February 1, 2021

Story by Sara Diedrich

Darryl Chatman will never forget the father-son journeys to the airport to watch planes land. He was 9, sitting shotgun in the old blue Pontiac, a ribbon of blacktop unspooling behind them in the fleeting day. It was a short drive from their mobile home in O’Fallon, Missouri, to the St. Louis Lambert International Airport. The elder Chatman, a draftsman by trade, was an aviation buff and eager to share his passion with his namesake. Their anticipation was palpable. Not far from the landing strips, they’d park, cut the engine and scramble out. Sometimes they’d sit on the trunk or hood for a better view. They’d watch until stars pierced the night sky.

Those lessons in wonder were decades in the making. Chatman’s grandfather, who never graduated from high school, was nonetheless a believer in education. He sent all eight of his children to private high school. When his turn came, Chatman’s father, who grew up in the Pruitt-Igoe housing projects in downtown St. Louis, sent his son to private school from kindergarten through high school. The youngster may have been too young to grasp those generational sacrifices, but he did inherit the love of learning. After arriving at the University of Missouri in 1992 on a football scholarship, he went on to earn four degrees from Mizzou and a fifth from North Carolina State University.

Chatman has risen quickly through a pressure-packed law career. But it wasn’t until January, when the 46-year-old father of three took the helm of the UM System board of curators, that he felt the full weight of all his father and grandfather had given up for him. As chair of the nine-member board, he oversees the operations of all four of the system’s campuses — MU, University of Missouri–St. Louis, University of Missouri–Kansas City and Missouri S&T. And he doesn’t get to quit his day job as senior vice president of governance and compliance at the United Soybean Board in Chesterfield, Missouri.

“My father and grandfather never told me it would be an easy road,” Chatman says. “They were so proud that I was living the dreams that they had envisioned for me.”

Trophy for Dad

Chatman was born in St. Louis and grew up in North St. Louis County. When he was 4, his 2-year-old sister died from sickle-cell anemia. His parents later divorced, and Chatman split his time between both homes. To keep their son busy and out of trouble, they signed him up for Boy Scouts and every sport available. It would be his saving grace.

His father struggled with addiction to alcohol until Chatman was 10. He remembers visiting him at the hospital where he was recovering. It was near Father’s Day, and the boy had brought a gift — a trophy with the inscription: World’s Greatest Dad. “He broke down and cried,” Chatman recalls.

His father still had the trophy years later, when Chatman asked why he had quit drinking. “He said because he loved me and wanted to be the best dad that he could be for me.” His father remained sober and an active member of Alcoholics Anonymous for the remaining 35 years of his life. He died in March 2020 about a month after his wife, Chatman’s stepmother, passed away.

No. 1 fan

By the time Chatman reached Lutheran High School North, he was an outstanding athlete, excelling in football, basketball and track. He placed second in the state in shot put and discus, and his football team won the state championship his junior year.

His father and stepmother had moved to Olivette, Missouri, where Chatman joined them for his senior year of high school. He had grown especially close with his father, who never missed a chance to see his son compete. He also shared with Chatman his love for space and technology and found ways on a tight budget to buy his son a telescope and a Commodore 64 computer. He even took Chatman to Florida to watch a space shuttle take off. “He was really interested in getting me on the cutting edge of technology and understood the importance it would play in my future,” Chatman says. “He really wanted me to be curious about the world.”

And all along, his father never complained. Instead, he embodied the humility that comes with hard work, sacrifice and a belief in something greater than himself, Chatman says. He was an eternal optimist, no matter the mountain to climb. “He didn’t have the money to do what he did for me, but he did it anyway,” Chatman says.

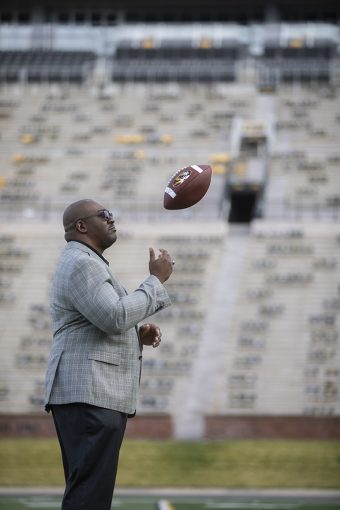

The gridiron

A heavily recruited football linebacker, Chatman chose Mizzou where he brought with him his father’s dogged determination and grit, earning him the nickname “Chopper” and a reputation as one of the most feared defenders in the Big 8 and Big 12 conferences.

