Published on Show Me Mizzou April 24, 2025

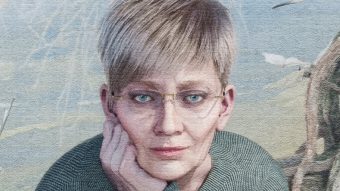

Story by Nina Mukerjee Furstenau, BJ ’84

Photos by Abbie Lankitus

Stephen McKaskle dips his hand into a bin and holds out his palm.

“You’re looking at the oldest rice variety in America,” he says, sifting through brownish and blunt-tipped grains. “Carolina Gold.”

McKaskle’s family farm is in Braggadocio, in the bootheel of Missouri. The farm raises rice, soybeans and popcorn on 5,000 acres and sells his rice to Whole Foods, Chipotle, Fresh Realm and others. It also sells directly to customers under the brand name Braggadocio.

“The original variety was grown in South Carolina,” McKaskle says. “Carolina Gold, by itself, doesn’t do very well here.” He adds that Santee Gold, a hybrid, fares better. Holding out a palmful of another cultivar (short for plants of a “cultivated variety”), he touches a few grains. “This one is Neches.” Another dip into a bin. “Brown Basmati.”

Rice and heartland America might not seem like an obvious pairing, but Asia’s terraced and flooded fields have had counterparts here since colonial times.

“We’ve got at least 15 cultivars that are commercially grown in Missouri,” notes Aaron Brandt, director of the T.E. “Jake” Fisher Delta Research, Extension and Education Center.

The center supports Mizzou’s research and educational programs tailored to the Southeast Delta Region. Located in Portageville, the center encompasses 1,119 acres across five sites. Its focus is improving key regional crops, including soybeans, cotton and, yes, rice.

Missouri mainly produces long-grain rice and a handful of jasmine varietals. Although more than 1 million acres are cultivated in nearby Arkansas, the Bootheel’s 200,000 acres of rice crops are significant in one of the richest agricultural regions in the state.

McKaskle says his operation has sold 3.6 million pounds of climate-friendly regenerative rice in the past year. The Braggadocio brand carries enough weight that when a bullet pierced the windshield of one of his combines a few years back, McKaskle saw it as a warning — perhaps retaliation after a brand he supplies spoke out against genetically modified rice in a documentary.

Another area producer, third-generation farm Martin Rice, has grown the grain on 7,000 acres in southeast Missouri since the 1970s and now plants jasmine, medium, long grain and organic rice. Arkansas-based Riceland, the world’s largest farmer-owned cooperative for milling and marketing rice and soybeans, refines Bootheel rice through a facility in Poplar Bluff, Mo.

In addition to Missouri and Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas farmers grow about 3.6 billion pounds of rice annually.

Perhaps even more surprising is that the Bootheel’s success with rice production — ranked fourth in the U.S. — is due to a public works project that was, at the time, among the largest in the world. It involved draining a swamp and moving more earth than during the construction of the Panama Canal.

Amber waves of … rice

United States rice cultivation began in the 17th century and owes the seeds of its economic power to South Carolina. The crop thrived under the care of enslaved people from the Rice Coast of West Africa (modern-day Senegal, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Liberia and parts of Guinea) who were targeted due to their familiarity with farming Orza glaberrima rice. The plant was perfect for South Carolina’s wet soil, and American rice was soon competing with rice exported from India into Europe by British colonialists.

Rice was transforming dining tables across America, too. An early cookbook by Sarah Rutledge, “The Mysterious Lady of Charleston” who penned The Carolina Housewife in 1847, included 100-plus recipes requiring the grain.

Then nature intervened: The 1911 Charleston Hurricane swept away South Carolina rice fields, hovering for more than 36 hours. The region’s crops of Carolina Gold washed down the river and, with them, the entire industry.

Interest in the grain remained. By the 1960s, Missouri farmers were cultivating rice in earnest, says Mollie Buckler, chief operating officer at the US Rice Producers Association. She’s also the staff liaison to the Missouri Rice Research & Merchandising Council, a partner to Mizzou’s agronomy program.

Buckler, BA ’10, M Ed ’12, says that rice first gained purchase in Stoddard County in 1910. Nearly 75 years later, enough rice was being produced that farmers established the Missouri Rice Research and Merchandising Council.

“I think it’s really interesting when the land supports something new to the area,” Buckler says. “The people start adapting to having a food crop they may not have had before. It changes things.”

Swamplandia

The arrival of rice farming in Missouri and other states owes much to that 1911 South Carolina hurricane. Still, earthwork and irrigation systems enabled by the development of steam power and advances in pumping technology were just as crucial. Political will did the rest.

The Little River Drainage District was formed to drain Missouri wetlands.

At the time, the region was mired in marsh, not much valued in the early 1900s. The region between the Mississippi and St. Francis rivers was host to cypress, oak, willow, tupelo, all manner of waterfowl, catfish, bass, mosquitoes, frogs, toads, cottonmouths, copperheads and surely alligators until it was drained.

Topography defined the project. Geiger says the land descends 100 feet in elevation between Cape Girardeau and the Arkansas-Missouri state line, a long, slow decline of about one foot per mile. The slope is steep enough for water to flow through 958 miles of ditches and 300 miles of levees.

