Published on Show Me Mizzou April 24, 2025

Story by Chris Blose, MA ’04

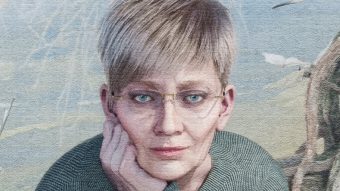

Kelsie lensing is still discovering the full range of what practitioners in her chosen profession do to serve patients. The second-year graduate student in speech, language and hearing sciences has already packed a world of perspective into a career that’s just beginning.

She has worked with a variety of clients, including school-age children who have difficulty with articulation, language and reading challenges. She’s helped non-native English speakers improve their confidence and conversational skills. She’s aided adults who have cognition and swallowing disorders to retrain their muscles and learn new techniques for this critical life skill that most of us take for granted. “Our scope of practice is so much bigger than what most people think,” Lensing says.

Lensing knows this because she actually gets to train in that scope of practice at Mizzou, through the College of Health Sciences’ numerous hands-on clinics and other educational experiences. In these settings, students in physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech-language pathology, social work and other disciplines get something no textbook or theory can properly prepare them for: face time with real humans, each of whom comes with their own needs and idiosyncrasies.

“I think building rapport is the biggest challenge once you actually have a patient sitting in front of you,” Lensing says. “But that is the thing I love.”

Such experience comes by design, says Lea Ann Lowery, BHS ’88, M Ed ’03, OTD, clinical professor and faculty fellow for interprofessional education. Lowery, who graduated from the college and has been on faculty for 21 years, creates

interprofessional events for students to gain practice. She started the college’s first occupational therapy clinic, based on her own experience and understanding of what students need to learn beyond the classroom.

“Classwork is important, of course,” Lowery says. “But we can’t just study paper cases. Paper cases, they get well all the time. They do so well. They’re always cooperative and do everything you ask them to do. But real people are complex. I can’t teach the complexity of people. You have to work with people to wrap your head around it.”

The Missouri Method for health

Lowery recalls her time as an occupational therapy student at Mizzou. The program was in transition at the time and had lost some of its full-time faculty, so the college brought in practicing clinicians to teach.

Instead of feeling like a temporary solution, it felt like a gift. “These were people who came in and said, ‘This is what practice is really like,’” Lowery says.

As a practicing clinician above all else, Lowery carried that experience with her when she joined the faculty as an educator. Lowery and colleagues have made clinical experience a cornerstone of a College of Health Sciences education, with practical knowledge intricately tied to classroom learning.

