Published on Show Me Mizzou April 24, 2025

Story by Kelly Caldwell, BJ ’88

Illustrations by Serge Bloch

I was 19, self-conscious, as quick to mortification as some drivers are to road rage, so, really, the incident should have killed me.

On an 80-degree day in mid-April, another reporter walked into the Maneater office wearing a jacket and heavy blue wool sweater.

“Take that sweater off!” I said. “You’re making me hot just looking at you!”

The room erupted into a middle school, “OhhhhhhOOHHHHoooohhhhhhhhhhh!!!” The next thing I knew, someone dragged over a chair. An upperclassman named Fred grabbed a fat black Magic Marker and started inscribing my words high onto the walls of Read Hall.

It was one of the proudest moments of my life.

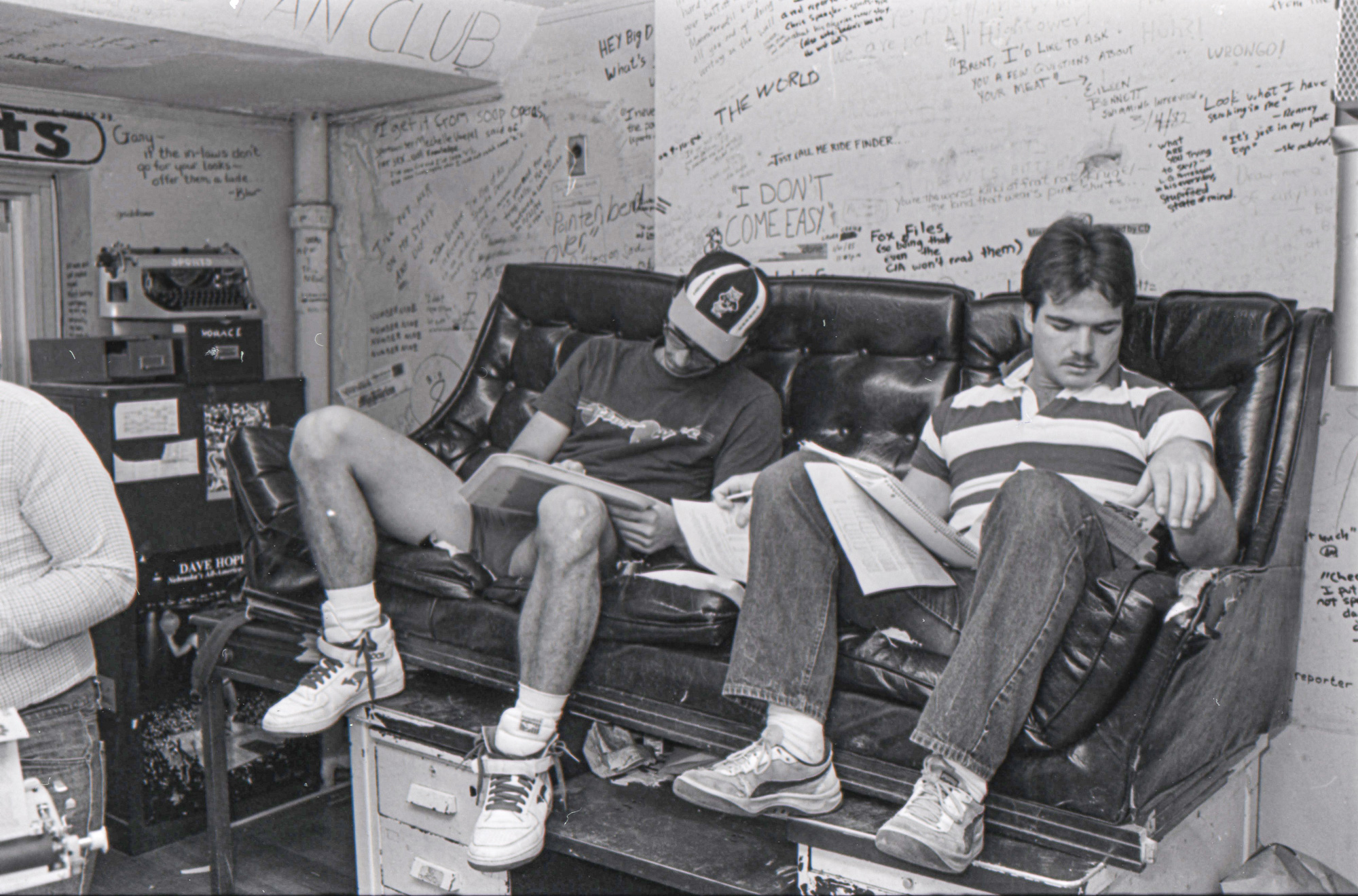

For at least 15 years in the ’70s and ’80s, the Maneater’s offices on the third floor of Read were legendary for the graffiti covering every inch of the greenish-gray walls. Ceilings, too. It was of varying vintages, some so faded you could barely read them, and the handwriting fluctuated in its legibility, too. There were a few