Published on Show Me Mizzou Aug. 27, 2024

Story By Nina Mukerjee Furstenau, BJ ’84

Photos by Abbie Lankitus and Sam O’Keefe, BJ ’09, MA ’24

Mushroom hunting in Missouri isn’t always easy pickings. All eyes need to be aimed at the ground, and a search requires patience and a knack for wandering. Sometimes even a fruitless hunt is more than worth the effort.

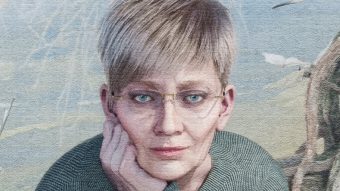

“There’s always something to discover,” says Malissa Briggler, Missouri State Botanist and leader of the mid-Missouri chapter of the Mycological Society, as she hunts near her New Bloomfield, Missouri home, along with a reporting team from KBIA’s Canned Peaches podcast consisting of students from the Missouri School of Journalism. Today they’re looking for chanterelles, which remain hidden despite the group’s best efforts. Still, they make many discoveries while spending time in the woods.

“I mean, I did run into like three spiderwebs and got ticks,” producer Lauren Hines-Acosta, BJ ’23, says wryly. Despite these tiny traumas, the pursuit of mushrooms reveals a world we often miss or forget to notice.

“We’re so busy and connected,” Briggler says, adding that mushroom hunting requires slowness. “We disconnect to connect.”

Mushrooms, part of the fungi kingdom like lichens, yeasts and molds, are not like other plants or animals. They’re the fruiting body of an undergrown network of mycelium, for one. Perhaps because of this subterranean growth, fungi in folklore often have mystic and transformative powers. Think of the red-capped fly agaric mushroom in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Alice nibbles on one side to grow taller and the other side to shrink. In Ireland, they’re linked to faeries and leprechauns. For many ancients, because of the mushroom’s underground connection to a much larger, very old, organism, its wisdom could be passed to humans via consumption.

What a culture thinks of mushrooms has a lot to do with how it feels about magic — whether it’s a dark force or a benevolent one — and the era. Today, mushroom fever is spreading for more than mere mystique. Taste and versatility in diets, especially in plant-forward eating that might just save our planet, along with the role they can play in carbon sequestration and their amazing talent for pollutant filtering, adds up to a global shroom boom.

Network communication

Like Briggler, more and more researchers are discovering the mushroom’s ability to make connections. Forest ecologist Susan Simard, who spoke earlier this year at the University of Missouri’s William A. Albrecht Lectureship at the Bond Life Sciences Center, has been fascinated for most of her career. She discussed hub or “mother” trees in forests and how below-ground fungal networks link a forest community. A pioneer in plant communication and intelligence, Simard says survival of the fittest means something different in a forest, where plants collaborate as a community.

“In one forest example of a 100’ x 100’ area,” Simard says, “there are (typically) 300 species of mycorrhizal fungi and all the trees are connected by it underground. The big trees are the most highly connected. These are the hub, or mother, trees.”

But in her home region of British Columbia, clear-cut logging has destroyed all but two to three percent of the big tree ecosystems. In a clear-cut area, only about six of 300 fungi species survive, and those are reliant on whatever native plants might remain. “It takes a while to recover — 50 to 80 years,” Simard says. “Some of these microbial fungi only grow with old trees.”

In Indigenous cultures, which Simard also studies, “these old trees are known,” she says, and through mycorrhizal networks young and old trees communicate and pass carbon to each other. “It’s all about connection.”

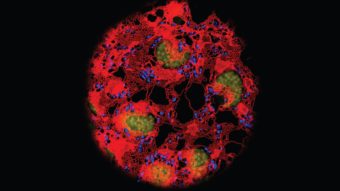

The symbiosis between plants and members of an ancient phylum of fungi (arbuscular mycorrhiza, or AM) suggests a secret society. But these AM fungi connect with 80 percent of plants and help them access distant water and nutrients. They can help plants adapt to environmental change by bringing minerals to where they are. Community and connection once again. They can do more — and here’s where the secret handshake comes in — such as relocating five percent to 20 percent of photosynthates (simple sugars made from once green leaves that feed the plants that produced them) from that plant to the surrounding environment.

