February 12, 2025

Contact: Brian Consiglio, consigliob@missouri.edu

Photos by Ben Stewart

Our cells constantly receive DNA damage from factors such as ultraviolet rays, irradiations, toxins and chemicals. For women, that can lead to poor egg quality, which in turn can cause infertility, miscarriage, birth defects or genetic disorders.

Researchers at the University of Missouri are now working to better understand a process that can help repair that damage.

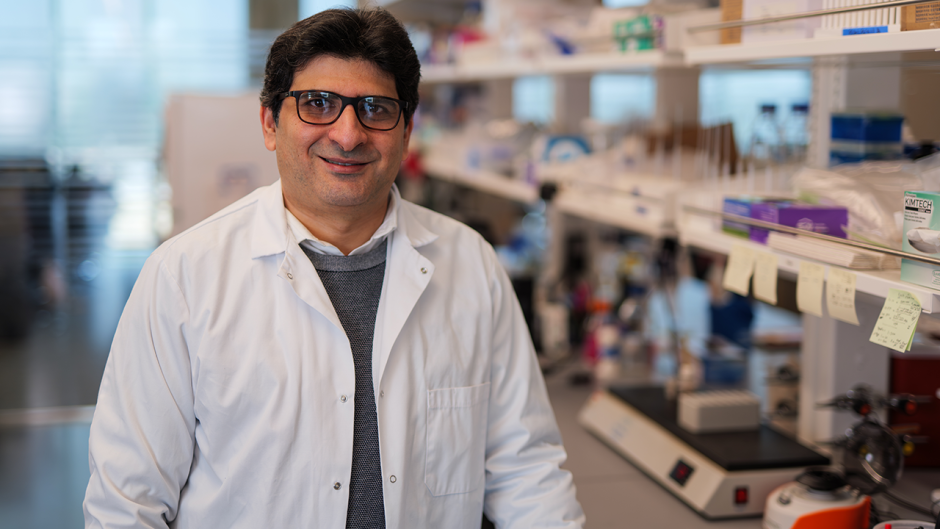

In a recent study, a team led by Ahmed Balboula, an assistant professor in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources (CAFNR) and researcher at the Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building, is studying a process known as autophagy. The unsung hero of cellular biology, autophagy serves as the body’s natural defense mechanism, maintaining cellular health by recycling components, ensuring the body's systems stay balanced and functional.

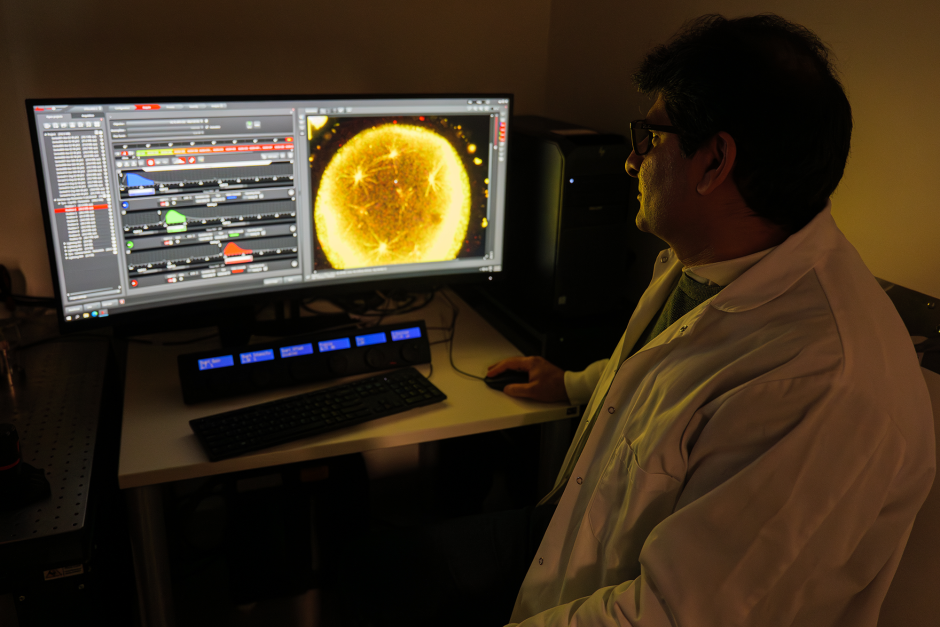

But in Balboula’s recent study, his research team discovered that in female eggs, autophagy is less efficient when there is moderate or severe DNA damage, which is more common in older women.

“When autophagy activity decreases in DNA-damaged eggs or in maternally aged eggs, which have moderate DNA damage, there is an increased risk for aneuploidy,” Balboula said. “Aneuploidy — an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell — is the leading genetic cause of miscarriage and congenital birth defects, including Down syndrome.”

Balboula and his team also discovered a possible solution. In the study, they found that by boosting or stimulating the process of autophagy in female eggs, they were able to improve egg quality by reducing DNA damage and the likelihood of abnormal chromosome numbers.

By successfully showing that stimulating autophagy can reduce the levels of DNA damage in female eggs, the findings can open up new directions for improving the quality of female eggs, ultimately improving reproductive health for both humans and animals.

“The deactivation of autophagy that we found is likely just one of many underlying mechanisms contributing to aneuploidy,” Balboula said. “Going forward, I will continue to explore other underlying mechanisms contributing to poor egg quality to ultimately further efforts to improve the quality of female eggs.”

Balboula came to Mizzou from the University of Cambridge in 2019 because of its strong reputation as a leader in reproductive biology research.

“I knew this was the place to enhance my career,” he said. “The collaborators, resources and research infrastructure here at Mizzou, especially within CAFNR, the Division of Animal Sciences and the NextGen Precision Health building, help us take our research to the next level, and we are just getting started.”

“Increased DNA damage in full-grown oocytes is correlated with diminished autophagy activation” was published in Nature Communications. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.