women in that time period presented themselves,” says Virginia Laas, professor emerita of history at Missouri Southern State University in Joplin. “I don’t think she needed anyone else to make her feel empowered. She knew she wanted to have a life other than what she had here. It didn’t take any great awakening. She probably felt the need to make others comfortable with a woman exercising power. It was somewhat unwomanly to push yourself forward in public activities. It takes her some time to become comfortable with just saying, ‘I’m pretty good at this. I have skills. I could do these things.’ ”

Regardless of whether she benefitted from encouragement, Blair was no longer willing to remain in drawing rooms and church sewing societies. Through a local woman’s club, she participated in a countywide campaign to pass a tax to build a new almshouse. Her advocacy ran the gamut from writing speeches to going door to door urging women to persuade their husbands to vote in its favor. “True, the women did not have a vote, but they did have tongues,” she wrote.

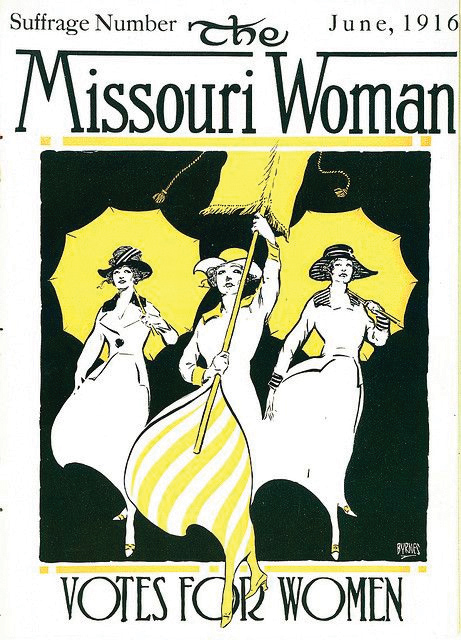

Gaining a reputation as a speaker, Blair was invited by a leader in both the state and national movement for women’s suffrage, Helen Guthrie Miller, to put her words to work. Miller offered a position that would come with a secretary, which greatly appealed to Blair, for an assistant would give her more time to write. Again, Blair called out the ego boost that came from being chosen for her skills and capabilities, the allure of escaping the cult of domesticity, and the desire to extend her sphere of influence beyond home and family. She said yes and shortly thereafter in 1915 became the first editor of Missouri Woman, the monthly magazine for the Missouri Equal Suffrage Association.

Both experiences broadened her horizons beyond small-town Missouri life. “There came to me the thought, ambition, or temptation, whatever it was, that my life need not be bounded by the four walls of a home,” she reflected. “Another way to put it would be that the cocoon of Victorianism was beginning to crack.”

With this growing sense of conviction, Blair began working 18-hour days while also rearing two children and supporting her husband’s law practice. It was taxing, and she often struggled with guilt. “The fact was that … I had put the suffrage activity first,” she wrote. “Although never put into words, I knew my husband felt this. Something had gone out of our relationship. The realization was bitter medicine.” In an attempt to better balance professional fulfillment and private happiness, Blair declined an invitation from Carrie Chapman Catt to come to New York and work for suffrage at the national level. For the next two years, she worked in Missouri as vice chair of the Missouri Woman’s Committee for the Council of National Defense and as president of the Carthage Equal Suffrage Association.

In 1918, when Harry volunteered to go overseas for the YMCA during World War I, Blair quickly wired Catt that she was available. A week later, Blair was in Washington, D.C., publicizing the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, which organized women’s role in the war effort. She threw herself into the job, writing an interpretive history of the committee, honing skills as an organizer, and working closely with Ida Tarbell and Anna Howard Shaw.

