March 21, 2025

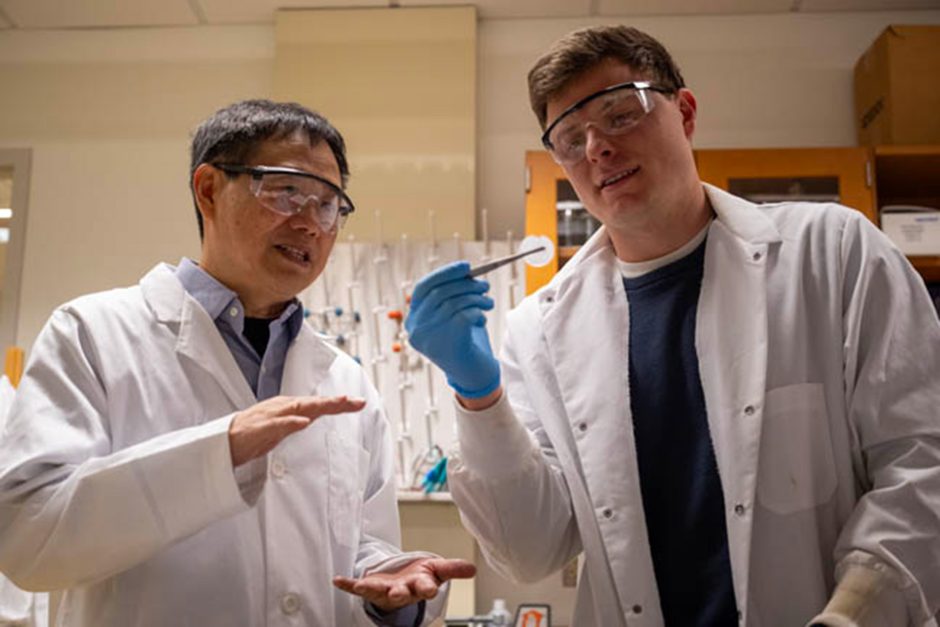

Photo by Zac Anderson

A University of Missouri engineering researcher has found a way to extract rare earth elements from mine waste. The solution, described in the journal Separation and Purification Technology, helps address a critical need for these materials.

Rare earth elements are essential to manufacture permanent magnets used in electric vehicles, wind turbines and other advanced technology. This study focused on neodymium, one of the most valuable elements, which is present in significant quantities in an inactive iron mine in Pea Ridge, Missouri, in the Ozark Mountains.

“Rare earth elements are vital in manufacturing all sorts of technology products, and Missouri could play a major role in addressing their shortage in the U.S.,” Baolin Deng, Curator’s Distinguished Professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, said.

To extract the neodymium, John Earwood, a doctoral student who led the project, fabricated two types of hydrogels that can selectively bind neodymium. The main ingredient in these gels is chitosan, a biodegradable, non-toxic material that is a waste product from the seafood industry.

“It comes from the exoskeletons of shrimp and other crustaceans, so it’s sustainable and relatively low-cost,” Earwood said.

But mine waste is acidic, which can weaken chitosan and make it less effective for extracting elements. To remedy this, Earwood dissolved the chitosan with a solvent of alkali salts to make it stronger.

He then treated the resulting polymer with two separate crosslinking agents to create two stronger hydrogels, which he submerged in mine drainage containing neodymium and other elements.

“These hydrogels were very effective at adsorbing neodymium, even in the presence of other rare earth elements in the mine drainage,” Earwood said. “This shows that the materials can be used effectively in a variety of conditions, which is important for real-world applications.”

Mizzou’s proximity to Pea Ridge and the support of mine owner James Kennedy presented a unique opportunity for Earwood.

“Pea Ridge has one of the most significant concentrations of rare earth elements in the United States. We’re incredibly lucky to have that in our backyard,” Earwood said.

Earwood cautions that further research is necessary before the process can be implemented at a larger scale. While doing so could improve access to rare earth elements, it would only be part of a broader strategy, not a complete solution to supply challenges, Earwood said.

“Scaling this technology would create new supply streams from previously untapped sources, which would reduce our dependence on foreign sources and breathe new life into old mines,” he said.

Read more from the College of Engineering