drawings, but mostly, it was text. You couldn’t make the wall with something so generic as your initials or “Kilroy was here” or “Jane Jake.” You earned your way onto the wall with bits of philosophy, threats, jokes, insults and assorted weird nonsense muttered at 4 a.m. on production night:

“I’ve got a lot of patience. And that’s a lot of patience to lose.”

“The Digest is turning into a good paper.” (No doubt that was a sick burn when Eric said it in 1979, but I never figured out whether the burnee was the Digest or Eric.)

“You have to choose someday whether you’re going to be a journalist or a human being.” Underneath, someone replied, “Man, I hope you have a good alternative.”

It wasn’t Basquiat. But it was ours.

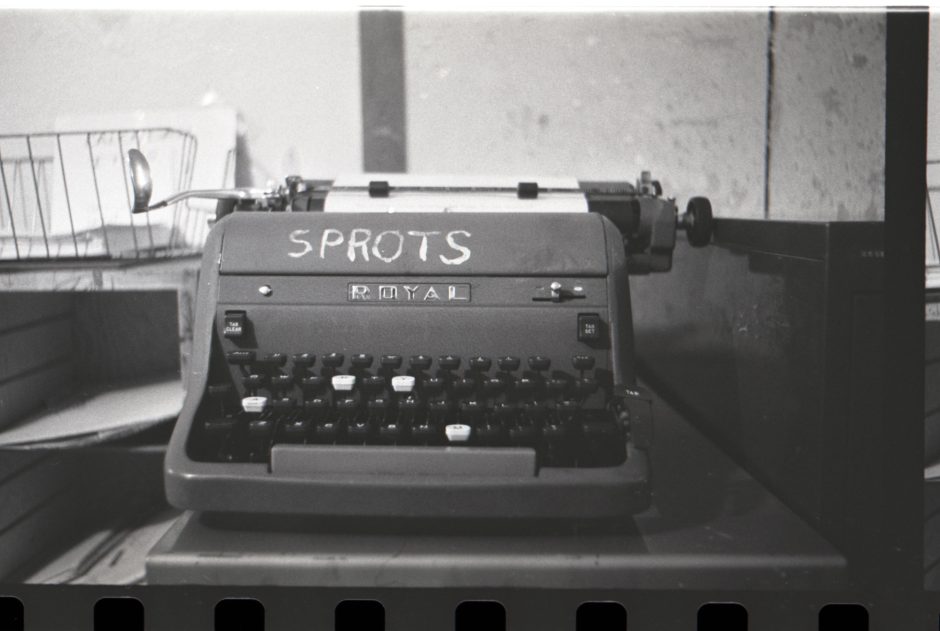

Soon, it would be gone. At the end of that school year, the university would kick the Maneater out of Read Hall and move us into bigger, cleaner, more modern quarters in Brady Commons, where we’d be able to produce the paper with actual computers instead of the manual typewriters and rubber cement we’d been using since the Wilson administration.

