Published on Show Me Mizzou April 24, 2025

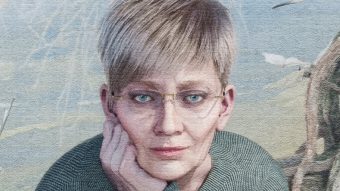

Story by Kelly Caldwell, BJ ’88

Illustrations by Serge Bloch

Warm football Saturdays. Wandering the stacks at Ellis. A bronze tiger statue. A menu featuring chicken-fried steak. Something puts that faraway look in your eyes and unleashes your best stories — and it need not trigger an urgent need in your spouse or kids to check their phones. You can hold their attention while reliving your best moments. In fact, you should. Because looking back is just another way of moving forward, and your audience will feel the same acceleration. Read on as teacher and memoirist Kelly Caldwell unloads her best tips and tricks for composing a favorite episode from your campus years.

Side by side in the smallest apartment in Columbia, Sherry and I taught each other how to fry bacon.

We were sharing a studio on Rosemary Lane that we’d nicknamed “The Closet.” It could fit one single bed, so we took turns sleeping on the floor. We had a kitchen chair, too, but it went into the hallway when both of us were home at the same time.

It felt like living inside an oil can, and that summer, Columbia suffered a record-breaking heatwave. I spent my last dollar on a used window air conditioner and stored it overnight with a boyfriend. He sold it.

He was why Sherry was there with me, clogging her pores in The Closet at midnight when she should have been in a cool movie theater with a date of her own. After an argument with the air conditioner thief, I’d called her in tears at work; she came home instead.

She should have called me a putz like she did whenever I slept through our 8:40 a.m. Econ 51 class and needed to borrow her notes. She should have banned me from hanging out, eating Oreos and gossiping at her second job at the Brady Commons commissary until I’d broken up with the air-conditioner thief. She should have told her co-worker to take a message.

Instead, Sherry held my hand until I calmed down. Then she stood up, stuck the chair out in the hall and proclaimed, “I’m starved! Aren’t you starved?”

Of the countless nights I’ve stayed up too late eating fried foods with friends, this one stands out. I could joke that it’s memorable because of the Missouri summer heat, my almost nonexistent cooking skills or my questionable diet.

But that would be glib and unsatisfying. And it wouldn’t be true in the deepest sense. As a writer and teacher of memoir, it just won’t do.

That’s because in memoir, we excavate and share our memories not just to entertain friends or bathe in the balmy breezes of nostalgia. We also examine them in the hopes of unearthing deeper truths about what it means to be human.

Click here to read Kelly Caldwell’s Maneater memoir

Our college years — when our prefrontal cortexes are in the final stages of development, when we’re gulping down knowledge like thirsty hippos drinking water, and when we’re experiencing more big firsts than we can count — are especially rife with memories begging to become meaningful stories. They’re also likely to bubble up to the surface with the slightest provocation: the mere existence of a football Saturday, the smooth spine of an old book, the tang of pizza sauce.

Once they’re unlocked, though, then what?

First, write them down before they have a chance to skitter off and get lost forever. Writing them down also may summon other memories you can preserve. Before you know it, you’ll have a notebook full of stories you didn’t even know you remembered.

If you’d like to take it further, to craft those stories into memoir and discover why they’re meaningful to you, read on.

How often have you heard someone say, “Someday, I’m going to write my memoirs, and then everybody better watch out!”? What they really mean is, “Wait till I write my autobiography and exact revenge upon all those who have wronged me.”

As fun as it might seem to write a vengeance-inspired hit job, a memoir is a story written for other people. It’s also one story of your life, not the story of your life. That’s autobiography, which is mostly reserved for the super famous (or infamous): politicians, inventors, performers. Think of last year’s Lovely One by Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson or the much-anticipated life story forthcoming from pop star Lionel Ritchie. Their successes are the destination; all that remains is to answer the question, “How did I get here?”

There’s no preset destination for the rest of us; any moment in our lives that feels urgent and memorable to us can be the focus of a good memoir. Everyone’s life is full of potential meaning— no fame required.

But we have to narrow and narrow and narrow the focus of our story. You don’t want to tell the whole story of living in your sorority or choosing your major or courting your spouse. You want to single out one moment that sings to you and write it down. Where was it? What music was playing? When did it happen? Who said what? Repeat for the next moment. And then the next.

You wouldn’t throw flour, sugar, butter and cherries into a blender, dump them into a pan and bake them, and expect them to turn into a pie. The same goes for memoir. You create each layer individually, then knead them together into a whole.

Often the moments that sing to you are when something disrupted the status quo of your life. Spring comes too early, prompting two best friends to commit to bottling a record amount of maple syrup. A tornado rips through your community. You land the lead role in the campus production of Angels in America.

But great memoirs can start with a change that’s so small it wouldn’t be remarkable, except that it led to something more meaningful. You start going to the pizza place for lunch every Tuesday instead of every Wednesday and develop a friendship, ultimately an important one, with another regular customer. You attend the same St. Patrick’s Day party every year, but one year you wake up the next morning with a hangover, a wad of cash you didn’t have before and no memory of how you got it. (This sounds like the beginning of a thriller, but it happened to my grandfather.)

