October 9, 2025

Contact: Brian Consiglio, consigliob@missouri.edu

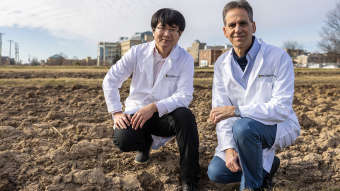

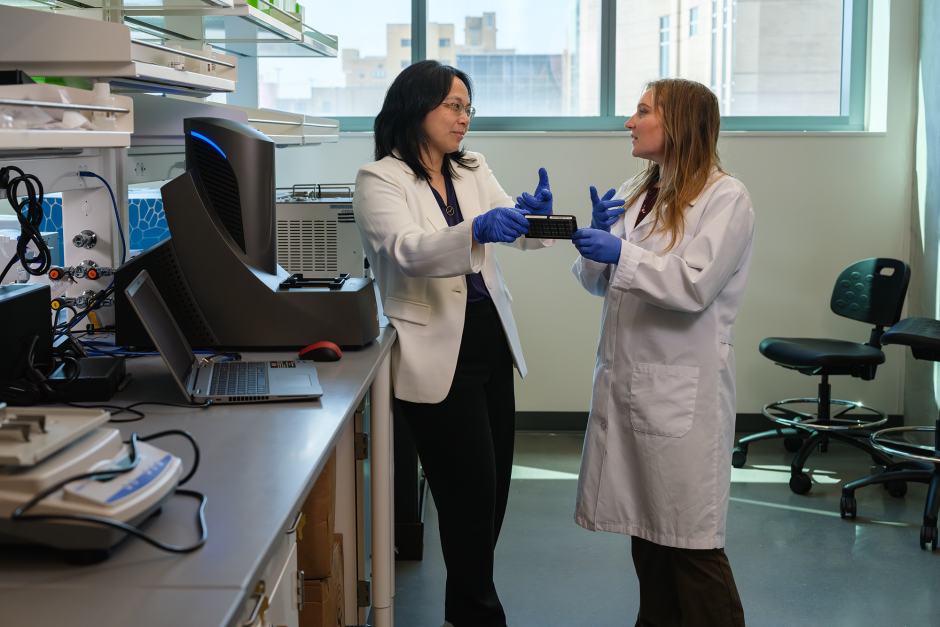

Photo by Harper Snyder

There may be a way to protect brain energy to preserve cognition — and the secret could lie on your plate. Think fish and seafood, meat, non-starchy vegetables, berries, nuts, seeds, eggs and even high-fat dairy products.

University of Missouri researchers are now testing just how powerful these foods can be. They’ve found that a high fat, low carb diet — known as the ketogenic diet — may not only preserve brain health but also stop or slow the signs of cognitive decline for those at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

In the Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building, Ai-Ling Lin, a professor in the School of Medicine, and doctoral student Kira Ivanich are studying whether a ketogenic diet can be particularly helpful for those born with the APOE4 gene, the strongest known genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

In a recent study involving mice, they found that females with the APOE4 gene had healthier gut bacteria and more brain energy while eating a ketogenic diet compared to a control group eating a higher-carb diet. While males did not see these same improvements, the study offers insight into who may benefit the most from eating a ketogenic diet.

That’s because the diet changes how the brain fuels itself.

“When we eat carbs, our brains convert the glucose into fuel for our brains, but those with the APOE4 gene — particularly females — struggle to convert the glucose into brain energy, and this can lead to cognitive decline down the road,” Ivanich said. “By switching to a keto diet, ketones are produced and used as an alternative fuel source. This may decrease the chance of developing Alzheimer’s by preserving the health of brain cells.”

The results highlight the importance of precision nutrition — tailoring diets and interventions to those who would benefit most.

“Instead of expecting one solution to work for everyone, it might be better to consider a variety of factors, including someone’s genotype, gut microbiome, gender and age,” Lin said. “Since the symptoms of Alzheimer’s — which tend to be irreversible once they start — usually appear after age 65, the time to be thinking about preserving brain health is well before then, so hopefully our research can offer hope to many people through early interventions.”

Lin came to Mizzou for interdisciplinary collaboration and the state-of-the-art imaging equipment in the NextGen Precision Health building and at the University of Missouri Research Reactor.

“We can do a lot of things in-house here that at other places we would have to outsource,” Lin said. “This is team science. The impact we make will be much better when we work together than by ourselves.”

With cutting-edge imaging equipment and both research and clinical spaces under the same roof, the NextGen Precision Health building allows Mizzou to move quickly from preclinical models to human trials.

For Ivanich, that real-world impact is personal.

“When my grandmother got Alzheimer’s, that sparked my interest in this topic, so being able to make an impact to help people preserve their brain health is very rewarding,” she said. “With Mizzou being a leading research university and having a tight-knit community feel, I know I’m at the right place.”

“Ketogenic diet modulates gut microbiota-brain metabolite axis in a sex-and genotype-specific manner in APOE4 mice” was published in the Journal of Neurochemistry.