Click here to view Kelly Caldwell’s deconstruction of this memoir in our printed magazine.

We lobbied hard to stay, but the administration rejected all our appeals. To the university, I suppose, one set of rooms was as good as another for the scruffy loudmouths who published the student newspaper. No doubt they thought we were being overly sentimental.

It was so much deeper than that.

What we had is called place attachment — a strong cognitive-emotional bond with a space where you’ve had intense personal experiences. It can develop because of the nature of the experience or because it took place in a community or because the place itself is special. Sometimes it’s all three.

Think of all the classes you took in GCB/Strickland Hall — what do you remember? Maybe those skinny windows were on the left side of your Spanish classroom and the right side of your algebra classroom. Or was it the other way around? Does it matter?

Now imagine an earthquake hit the Francis Quadrangle. Two Columns lay on their sides, split in half. The other four are nothing but dusty chunks. That sensation you’re having right now of being stabbed in the heart? That’s place attachment.

Sure, Read Hall was special to us because it’s where we met our closest friends, saw our first byline, suffered heartbreaks, celebrated victories. It’s where we crafted, issue by issue, the story of our adult lives.

Those pivotal, life-changing moments happened to us elsewhere on campus, too, on Lowry Mall or in Middlebush Hall. But our affinity for those spaces was never quite so fierce as our attachment to Read.

The difference is the graffiti.

We liked its audacity, this open, gleeful defacing of university property. It appealed to our desire to be perceived as rebellious, independent, willing to speak truth to power.

It also gave us a sense of legacy: Every scribble connected us to aspiring journalists who became the real thing. We sat where they sat and hoped to follow their bad puns into careers of our own.

But most importantly for creating that cognitive-emotional attachment, the graffiti changed the physical space. Nowhere else on campus looked like the Maneater offices, and that made them indelible. It made events within those walls more vivid, special. We read it, preserved it, shared it, added to it. Hell, we curated it.

It’s why my “Take that sweater off!” moment was so joyful. In the fall, it had taken me a full month to work up the nerve to attend my first Maneater news meeting. By then, the campus had stopped seeming so overwhelmingly huge, and I’d met the woman who would become my best friend. I’d attended enough home football games to say hi to the students who sat in my section.

But as a shy kid eight hours from home, I still felt like a visitor, not yet fully a part of university life. Mizzou still did not belong to me. Not yet.

That feeling started to fade after I finally dragged myself into Read Hall and one of the editors read out the last story to be assigned. “You there,” he said, pointing at me in the back of the room. “What’s your name? This one’s yours.”

