By Eric Stann

Oct. 16, 2025

Contact: Eric Stann, StannE@missouri.edu

Photos courtesy Marcello Mogetta

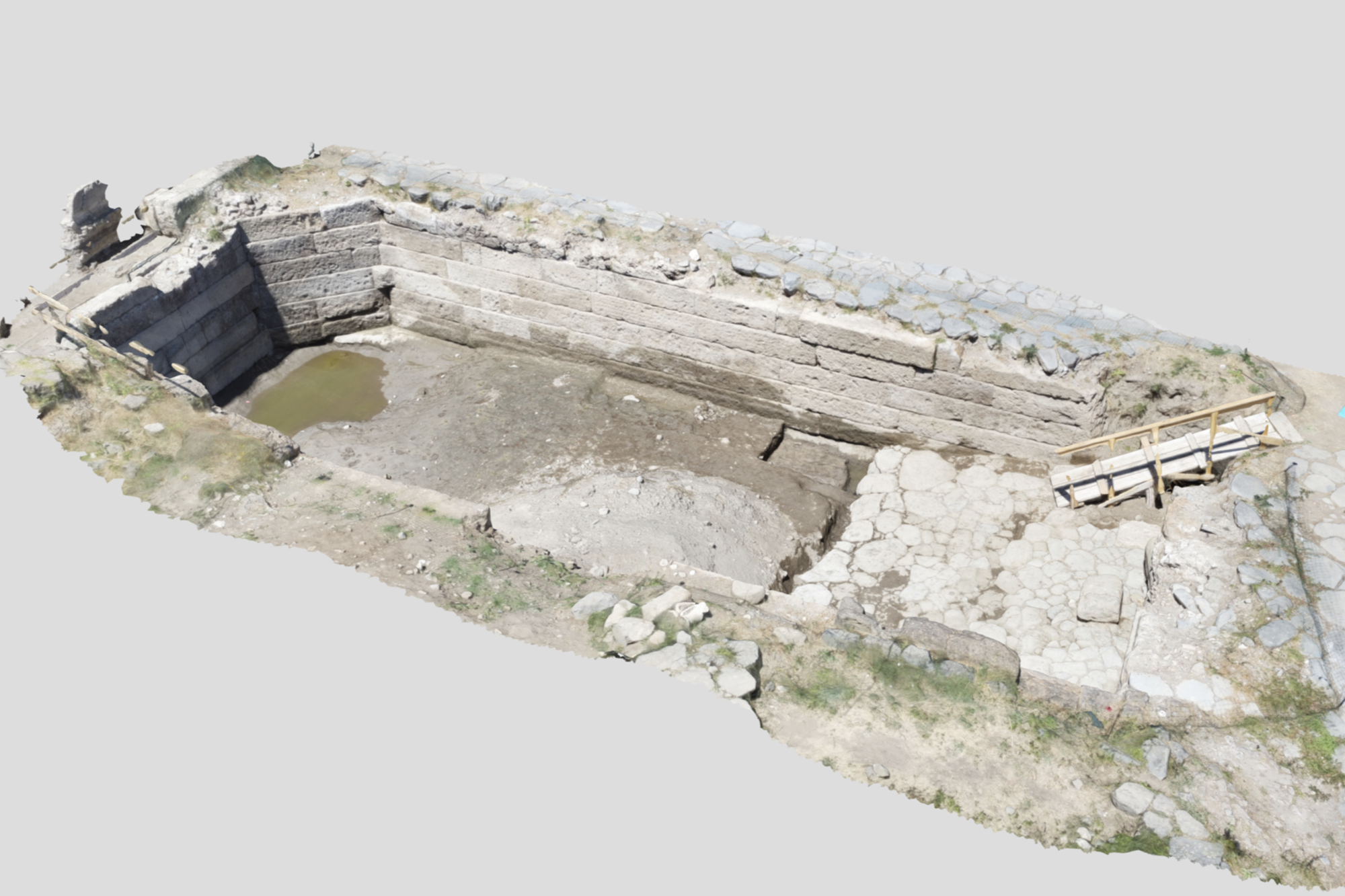

In the heart of the ancient Roman city of Gabii, located just 11 miles east of Rome, a team of archaeologists led by University of Missouri professor Marcello Mogetta has made a remarkable discovery: the remains of a massive stone-lined basin, partly carved directly into the bedrock.

Built around 250 B.C., with evidence that some parts may be even older, this man-made structure may be one of the earliest examples of Roman monumental architecture other than temples and city walls.

Mogetta, the chair of Mizzou’s Department of Classics, Archaeology and Religion, said monumental architecture is about more than realism — it’s also a powerful tool for political expression.

“This discovery gives us a rare look at how the early Romans experimented with city planning,” he said. “Its location — at the center of the city near the main crossroads — suggests it may have been a monumental pool that was part of the city’s forum, or the heart of public life in Roman towns. Since archaeologists still don’t fully know what the early Roman Forum truly looked like, Gabii provides an invaluable window into its development.”

The finding builds on the team’s earlier work at Gabii, including the “Area F Building,” a terraced complex carved into the slope of the ancient volcanic crater around which the city grew.

Together, these discoveries show how Roman builders were inspired by Greek architecture. From the Parthenon to the Agora, the Greeks created paved plazas, dramatic terraces and grand civic spaces that were as much about image and power as function — lessons the early Romans adapted for their own cities.

What’s next

Gabii occupies a special place in Roman history.

“While Rome’s earliest layers were buried beneath centuries of later construction, Gabii — a once-powerful neighbor and rival of Rome, first settled in the Early Iron Age — was largely abandoned by 50 B.C. and later reoccupied on a much smaller scale,” Mogetta, whose appointment is in Mizzou’s College of Arts and Science, said. “Because of this, Gabii’s original streets and building foundations are unusually well preserved, offering a rare glimpse into early Roman life.”

Recognizing the historical and cultural significance of the ancient city, Italy’s Ministry of Culture established Gabii as an archaeological park — now part of an autonomous institute, the Musei e Parchi Archeologici di Praeneste e Gabii. This designation has allowed researchers, including an international venture called the Gabii Project, to carefully explore and excavate the site. Last year, Mogetta became the research group’s new director.

Next summer, with support from the General Directorate of Museums in Italy, Gabii Project archaeologists will continue excavating what has accumulated in the basin over time and the area around it — featuring a large stone-paved area. In the future, they also plan to investigate a mysterious “anomaly” near the basin site. Initially revealed through thermal imaging scans, it could possibly be a temple or another type of large civic building.

“If it’s a temple, it could help us explain some of the artifacts we’ve already found in the abandonment levels of the basin, such as intact vessels, lamps, perfume containers and cups inscribed with unusual markings,” Mogetta said. “Some of these objects may have been deliberately placed there as religious offerings or discarded in connection with the ritual closing of the pool around 50 C.E. — thus underscoring the crucial role played by water management in ancient cities.”

The Gabii Project’s ongoing work helps ensure the city’s ancient history is preserved, studied and shared with visitors for generations to come.

One key question remains: whether civic spaces emerged before religious centers, or vice versa. What researchers find could help reveal whether politics or worship played a larger role in shaping the Roman people’s earliest monumental landscapes.

By piecing together these clues, Mogetta and his team hope to reconstruct not only the story of Gabii — how it grew, flourished and eventually vanished — but also the deeper story of Roman architecture and its influence on the modern world.