Published on Show Me Mizzou April 30, 2024

Story by Dale Smith, BJ ’88

Google Earth and other high-flying technologies allow us to view the deepest reaches of the Amazon River Basin, an area that remains home to indigenous people who live as their ancestors have for thousands of years. Scholars of rainforest ways, they hunt, gather and grow their own food in the severe terrain at the Amazon headwaters with no regard for the satellite eye above. They heal themselves with medicines culled from their surroundings; shelter and clothe themselves with local material; and protect themselves with weapons of their own devising.

Mizzou researcher Rob Walker calls them “the most traditional humans on the planet, living remnants of human life before the dawn of agriculture, the first guardians of the forest. Yet what we see now is just a tiny sliver remaining who are still uncontacted.”

Before Europeans arrived in 1500, Amazonia had thousands of tribes with populations in the low millions, says Walker, associate professor of anthropology. But since that initial contact, epidemics — first smallpox and measles, lately COVID — have decimated indigenous populations. Early exploitation, including slavery, largely has given way to the occasional fatal conflict with illegal gold miners and loggers, as well as drug runners and others who impose themselves on tribal lands.

Walker’s new research looks at satellite images spanning more than two decades to track whether populations are growing under controversial government no-contact policies. “This approach says the tribes have survived for thousands of years, so, ‘Let them do them, and they’ll be fine.’ But that’s difficult to say, as they are in close proximity to people who don’t wish them well.”

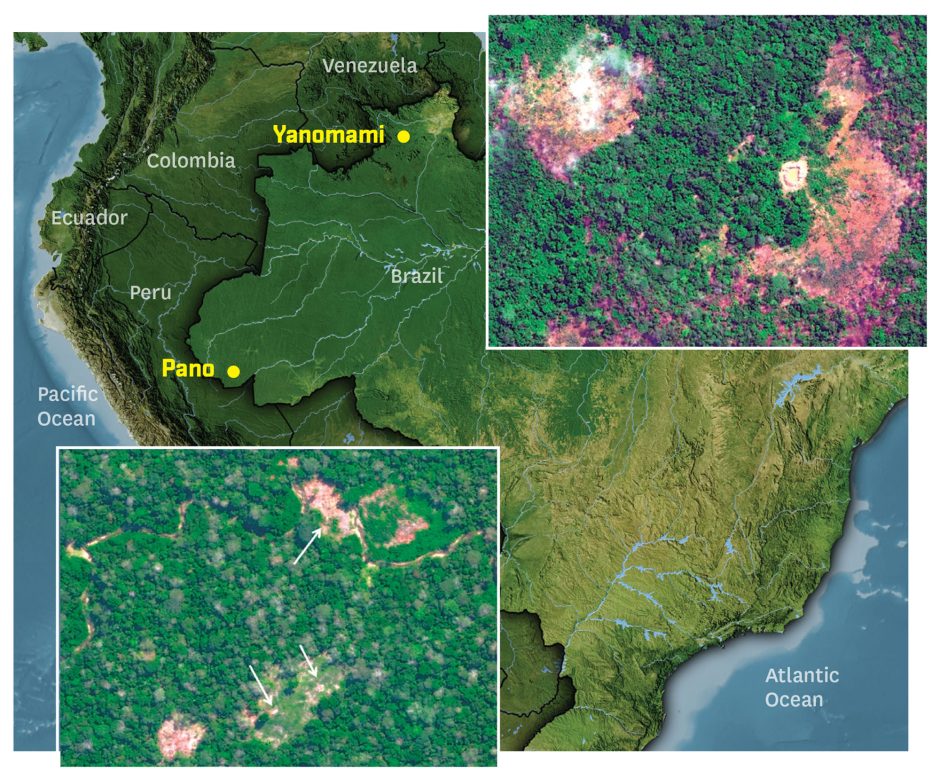

Of the roughly 30 uncontacted tribes in the Amazon Basin, Walker’s study follows the two largest, named here for their language family: Pano and Yanomami. Satellite photos reveal not only large-scale deforestation from logging and mining but also village-scale alterations in the landscape. Walker analyzed the number of village buildings and the area of each hut’s roof. Judging by their similarity and other clues, he suspects the tribes have egalitarian social structures.

Both groups supplement their hunting and gathering with slash-and-burn agriculture, in which they cut down vegetation and set it ablaze to clear land for crops. Walker uses software that measures the fields and detects smoke from the fires. Growing primarily sweet manioc, a root vegetable, or plantains for three to five years exhausts the soil, and then the tribes start anew at another site. Within about seven years, the forest reclaims the previously used land.

Most successful are the uncontacted Pano, whose population Walker estimates at 500 to 1,000. Since 2001, land they’ve cleared for gardens has expanded rapidly, averaging greater than 10 percent annual increases as the tribe has grown from two clusters of villages to four.

He is encouraged by such “fissioning” of groups. “Populations are more resilient if they split into subpopulations with gene flow across them as people seek mates in different villages.” There’s also strength in numbers. The Pano now have so many warriors that neighbors offer gifts of machetes, axes and even gardens to remain in their good graces.

The uncontacted Yanomami, at a population of about 100, also appear to be trending up, as their village recently doubled to two clusters.

But Walker is worried about the other 28 tribes. “They are small, nomadic and hard to track. They don’t make the clearings our satellite images can spot. Most of what we know about them is through accidental contacts.” One such group in Peru appears robust, judging by its bold raids on other tribes. However, Walker suspects most tribes live near the edge of extinction. “I would hesitate to say we should leave them uncontacted. Without medical care, protection and other assistance, in 20 years they may have blinked out.”

Walker’s sky-level research dovetails with on-the-ground reporting such as that detailed by Scott Wallace, MA ’83, in his bestselling book, The Unconquered: In Search of the Amazon’s Last Uncontacted Tribes (Crown Publishing, 2011).

“Satellite images are instrumental in leading concerned people, including real efforts by governments, to confirm the presence of isolated groups,” says Wallace, associate professor of journalism at the University of Connecticut. With that information, governments can make policies to protect land from the likes of illegal miners and track threats such as logging and ranching that intrude into tribal territories.

Most people consider uncontacted tribes — if they consider them at all — to be exotic curiosities, Wallace says. “Perhaps their biggest value to the wider world is to fire imaginations about what 99 percent of human history was like before agriculture and the industrial revolution. With intact forest and clean water, they sustain themselves in a harsh environment. They help us recognize the importance of respecting people and their wishes to pursue a way of life as they know it.”

More: Read Walker’s article at mizzou.us/naturewalker

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.