Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 19, 2024

Story by Julie Seabaugh, BJ ’02

Illustrations by Eddie Guy

Live stand-up comedy may be the most difficult and important art form of the 2020s. Consider the parameters: One person, working with a solo mind and mouth, clinging tightly to only the microphone and a mission to make everyone staring back in the room laugh. Sounds like an utter nightmare to most of us. But for those few artists in their element beneath the club spotlight, stand-up is a calling.

Spontaneous laughter delivers doses of good brain-science things: endorphins, serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin. It axes the stress hormone cortisol. Dorks would call it a natural high. It contextualizes our small place in the universe and helps us take ourselves less seriously. Over the past few years, it’s become vital for combatting a certain relentless, unapologetically manufactured onslaught of mistrust, fear, hypocrisy, injustice, all of it. There’s just so damn much.

Comedy helps transform negative emotions — from, say, stunned disbelief to gut-churning horror — into something that can be processed, and maybe possibly overcome. There’s a certain optimism found watching a roomful of strangers with different backgrounds and beliefs, reacting in real time and in unison, laughing for a moment that can never be replicated.

It’s a screencap of humanity, and it happens in venues nightly. Those little commonalities are real. Keep piecing them together and something vaguely resembling hope can start to emerge.

Moms Mabley’s astounding bravery. Richard Pryor’s humanity. Phillis Diller’s pioneering feminism. Comics have dragged society kicking and screaming out of minstrel shows and vaudeville, into comedy clubs, through cable TV channels and now onto YouTube and TikTok. The best stand-ups make audiences laugh — then go home and think. They challenge seemingly engrained beliefs and prejudices. Learning from a variety of perspectives fosters empathy. Whether receiving or extending, we could all use more of it.

As someone who has covered comedy for 20-plus years in outlets including The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter and dozens of now shuttered alternative-weekly papers, I’ve seen the art and popularity evolve while the difficulties of covering it remain. Admittedly, when Chris Rock asked me in the Comedy Store parking lot (just a few days before the Oscar slap) whether his daughter should be a journalist as she intended, there was nervous hesitation.

Whether moderating panels at festivals or watching Bob Odenkirk, post-heart attack, light up on an Upright Citizens Brigade greenroom couch as he described learning to embrace life again, the world never stops being revelatory. Joan Rivers and Carl Reiner talked to me about pushing themselves to creative limits. I’ve covered roasts, deaths and recently moderated a PBS-sponsored event for Jesus Trejo’s Roots of Comedy series. The journalistic experiences have been validating. The legwork hasn’t gotten any easier.

According to industry reports in May from Bloomberg and Pollstar, live comedy ticket sales have surged, with revenues approaching $1 billion in recent years.

Markets are hungry. Performers typically tied up in TV production seek expression (and paychecks) amid strikes and slowdowns. Barriers to entry are cheap and lax. Outlooks are available for every taste.

It’s also a meritocracy where only the funniest survive.

The industry’s current boom arrived as the world entered strange territory. During the pandemic lockdown, comedy programming (think Bo Burnham’s Inside, Sarah Cooper’s lip-syncing Trump videos, anytime Leslie Jordan took to Instagram live) ruled screens as chaos swirled outside. It quieted frantic interior monologues. What comedy fan didn’t dive deep into unexplored archives, reemerging into public life having found a big-name podcast host, rising up-and-comer or undeniable social-media star to follow?

Once venues reopened, there was much more to discover. An immediacy endures in comedy clubs, where all the machinery and external editing of online videos and other media falls silent. Stand-up goes deeper than crowd work and slick specials. The same reheated tricks don’t work in the trenches, where lifers put in the work during multiple sets, night after night, anywhere there’s a stage and a microphone. Film, visual art, even live music — in my experience, no other form of public expression can do the same. For an increasing number of comedy connoisseurs, laughing among in-the-moment human people beats an evening spent doing literally anything online.

Diehards now flock to comedy festivals — then argue about the philosophical particulars between sets. There used to be only two gatherings of note: Just for Laughs Montreal and Aspen. Two competitions: San Francisco and Seattle. Only a handful of specials and albums came out annually. Each was an industry-wide event.

Today some 40-plus comedy festivals populate the U.S. and Canada alone. Keeping track of every stand-up special? Impossible. Industry gatekeepers are far less powerful. Social media and podcasts allow comics to interact directly with potential fans. Our postpandemic stand-up explosion is now the biggest the industry has ever seen.

In the 1990s, the comedy world — and my world — was unrecognizable from today.

This reading-obsessed outlier found magazines to be a different kind of stage, one that brought the wider world to a farm in rural Missouri’s Bootheel. As Stanley Tucci’s character, Nigel, in The Devil Wears Prada, says of devouring Runway by flashlight, “This is not just a magazine. It’s a beacon of hope.” Replace Runway with Entertainment Weekly, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, and it makes sense that, as seen from the Bootheel, the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism shone like a beacon.

Principles of American Journalism. News. Library Research. And that was before they even let you into the actual J-School! From there things got serious: History of American Journalism. Reporting. Cross-Cultural Journalism. Communications Law. Also, experiential learning, such as the Mizzou Magazine Club’s annual weeklong trips to New York City, where students met with alumni, toured their fancy high-rise offices and asked them burning journalism questions.

One year, the 9/11 terrorist attacks had destroyed the World Trade Center hotel where the club previously stayed. We’d watched live coverage during Intermediate Writing class the morning of the tragedy. Afternoon ground into evening at the Heidelberg, where we commiserated and shared our shock. When we arrived the following February in New York, some of us hazarded downtown to stare at the jagged 15-acre hole. The air still smelled burnt.

It would be a couple decades before I understood how the aftermath of 9/11 would change everything I thought I’d learned about media as unbiased truth-tellers. Facilitated by the rise of the internet, it marked the beginning of major media outlets earning revenue through unbalanced echo-chambers cherry-picking news surrounding the Iraq War.

Strategic Communication. General Semantics. Magazine Design. Communications Practice. Magazine Editing, followed by Magazine Staff at Vox.

As a journalism student obsessed with culture, covering film and music seemed edifying enough until comic Dave Attell, then a national collegiate hero of his Insomniac drunk-travelogue series on Comedy Central, performed at Jesse Auditorium. He’d previously answered my novice questions via phone for a Vox preview story.

Attell’s stand-up set shook Jesse Auditorium. This was something new to me: shockingly dark but wholly unifying. We laughed so hard we gasped for air. Somewhere in me near the gut area, a new level of artistic consciousness ripped open. After the set, Attell was cajoled over to the Heidelberg. Surrounded in the dark back room by excited journalism students, he was generous with real-world wisdom — and the Jägermeister shots sent over in sugary brown waves from every corner of the bar.

Journalism had come first. Now a second focus was clear: Stand-up felt far more immediate than film or music. At the time, comedy coverage was shoehorned into newspapers’ music and calendar listings. Why wasn’t it covered in any sort of professional manner? Someone really needed to do something about that glaring journalism oversight.

I moved to New York City three weeks after graduating and covered comedy for the then robust, now-defunct New Times Media chain of alt-weekly city papers. (A 200-word blurb netted a sweet $40!) Locking in interviews required hanging out around Caroline’s on Broadway, Gotham, Stand-Up NY and the rest. The Comedy Cellar didn’t kick you out until 4 a.m. