By Eric Stann

April 29, 2025

Contact: Eric Stann, StannE@missouri.edu

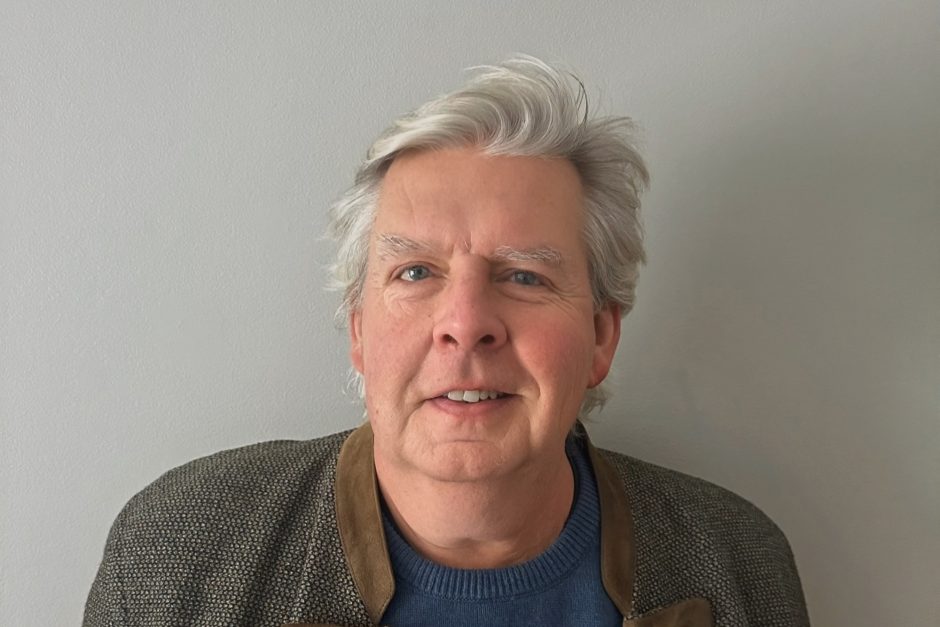

Although he was not an official Vatican employee, in the late 1990s John Frymire, now on faculty at the University of Missouri, was part of a small academic team granted access to the previously secret archives of the Holy Office — the Roman Inquisition and the Index of Prohibited Books, now called the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

At the time, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, received permission from Pope John Paul II to open this once secret archive at Vatican City, the headquarters of the Catholic Church, to scholars. The goal was to examine and modernize the organization of these archives for historical research.

While earning a doctorate from the University of Arizona, Frymire spent seven years studying in Austria, Germany and Italy. He is the first North American scholar given full access to the secret archives of the Holy Office.

Because the archive was not officially open at the time, and there was no formal way to get inside, Frymire gained entry daily through Ratzinger’s office, thereby becoming familiar with Vatican staff and Ratzinger himself — who would later become Pope Benedict XVI. Frymire said their relationship developed through a shared German background — and by his habit of bringing traditional German breads and sausages.

Now, as an associate history professor in Mizzou’s College of Arts and Science, Frymire reflects on the current events at the Vatican following the death of Pope Francis.

What are the key steps that follow the death of a pope and the selection of a new pope?

After the death of a pope, the first official step is to confirm his passing and then destroy the Fisherman’s Ring, a symbolic seal used on official church documents. A tradition dating to at least the 13th century, the ring serves as a safeguard against forgery during the transitional period.

During this time, known in Latin as sede vacante ("the seat being vacant"), no major doctrinal or institutional decisions are allowed. Governance of the church temporarily falls to the camerlengo, an official appointed by the pope prior to his death. The camerlengo oversees the daily operations of the Vatican and is responsible for organizing the papal funeral, which typically occurs within a week of the pope’s death.

All cardinals are summoned to Rome for the election, although only those under the age of 80 are eligible to vote. Once all voting cardinals are present, the conclave officially begins following a special mass, and all proceedings take place in the Sistine Chapel.

The election process requires a two-thirds majority vote to select a new pope. Voting can occur up to four times per day.

How has the papal selection process evolved over time, and what historical events have influenced those changes?

The papal selection process has been shaped by historical events and the shifting balance of power between the church and secular authorities. In the early centuries, when Christianity was persecuted, popes — then known as bishops of Rome — were typically elected by local Christian communities. This informal and localized process changed dramatically after Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in 313 CE and began influencing church affairs, establishing a precedent for secular intervention.

As the Roman Empire collapsed, popes had to navigate power dynamics with emerging European rulers. Some, like Pope Gregory the Great, maintained independence, but many others were influenced or even appointed by secular powers. This imbalance reached a low point during the Carolingian period (circa 700–1000 CE), when papal authority was especially weak.

In the centuries that followed, especially during the Renaissance, secular influence persisted despite reforms, leading at times to morally questionable popes. The church responded by further insulating the election process, and introducing the conclave system — known in Latin as cum clave (“with a key”) — to ensure cardinals voted in seclusion.

In modern times, few major structural changes have occurred. Pope Paul VI’s 1970 reforms limited the number of voting cardinals to 120 and set an age limit of 80. The number of cardinals allowed to vote has grown over time — in the coming weeks, about 135 will be able to take part in the election.

Technological advances have since improved the security and confidentiality of conclaves, and the global nature of the church has led to a more geographically diverse College of Cardinals. Despite these developments, the underlying goal of preserving the independence and sanctity of the papal selection process has remained constant throughout its history.

The Sistine Chapel plays a major role in the conclave. Why is it used, and what is the significance of holding the election there?

The Sistine Chapel is used for papal conclaves because of both its practical and symbolic qualities. Originally chosen even before Michelangelo’s artwork, it was valued for its size, isolation and security — ideal for the privacy needed during the election process. After Michelangelo completed his iconic frescoes, especially “The Last Judgment,” the chapel gained deeper spiritual significance; the artwork was seen as invoking a divine presence, encouraging cardinals to reflect on divine judgment while voting. Additionally, the chapel has historically served as both a sacred and functional space for the pope’s daily activities, making it a natural and meaningful setting for choosing his successor.

Many are familiar with the black and white smoke signals used to communicate the election's progress. Can you share how that tradition began and how it’s executed today?

The tradition of using smoke signals during papal elections began in the 19th century, when cardinals started burning ballots after each vote, with smoke indicating a failed election. At that time, the absence of smoke signaled that a new pope had been chosen. In the early 20th century, a temporary chimney was added to the Sistine Chapel, and the black-and-white smoke system was formalized. Initially, different types of wax were used to color the smoke, but the results were sometimes unclear, producing shades like light gray that confused observers. To fix this, starting in 1963, specific chemicals were used to ensure distinct black or white smoke. Since 2005, the Vatican has also rung bells along with the appearance of white smoke to clearly signal the successful election of a new pope.