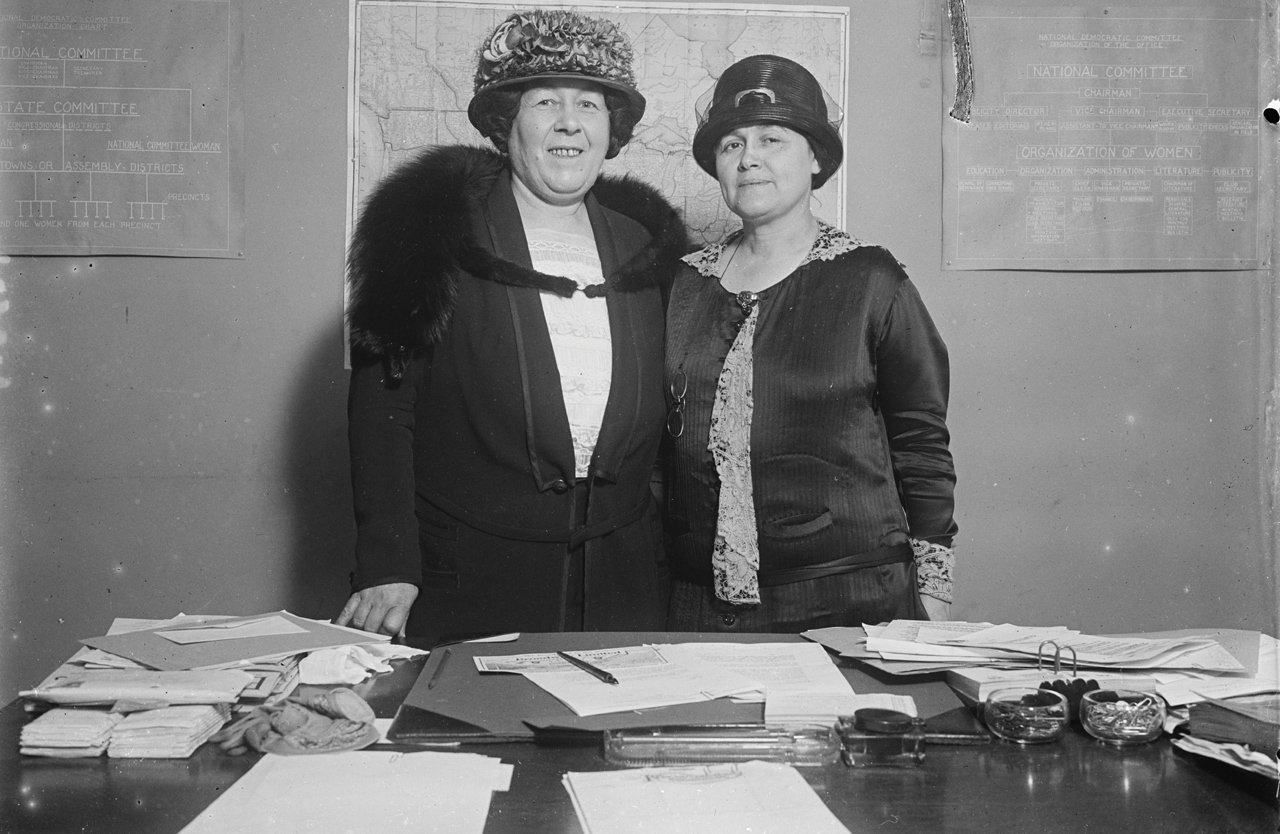

Harry returned from France in 1919, and the Blairs moved back to Missouri — Harry happily and Emily reluctantly. After the 19th Amendment gave women the vote in 1920, Blair helped found the Missouri League of Women Voters and turned to integrating women into party politics. She was elected Missouri’s committeewoman to the Democratic National Committee. The following year she became the vice chair of the Democratic Party, the first woman to hold that position in either major party.

Blair was a force in Missouri, Laas says. “She was very intelligent, but she also was very much a lady. She wasn’t in your face, but you knew that she was serious about what she was talking about.” One Missouri politician nicknamed her Southern Comfort because she “goes down so smooth and easily but has an awful kick afterwards.”

Using Missouri as a model, Blair organized more than 2,000 Democratic women’s clubs across the country, sponsored Schools of Democracy in each region and, with the help of Daisy Harriman, formed a national Democratic Women’s Clubhouse in D.C. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported her nickname as “the little Napoleon.” During these years, Blair continued to write on women, politics and public life, and from 1926 to 1933, she was an associate editor of Good Housekeeping, writing a monthly book column.

But Blair was still based in Joplin. “It took a great deal of energy and time to live two lives simultaneously,” she wrote of her frequent and sometimes extended trips to the East Coast. “She spent years struggling to pry Harry out of southwest Missouri and get him to go east,” Laas says. “But he would have been perfectly happy to practice law in Carthage the rest of his life.”

Again and again, Blair rode her ambition to the brink of damaging her marriage and then pulled back to her family responsibilities. “Blair’s desire to balance personal ambition with marital harmony is also an apt illustration of her contention that women of her generation bridged two eras, from Victorian to modern times,” Laas wrote in “Reward for Party Service: Emily Newell Blair and Political Patronage in the New Deal,” a chapter in the book The Southern Elite and Social Change. Blair wrote that “It takes wisdom to know how far she can sacrifice her family without danger to something more valuable than her work, and how much she is really required, in justice to all, to sacrifice her work to her family.”

Ultimately, Blair could have been the assistant secretary of state in the Roosevelt administration and instead asked for a position for her husband. “She had always overshadowed Harry,” Laas wrote in “Reward for Party Service.” Blair knew Harry would only move to Washington — where she wanted to be — if he were offered a job. She used her influence, and Harry was eventually appointed assistant attorney general in charge of the lands division. The decision brought stability and marital harmony, but it cost her prestige and power.

“She didn’t become the central figure she could have been in the network of women active in the New Deal,” Laas says. Instead, she served as chair of the Consumer’s Advisory Board of the National Industrial Recovery Act and chief of the women’s interest section of the War Department’s Bureau of Public Relations. She retired after suffering a stroke in 1944 and died in 1951.

A little over a century after Blair helped secure women’s right to vote and rose high in national politics, Laas says there’s much to learn from her story: “If nothing else, she gives us insight into how difficult it was for women to walk that line — to try to get equal rights for women and still have happy, personal relationships.”