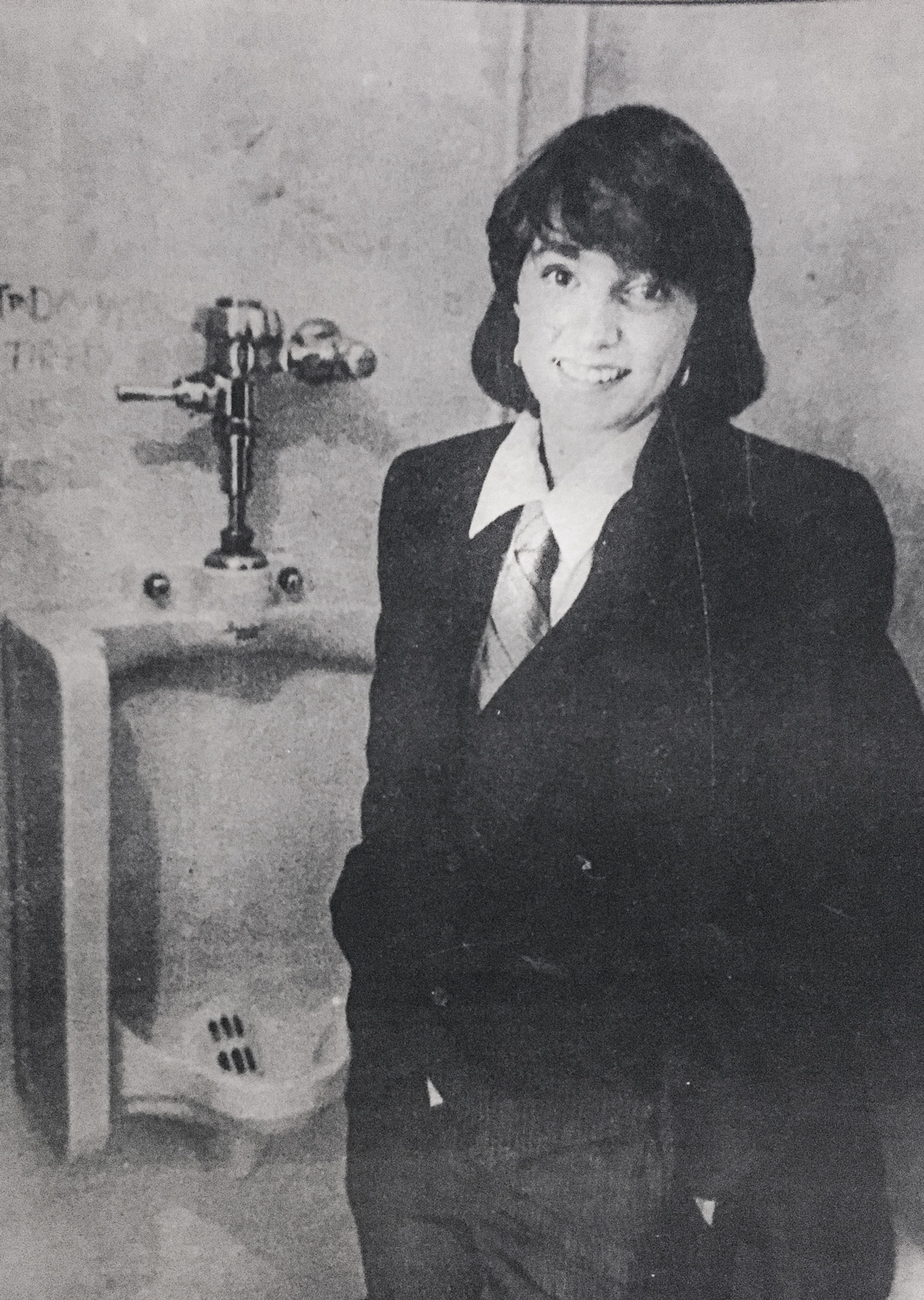

Now, I was being immortalized for saying something really dumb. My fellow writers were teasing me with, “What else would you like him to take off, Kelly?” and “Is there anyone else you’d like to see strip, Kelly?” Now, just like Patient Laura or Eric ’79, I’d made the wall.

That one was mine.

As the school year wound down and the move loomed, we were in genuine mourning. Some ’eaters declared they’d never set foot in the offices in Brady Commons, and they kept their word. Others tried but soon drifted away. It wasn’t the same. As promised, the space was clean and modern and sterile and windowless. Those of us who continued to work on the paper didn’t bring our place attachment along with us.

After the Maneater’s move, a rumor went around that before construction workers took sledgehammers to the walls, tearing them down to the studs and rebuilding them, a couple of editors tried to chisel out hunks, to save some of the quotes. The plaster crumbled in their hands.

Age, cigarette smoke, neglect — there were plenty of sound, logical reasons why we couldn’t take those pieces of Read Hall with us.

For me, though, it’s more likely that the graffiti was an artifact, ancient and enchanted. It could not survive outside its temple.

Kelly Caldwell, BJ ’88, who has published in Vox, House Beautiful, Newsday and The Writer, teaches memoir and leads the faculty at Gotham Writers Workshop in New York City.

Click here to view Kelly Caldwell’s deconstruction of this memoir in our printed magazine.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.