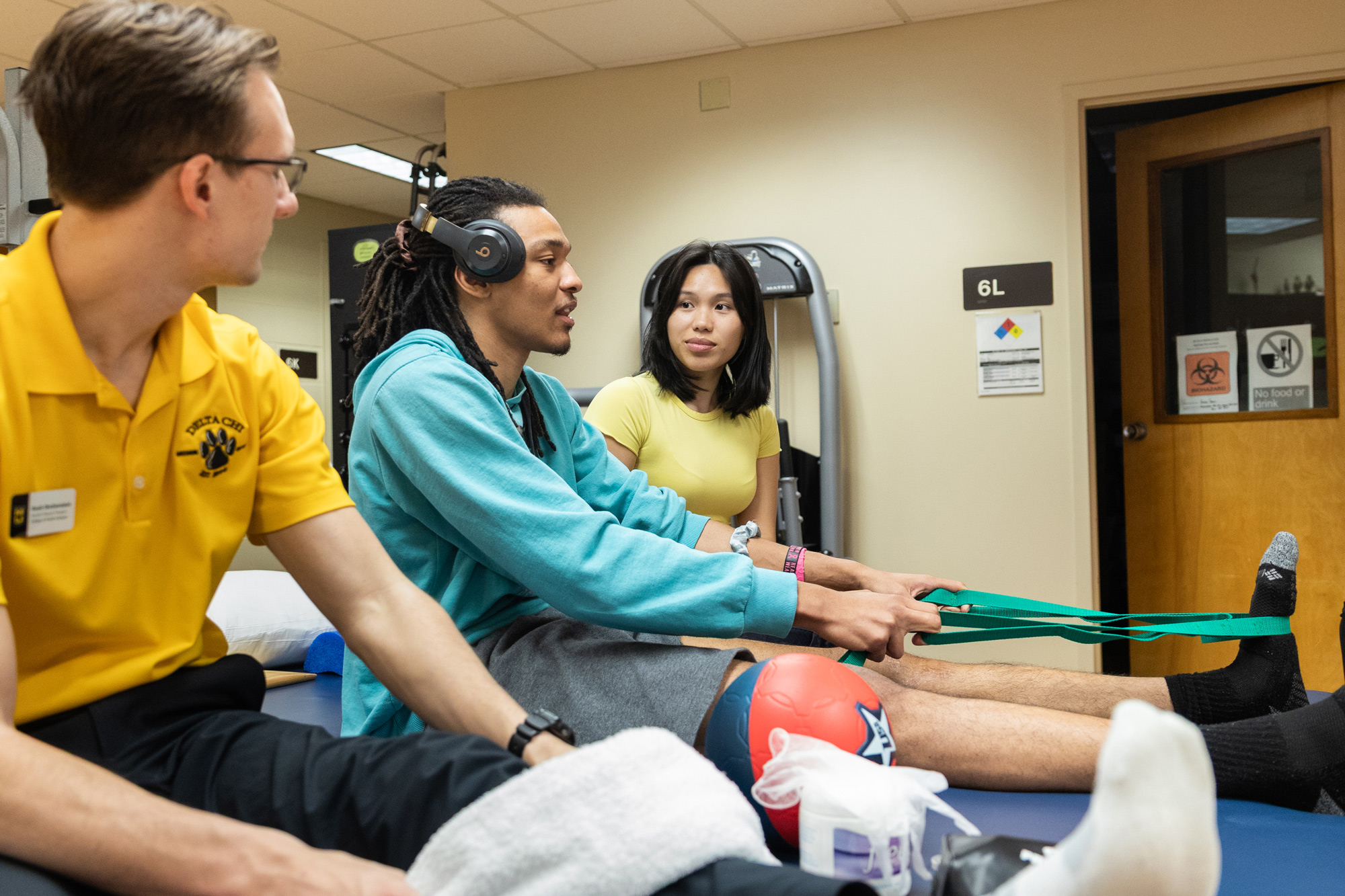

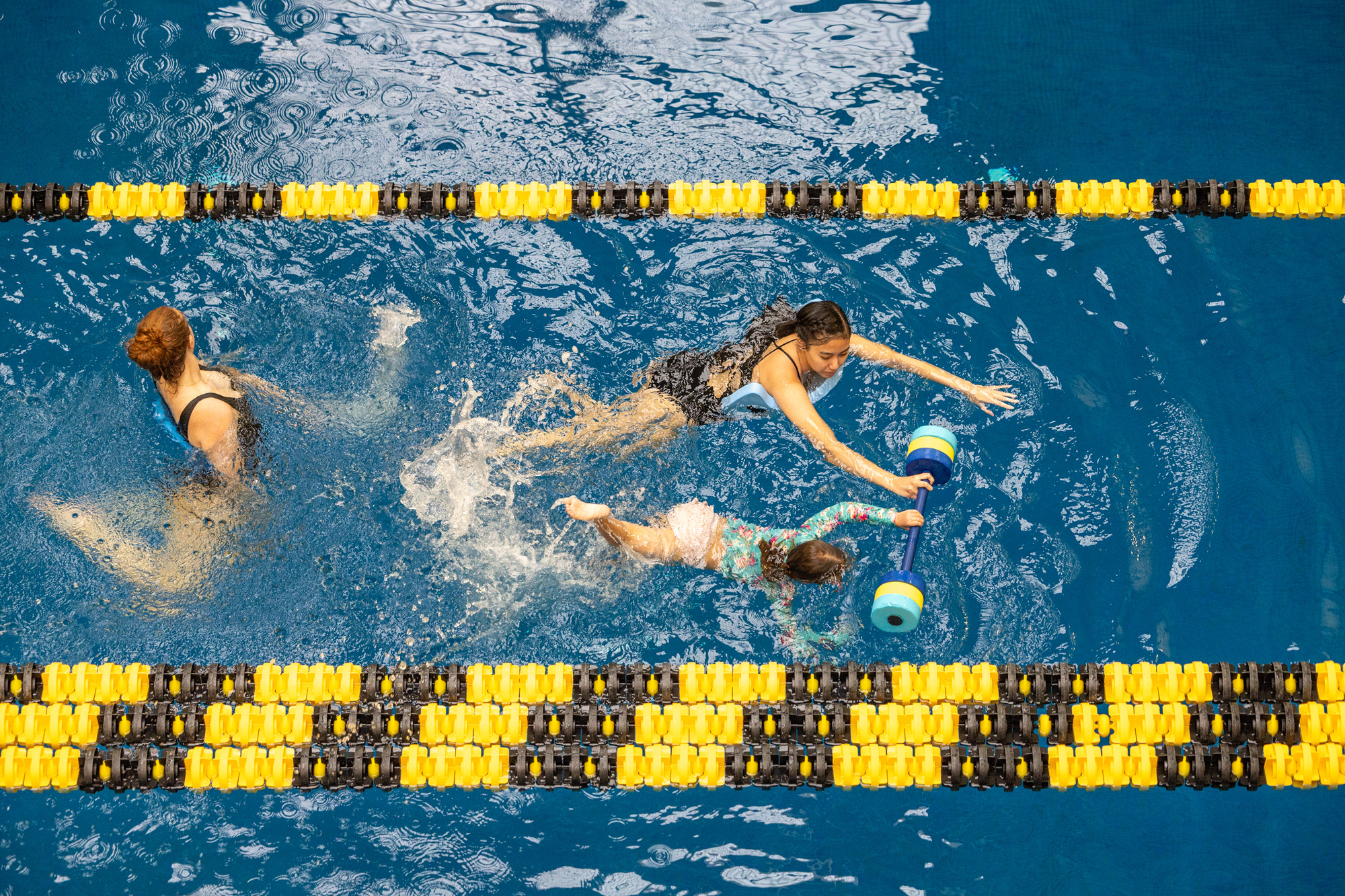

Since 2000, those clinical experiences have expanded greatly. For instance, students in occupational therapy work with patients in both an outpatient clinical setting and out in the surrounding community. Through Tiger OT, students gain experience interacting with patients and solving clinical problems for both children and adults who come in with a range of issues, from neurological and musculoskeletal conditions to developmental issues.

Similarly, aspiring physical therapists gain practical experience through PhysZOU, a pro bono clinic that not only gives these students face-to-face time with patients but also serves a distinct community role by providing therapy to the underinsured and uninsured. Speech, language and hearing sciences students like Lensing often get their first experience with adult and pediatric patients via the on-campus MU Speech and Hearing Clinic, or at the Combs Language Preschool, which serves young children with language difficulties. School of Social Work students practice real and often life-changing therapy at the Integrative Behavioral Health Clinic. Under faculty supervision, psychology interns and post-doctoral fellows provide assessment and consultation services to address concerns ranging from traumatic brain injury to neurodevelopmental disorders through Department of Health Psychology adult and pediatric neuropsychology clinics.

Students get the benefit of real-world practice, and in turn, patients get the benefit of professional services, many conveniently located directly on campus in Lewis and Clark Hall or nearby. For instance, a client at the MU Speech and Hearing Clinic may also get referred to Tiger OT or PhysZou, with a social work student acting as case manager and care coordinator.