There’s meaning in the mundane. A friend’s father used to order a chocolate cake to be delivered to their home every Saturday morning. Sweet routine, right? Maybe not much more than that — until you learn that he grew up as one of nine hungry children and spent most of his childhood scrounging food for his younger siblings. Even then, with that crucial detail, it still isn’t a story. It becomes a story when the bakery van breaks down, or the mother gives the cake away to a neighbor’s family, or the dog eats it. Because then you have to answer the question, “What then?”

In her memoir Eastern Circle, forthcoming next year from Holt publishing, Catina Bacote describes how her grandfather looked out for the Connecticut community she grew up in. He scared off stray dogs and bullies, broke up fights and somehow materialized whenever anyone needed help. Again, it’s lovely but mundane. It becomes meaningful when we learn that “Dada” died protecting his community. He was shot to death defending teenage neighbors under attack by strangers.

Now it’s a story, albeit one that needs a focus. Bacote finds that when she discovers a monument overlooking the neighborhood that honors long-dead soldiers who fought in long-ago wars. She argues a similar monument should be built to honor her grandfather and the thousands like him killed in violence during the crack epidemic of the 1980s. You can see that idea in the subtitle for Bacote’s book: Searching for a Just End for My Grandfather’s Murder.

Now, it’s a story.

Sometimes, you can describe an important memory to the point of exhaustion — capturing every word spoken, the slant of the sunlight, the smell of lunch bubbling over on the stove — and still, you have a memory, not a memoir. What’s missing is the action within yourself.

“Interiority moves us through the magic realms of time and truth, hope and fantasy, memory, feelings, ideas, worries,” Mary Karr writes in Art of Memoir. “Whenever a writer gets reflective … she moves inside herself to where things matter and mean.”

You’re looking for something more nuanced and granular than, “We broke up, and I felt sad.” Events trigger internal responses, and those responses shape us: our actions, our dreams, our fears, our hopes. The stuff meaning is made of.

How many times have you walked Mizzou’s Quad on a Homecoming weekend past crowds of alumni of all ages, staring at the Columns with misty eyes? You might assume they’re all feeling the same wistfulness and nostalgia. You’d also be mistaken.

Sure, some may be ruminating generally on the past because the Columns represent the whole Mizzou campus, all the places where they did some of their most important growing up. But others may be reliving meeting their best friend in Switzler Hall or breaking up with their first love in front of the chancellor’s residence or registering for classes in Jesse Hall after overcoming enormous adversity to be able to attend college at all.

Click here to read Kelly Caldwell’s Maneater memoir

They may all be united in their nostalgia, but not all nostalgias are the same. They can be a longing for one’s past, or a yearning to reconnect with something forgotten. Humans can feel nostalgia for the future, or for a past that never existed.

My favorite description, though, is from the novelist Michael Chabon. “It’s the feeling that overcomes you when some minor vanished beauty of the world is momentarily restored,” Chabon wrote in an essay on nostalgia for The New Yorker. “In that moment, you are connected; you have placed a phone call directly into the past and heard an answering voice.”

All those misty-eyed alums on the Quad might not be listening to the same voice, but I like to think they’re sharing a party line to the past. In that way, they’re connected to each other.

That connection, too, is the strain of nostalgia that’s most useful to us in our quest to turn our memories into stories, because despite its bad reputation as a sappy time-waster, nostalgia can be an effective tool. Not only does it churn up memories and emotions — also known as material — it is useful in other ways. It prompts us to reach out to others (research), it opens conversations on long-forgotten or long avoided subjects (discovery) and it fosters empathy (just a good thing generally).

It might sound daunting, diving into the crowded madhouse of your memory, grasping one moment from the many, and then trying to study it while it bucks and flips. But you already have practice at this. Think of all the times you’ve been at a party and pulled out an anecdote to share, changing it slightly depending on your audience. Leaving out the NC-17 parts when your boss is there, opening with the NC-17 parts on a bachelorette weekend. That’s memoir.

It’s also an opportunity to visit places and eras that no longer exist, with people (including your younger self) who no longer exist — except within you. It’s a chance to return with a gift better than any snow globe: a story that helps you understand yourself better and maybe helps others understand themselves better, too.

Take that night frying bacon with Sherry in The Closet. For years I thought of it as a story about heartbreak or about navigating romantic relationships or maybe about cooking. Only when I wrote it as a memoir did I finally understand: That sweltering summer, Sherry showed me what it takes to be a real friend. It’s listening even when you want to shake someone by her shoulders and tell her to snap out of it. It’s sacrificing a night at the movies because someone you love needs you. It’s showing up, even when it’ll be uncomfortable.

Like stepping onto campus as a freshman, you never know what you’ll find when you wander into your memories and look for the stories they hold. And like the adventure you embarked on then (and the adventures since), you navigate by reaching for what seems promising and see which ones lead you home.

For an example of a short memoir, take a look at the following story about Read Hall, with a few tips and tricks in the margins. Then try to write a memoir of your own. Think of a moment from your time at Mizzou that’s calling out to you. See how much of it you can remember. Ask yourself why it’s singing to you. See what answer floats in through the open window.

Click here to read Kelly Caldwell’s Maneater memoir

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.