Logging shiitakes

In a study published in Microbiome in January, Changfeng Jang, among other researchers, discusses a bacterial-fungal-plant symbiosis that drives plant growth and can reduce the need for fertilizers.

Erica Parker, BA ’10, agrees. Parker put her love of mushrooms and other growing things into the creation of Sage Garden. While still at the university, she began saving to buy land, eventually purchased two acres in Boone County and, later, 70 acres (about the area of a large shopping mall) near Prairie Home. Now, among other sustainably raised foods, she has about 300 shiitake logs and offers them — as well as mushroom-based tinctures — fresh every week at the Columbia Farmer’s Market. “Mushrooms are a big passion of mine,” Parker says. She started in 2012 by inoculating two dozen logs with live shiitake spawn. “Shiitake are one of those super potent mushrooms that taste phenomenal and grow easily. They were a win-win.”

Steven Lancey, BA ’17, studied MU classical humanities. He manages the farm, and describes it as a biologically intensive market garden, one inspired by the agricultural practices on a working farm in Sicily, Italy, where he lived after graduation.

“We’re planting kale, chard and collards today,” Lancey says. “We’ll also do spinach and lettuce.” They’ll do this after plowing, forming beds, and laying irrigation lines.

“And we’re all growing the mushrooms,” Parker adds.

Soil brains and mycelium dreams

Though the mushrooms taste great, Parker and Lancey have deeper designs for their spores.

“We inoculate the soil with different mycelium, different fungal strains, to really rev up the microorganism population of our soil. It’ll be interesting to see the results,” Parker says. “We already started trying this in the Hallsville farm and are seeing the benefits.”

One essential benefit: warding off pests. “Resistance of our crops gets naturally built in,” Lancey says. “The soil is living soil, and mushrooms are so much a part of this because of the mycelium network under the ground is communicating

between all the components of the soil and roots.”

All this adds up to what Parker thinks of as a kind of “soil brain.” “It’s the neural network in the soil microorganisms. We use organic practices, but we still have to use different organic products to control certain pests and fungus when it’s getting out of control.” However, Lancey adds, “We’re seeing less need for that.”

The repair of depleting soil is essential to Parker because, she says, “the mycelium network is going to just keep bringing the whole ecosystem back to life.” The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) agrees, declaring in a 2019 study that fungi are critical to soil biodiversity, carbon sequestration and nutrient cycling. Together, plants and fungi capture carbon from the atmosphere to store in the soil for decades, if not centuries. Mushrooms have a role in nontimber forest farming, too. At the university’s Center for Agroforestry, Olga Romanova, technical aid provider, talks about silvopasture — growing trees in pasture for shade — as an opportunity for mushrooms.

“While your trees are growing, you can gain benefit by producing something in the shade of the trees. Mushrooms are one of the things that can be grown in this way.”

Romanova notes other forest farming techniques that help mushrooms include managing growth of trees to create their optimum conditions. “If your purpose is maintaining the forest, thinning [trees] helps nature by speeding up its process. [The thinned] wood can be used for mushroom production.”

Other benefits? “All fungi, not just the edible mushrooms, are part of the forest, and they help to make the ecosystem more sustainable,” Romanova says. “They help to degrade the wood which has fallen and convert it into soil. Fungi are part of the ecosystem and the food chain and definitely play a huge role in decomposition of the organic material. I find them fascinating.”

Fungi have yet another superpower: an ability to degrade various pollutants in the environment. Adding to that positive piece of the environmental puzzle, consider that nature has found a way to deal with plastics and petroleum-based products, pharmaceuticals, oil and even some “forever” chemicals when humans failed to do so. Such byproducts, processed through fungi, can often be made no longer harmful.

