Nov. 20, 2024

Contact: Janese Heavin, heavinj@missouri.edu

Photos by Abbie Lankitus

Americans love their corn — whether it’s canned, fresh off the cob or in their favorite breakfast cereal.

But what if this staple grain could be more than just a starch? What if it could become a critical source of protein and fiber while helping prevent cancer, obesity, diabetes and inflammation?

It can, University of Missouri researchers say. And the secret is in the color.

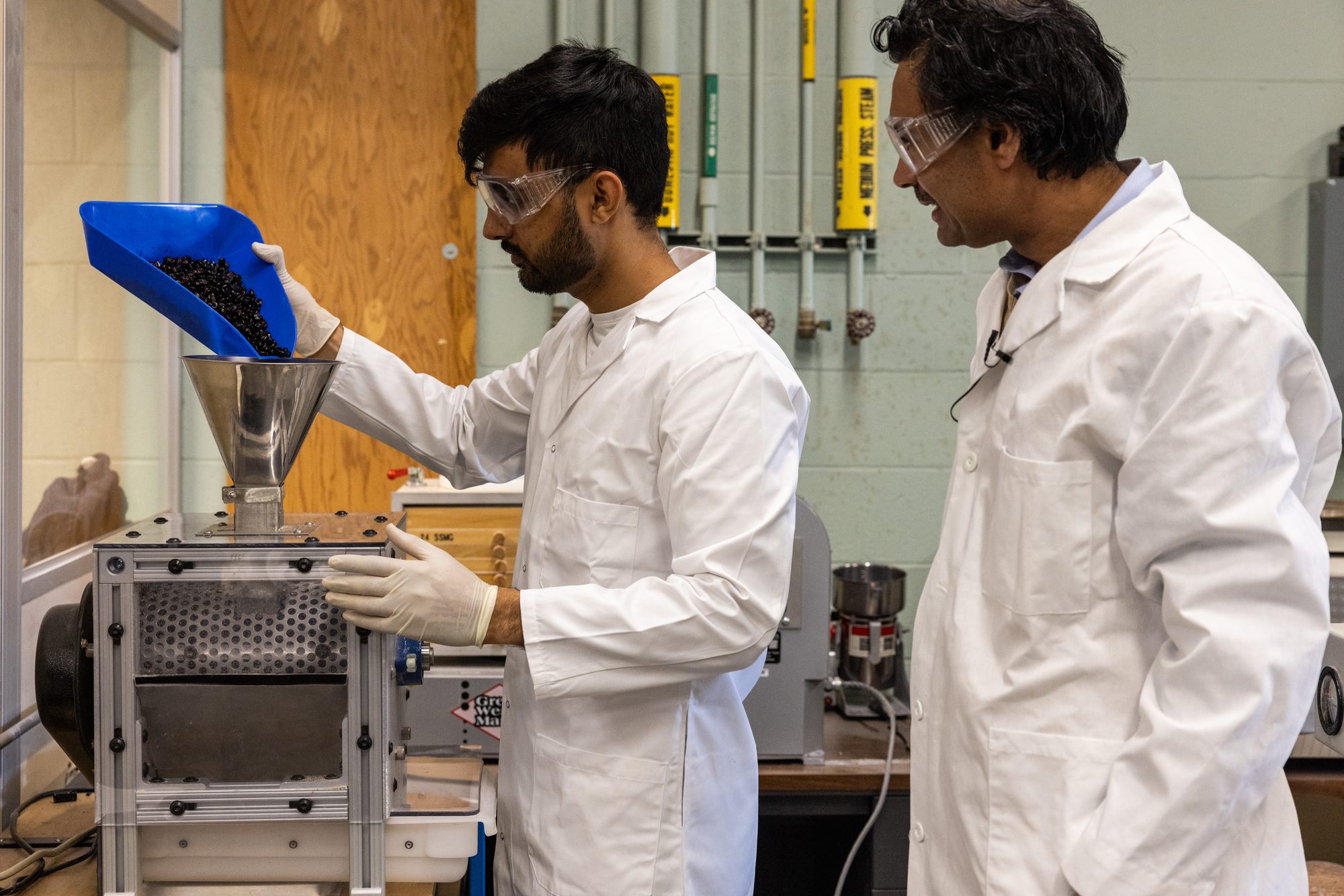

Assistant Professor Pavel Somavat and his team are analyzing dozens of varieties of corn, comparing the nutritional properties of blue, red and purple maize to traditional yellow dent corn.

They’re working with Sherry Flint-Garcia, a research geneticist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service who studies heirloom corn at Mizzou’s South Farm.

For the past three years, she’s also grown different varieties of colored corn for Somavat’s work.

“We’re identifying the best varieties and providing feedback she uses to decide which varieties to breed for the next cycle,” said Somavat, who has joint appointments in Mizzou’s College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources and the College of Engineering. “We’re looking at the make-up of the corn and how it responds to Midwestern climates, as well as how we can add value to the corn by developing new uses for it.”

A dark purple corn, known as Maiz Morado and found in South America, is proving to be the healthiest. The corn itself is edible, and the outer layer of the kernels contains more antioxidants than found in blueberries, as well as flavonoids, phenolic acids, tannins and other beneficial chemicals that can easily be extracted for other novel applications in the food industry, adding value to the crop.

Right now, though, Maiz Morado doesn’t grow well in Missouri’s climate, Flint-Garcia said. Throughout the project, she’s had to repeatedly cross Maiz Morado with yellow corn to create pure breeding temperate adapted lines. Then she will cross these pure breeding lines to create hybrids that produce full-sized purple ears of corn. It will take additional work to ensure the corn yield is high enough to turn a profit.

Adding value

Missouri is already a top producer of corn in the U.S. Somavat believes there are opportunities to expand production into new markets, diversifying revenue streams for farmers.