By the end of 1928, 1,700 square miles, nearly 1.2 million acres, of highly fertile silt-rich land in Missouri was accessible. Afterward, timber and railroad companies harvested its valuable trees, some of them 27 feet in diameter at the base, until the timber was gone. Then the land was sold or often planted in cotton.

Nearly a century later, Missouri earns more than $246 million in annual revenue from rice, according to the USDA 2023 State Agricultural Overview — from an area that previously did not have a tillable acre in sight. Although Southeast Missouri is among the least economically developed regions of the state, it nonetheless produces one-third of all the state’s rice, soybeans, corn, cotton and wheat.

Currently, 31.5 million gallons of water pass through the drainage system every year. All that water is another advantage for Missouri rice farmers.

“Some places are losing a lot of their groundwater and having to pull water from deeper depths,” says Justin Chlapecka, a rice specialist. “We’re in a unique spot. Our aquifer will naturally deplete maybe 567 feet during the summertime when we are irrigating, and then the aquifer goes right back up to where it was. It’s recharging every year.” A former Mizzou researcher, Chlapecka recently joined the University of Arkansas as an assistant professor and research agronomist.

Milling perfection

Inside the McKaskle mill, rice kicks through metal cylinders created to separate the grain from the chaff. Other machines cull broken rice from full grains, while others grind off rice bran to reveal white rice. It’s loud, surprisingly tidy and runs smoothly with few interruptions. Nothing is wasted. Not the rice grits (pet food), the hulls (animal bedding) or the bran (livestock feed ingredient).

Each grain runs through the mill twice to remove foreign materials. “This is where true quality control occurs. This is how you get a bag of perfect rice,” McKaskle says.

History also runs through this equipment — not just McKaskle family history but the story of rice in America. There are continuing struggles. The farm surrounding the family home was hit by a category EF4 tornado in 2006 that destroyed various structures, including the main house, vehicles, machinery and crops.

Then, after Chipotle stopped using genetically modified ingredients and aired a streaming series called Farmed and Dangerous, a .22 caliber bullet shattered the windshield of a Braggadocio combine harvester. McKaskle, who was interviewed for the documentary, suspects the shot came from a farmer with a different perspective.

He also faced ongoing health challeng-es. The community of farmers has dealt with the dev-astation caused by dicamba, a herbicide that kills nonresistant crops. In relatively flat areas like the Bootheel, it can spread 15 miles, making his organic crop rotation unsustainable.

McKaskle pivoted by adopting climate-friendly regenerative farming techniques and sourcing organic rice from growers farther away, beyond dicamba’s reach, ensuring a safer and more sustainable operation. The goal is fundamental.

“We’re growing food right here,” he says.

Shaping the land

Buckler had connections to rice before she began working in the industry. “My family has been farming for three generations in southeast Missouri,” she says. “I have rice producers in my family.”

The span of Buckler’s family farming operations follows the state’s rice timeline and the Mississippi Delta’s fertility. She calls Southeast Missouri “kind of an anomaly. We’re able to grow not just rice, but watermelon, and potatoes and peanuts, and crops you don’t see around the rest of the state.”

“All of our research faculty are very grower-focused and really drive their program by solving relevant problems,” Fisher Delta Center Director Brandt says. One emphasis: how rice is grown.

To optimize opportunities, the center focuses on researching rice varieties and hybrids, furrow-irrigated rice and sustainable water use, rice researcher Chlapecka says. Furrow irrigation involves watering crops through shallow trenches called furrows rather than flooding entire fields, while flood irrigation relies on reshaping fields with levees to hold water.

“Furrow-irrigation was probably less than 1% of our acres until about 2017, and now it’s 30% of Missouri [rice] acreage,” he explains. Missouri farmers typically rotate rice with soybean plantings, which makes furrow-planting appealing. Rotating crops is simpler because soybeans and rice can be grown in the same fields without removing levees.

Flood irrigation, still used in 70% of Missouri rice fields and 80% of Arkansas fields, requires reshaping fields with earth movers. Chlapecka notes that this process can involve multiple passes with equipment to build and later dismantle the levees. This significantly increases labor and resource demands.

Furrow-irrigated rice fields have a slight gradient and, as part of a Fisher Delta Center research project, a pump at the low end recycles the water back to the top to release again between rice furrows.

Regardless of irrigation method, Chlapecka says that the state has seen top yields in the last three years. “I’d say the new average is 7,700 pounds per acre or 171 bushels.” That’s about 30,000 cups of cooked rice per acre.

He partially attributes rice yields at that level to getting better hybrids. “We’re 70% hybrid rice, and hybrid rice is going to yield at least 10% better on average.”

Rice variety trials are set up at the Fisher Delta Center and the Missouri Rice Council’s research farm 30 miles from Glennonville, Missouri. In 2024, 24 varieties at 21 sites were used for trials across Missouri’s five major rice counties (Bulter, Stoddard, Pemiscot, New Madrid and Dunklin).

Chlalpaka says many farmers now use variable rate seeding, which means adjusting seed density based on water availability, “You don’t spend any more money overall, but you’re putting seeds where they’re more beneficial.”

Walking near the rice fields on McKaskle Farm, you can see a vast amount of land and rice, even though no flooded paddies are visible. Rice stretches across the landscape, much like in photos from Asia, appearing flatter while still conveying a deep history.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.