The model has evolved to the point where each subset of College of Health Sciences students has a chance to do the work before they graduate — and to connect that practical learning to coursework. What’s even more important to Lowery, though, is when those different types of clinicians have a chance to do the work together.

There are plenty of evolving examples of this, such as Mizzou’s Child Development Lab, housed under the College of Education and Human Development. The lab offers burgeoning PTs, OTs and SLPs the opportunity to practice pediatric services in a multidisciplinary environment.

But the prime interprofessional model is a program that’s close to Lowery’s heart, TIPS for Kids in the Thompson Center for Autism and Neurodevelopment. TIPS stands for Training in Interdisciplinary Partnerships and Services, and that’s exactly what the program provides, both in didactic and clinical programming. TIPS training lasts a year and offers complete immersion for postdoctoral and advanced graduate students specializing in neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly autism. It includes a range of clinician and nonclinician types: OTs, PTs, SLPs, psychologists, social workers, family advocates, you name it.

Visits with TIPS patients and their families are often revealing. “After our clients come in, then we do some debriefing as a group,” Lowery says. “Let’s talk about the family that came today. What were some initial ideas or thoughts that you had based on the information that you received? What did you discover that surprised you? What are some new ways that you can appreciate this family’s situation?”

Early in the program, visits are a way for students to uncover their own assumptions and behavioral biases, then work on them to improve patient interaction and care. As the program progresses, the next valuable lesson often comes from interaction with other professionals. After all, in the real world, clinicians don’t work in isolation. They interact with orders and notes from various other caregivers, from doctors and nurses to pharmacists.

“It can be pretty overwhelming whenever you’re first in a clinical situation,” Lowery says. “It’s a new language, and each discipline has their own language. Immersing yourself in that and interacting with people who are speaking different languages helps you put together the whole picture for patients.”

The care team

On a December day in 2024, all the College of Health Sciences’ clinical education philosophies came to life in one place at the Woodhaven community.

In a carefully organized flow designed by students, Woodhaven’s residents — adults with developmental disabilities — moved from clinical station to station. Here, physical therapy

students assessed their mobility, balance and flexibility. Over there, speech, language and hearing sciences students conversed with them to analyze any challenges with articulation, language, swallowing or other needs. At another station, occupational therapy students performed diagnostics on everything from motor skills to sensory processing.

Lowery, who serves on the board at Woodhaven, and fellow faculty Cody Higgins and Kelly Stephens launched this pilot not only to increase the interprofessional opportunities for students but also to aid a population that tends to fall through the cracks. Such pilots are common at the college.

“We try things,” Lowery says. “We assess the results. And if it works, we do more of it.”

From the perspective of Lensing, who took part in the Woodhaven pilot, these programs certainly do work. “I think they do an amazing job of getting us exposed to clients right away,” Lensing says.

Most recently, Lensing has been working an internship in an adult rehabilitation clinic in Florida. She says her experience in past clinical settings helped prepare her for what it’s really like to work as part of a care team.

“We have PTs and OTs in the clinic,” she says. “Many of my speech patients see one of them right after their session with me. I can then share the communication strategies I used with the patient and their effectiveness. I think it’s important to be able to track a patient’s progress across their entire therapy journey.”

She also has learned how to tackle that first challenge of building rapport — and how the approach varies depending on the type of patient. Children often want to play, so a playful, game-like approach can help a clinician hook them into therapy. Many adults, on the other hand, react best to someone who has a deep and meaningful conversation with them.

Ultimately, it’s about learning to recognize, analyze and treat each patient as an individual. “Using my educational background to make those clinical decisions,” Lensing says, “it’s not as easy as following a set of steps and expecting results. You really have to analyze that person. And I think that’s something that really develops throughout our clinical experience.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.