Coming to MU was a big step for Chatman, who admits he had lived a rather “sheltered existence” before coming to college. But it didn’t take long for the new recruit to catch the eye of seasoned players who recognized his potential. “They took me in and told me: ‘Hey man, you’re only doing what you’re required to do. You need to do more. What do you think you’re doing here? We didn’t come here to be average; we came here to be great,’ ” Chatman says. “That became the norm for me. Those guys did that for me, and they made it fun, too. You have to have that good core of people who will push you to be better.”

To this day, those players remain close friends, checking in with one another daily. Among them is Mark Alnutt, BA ’95, MPA ’00, now athletic director at the University at Buffalo. After football, he and Chatman roomed together while both pursued graduate degrees at MU. “Darryl is a worker. He is relentless in a positive way,” Alnutt says. “He was committed to sports and earning his degrees.”

Lifelong learner

In 1994, Chatman took his first undergraduate course in animal science from Professor Jim Spain, now vice provost for undergraduate studies and eLearning at MU. It seemed an unlikely subject area for a student from the city, but Chatman was enamored with the topic and the people he met in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources.

The feeling was mutual.

Spain was struck by Chatman’s sense of wonder and massive appetite for learning. “Darryl has this natural curiosity that I think has led to the trajectory of his significant success,” Spain says. “He brings that same commitment of lifelong learning that we talk about as an institution to everything he does.”

Chatman was never afraid to ask for help, and like his father and grandfather, he never shied away from hard work or an opportunity to get his hands dirty. After graduating with a degree in animal science in 1997, he earned graduate degrees in animal science in 2001, agricultural economics in 2007 and a Juris Doctorate in 2008. During those years, Chatman held down two, sometimes three jobs to make ends meet. He worked as a janitor at University Place Apartments, a farmhand at the Mizzou dairy farm and a meat cutter at the Mizzou Meat Lab, all experiences he credits with keeping him right-sized. “Those blue-collar jobs were the best things that ever happened to me. I learned the value of hard work. I built a lot of comradery with the people I worked with, and it was very humbling.”

Since then, Chatman has applied those lessons in humility to every job he’s held, no matter his title. Chatman has served as general counsel for the Missouri Department of Agriculture and as an attorney with Armstrong Teasdale LLP in St. Louis, where he led the firm’s agriculture and biotech practice group. From January 2015 to January 2016 he served as the Missouri Department of Agriculture’s deputy director.

Richard Fordyce, now administrator of the Farm Service Agency for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, hired Chatman as his deputy director. He recognized immediately that the charismatic man who arrived for the job interview could make an impact on farmers across the state. He wasn’t disappointed. “Not only is Darryl curious, but he is incredibly genuine.” To this day, farmers still ask Fordyce: “Have you talked to Darryl lately? How’s he doing?”

A dream fulfilled

After serving as a member of the board of curators during a tumultuous three years that included leadership changes and financial shortfalls, fellow board member Maurice Graham, BA ’60, JD ’62, nominated Chatman for chair in late 2020. He says Chatman understands the important balance between sharing his own thoughts and ideas and listening respectfully to the input of others. He has noticed that Chatman asks tough questions when necessary, and he never misses a chance to express appreciation. “He has a strong passion for the mission of the university and its four campuses.” As chair, Chatman will prioritize supporting research across the campuses and building on programs that help students succeed.

He had not imagined being a member of the board of curators, much less its chair. Both accomplishments brought him to tears. “These are things I never thought possible for me,” he says. “I’ve had great mentors in the past who told me, ‘Darryl, you don’t dream big enough.’ This was something that wasn’t even on my radar, but here it is; it happened, another dream fulfilled.”

Chatman’s top priorities as chair of UM System Board of Curators

Drive research: “We need to continue supporting research and building our research enterprise across all four campuses. NextGen will be very important for us moving forward.”

Support student success: “I really believe that students are the core of what we do. So we have to do everything we can to help our students achieve success, whether that is providing different support networks, more outreach or educational opportunities.”

UM System Board of Curators

The University of Missouri System Board of Curators is a nine-member board that oversees all four campuses: MU, UMSL, UMKC and Missouri S&T. Members are appointed by the governor with advice and consent of the Senate. At least one, but no more than two board members, shall be appointed from each congressional district. Each member must be a citizen of the United States and have lived in the state of Missouri for at least two years prior to appointment. No more than five curators can belong to any one political party.

Curators serve six-year terms, and three are replaced every two years.

Today, the UM System is one of the nation’s largest higher education institutions, with nearly 70,000 students on its four campuses and an extension program with activities in every county of the state.