While consumers might need time to adjust to the idea of eating purple corn, there are other ways to incorporate the health benefits of non-traditional corn varieties into our food supply.

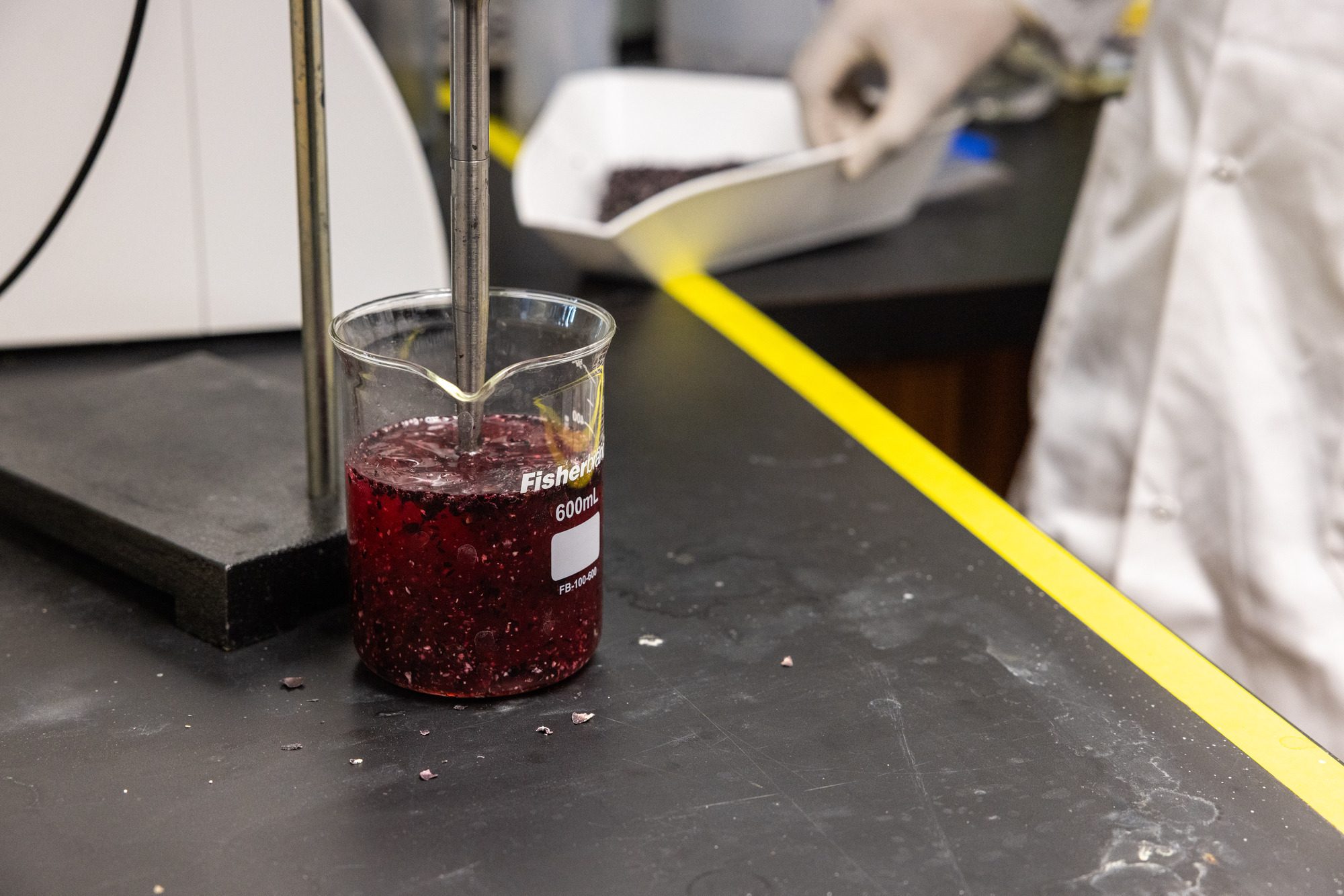

One of the most promising uses is as a food dye.

Extracts from purple corn, for instance, could replace Red Dye 40, a petroleum-based synthetic dye found in many foods, including dairy products, sweets and beverages. While the Food and Drug Administration has deemed it safe for human consumption, studies have linked Red Dye 40 to migraines, allergic reactions and even attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In response, California recently passed a law banning red and other synthetic dyes from meals and drinks served in public schools.

By replacing synthetic dyes with natural extracts from colored corn, food products could be both safer and more nutritious.

Researchers are also finding ways to utilize the plant proteins and phytochemicals extracted from purple corn biomass — parts of the plant typically discarded — converting them into a waxy packaging material that has antimicrobial properties. The material, which could be used instead of plastic wrap, not only keeps food safe but is also edible and biodegradable.

Somavat’s team even explored the insect-repellent properties of pigments and phytochemical compounds from different colored corn varieties. Early findings suggest that the chemicals found in purple corn could be extracted and used as a natural pest deterrent for high-value fruits and vegetables grown in greenhouses and organic farms.

“The potential of non-yellow corn goes far beyond food,” Somavat said. “With its unique health benefits and other applications, it offers a sustainable, high-value alternative for farmers and consumers alike. This is allowing us to rethink the role of corn in our future.”

Somavat and collaborators recently published their findings on adaptation and pigment/phytochemical contents of Missouri-grown colored corn varieties for value-added products in the journal Industrial Crops and Products. Co-authors were Mizzou’s Ravinder Kumar, Joseph Agliata, Caixia Wan, Azlin Mustapha, Jiayue Cheng, Miriam Nancy Salazar-Vidal and Flint-Garcia, who has an adjunct appointment.