If it’s starting to feel like hero-worship, consider that the fungi system can help ecosystem restoration, too, by advancing reforestation in degraded soils.

Umami in the kitchen

“First time we met,” Allen Judy of Heirloom Fungi and Mandy’s Bamboo Kitchen in Excello, Missouri, says of his wife, “Mandy looked at my face and said, ‘You need reishi mushrooms.’”

The Judys, who grow oyster, shiitake, lion’s mane, king oyster, chestnut and reishi mushrooms in a custom-made 1,500 square foot facility near their home, not only cultivate mushrooms but also sell them at the Columbia Farmer’s Market and include them in delightful ways on the menu of their reservation-only restaurant 65 miles north of Columbia. They produce mushrooms for functional health benefits, too. “I had terrible allergies but no longer,” Allen says.

In fact, a teaspoon a day of reishi mushroom tincture traditionally has been used for allergies and lion’s mane taken for neural clarity. Mushrooms, rich in Vitamin B, C, and D, fiber, minerals and protein, are found in diets of many cultures around the world.

“We sell the tinctures at the market because not everyone has the time to make their own at home,” Mandy says. Mostly, though, the Judys sell mushrooms, nearly 100 pounds per week at the Columbia Farmer’s Market alone, in addition to 25 pounds per week Mandy uses for the restaurant.

Aside from the potential usefulness of mushrooms to our planet and human health, for many, umami flavors are the draw. One recent evening at Mandy’s Bamboo Kitchen, which launched in 2017, the menu included oyster mushroom tempura, lion’s mane mushroom “crab” cake and sauteed shiitake and celery, in addition to pan fried dumplings, bacon wrapped shrimp and asparagus, wine- and soy-braised short ribs. Dessert was a delicate Japanese souffle cheesecake. The flavors and textures alone would make a believer out of most diners.

Mandy’s specialty is a fusion of Asian cuisines: Cantonese, where her parents originated; Vietnamese, where she spent her childhood; and Taiwanese, where she lived for 10 years. The result is a palate awash in rich flavors that are somehow light and never feel heavy, due to her skill with mushrooms. She remembers mushrooms and tinctures from her youth, though they often couldn’t afford them. She says mushroom interest in Missouri has really jumped in recent years.

“People around here don’t always know what to do with mushrooms other than button mushrooms you find at the grocery store,” Mandy says. “But they are starting to understand and come back for more.”

Exploring Missouri mushrooms

Missouri’s diverse habitats, including forests, woodlands and wetlands, provide fertile environments for medicinal and culinary mushrooms. Here are some of the state’s most common.

Medicinal mushrooms

Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum)

Known as the “mushroom of immortality,” reishi has a kidney-shaped cap and reddish-brown color. Boosts the immune system, reduces stress, improves sleep and has antiinflammatory properties. Used for allergies.

Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus)

White, globe-shaped fungi with long cascading spines, resembling a lion’s mane. Supports brain health and cognitive function and may help with nerve regeneration.

Maitake (Grifola frondosa)

Also known as “hen of the woods,” maitake forms large clusters with spoon-shaped caps, often found at the base of oak trees. Regulates blood sugar levels, boosts the immune system and supports cardiovascular health.

Culinary Mushrooms

Shiitake (Lentinula edodes)

Brown, umbrella-shaped cap with a white underside, commonly grown on hardwood logs. Rich, earthy flavor. Used in dishes such as sautéed shiitake and celery.

Oyster and King Oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus eryngii)

Oyster mushrooms have a fan-shaped, delicate texture, while king oysters have thick, meaty stems. Versatile. Used in dishes such as oyster mushroom tempura.

Chanterelles (Cantharellus spp.)

Funnel-shaped with wavy edges, bright yellow to orange. Delicate, fruity flavor. Often used in

risottos, pastas and egg dishes.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.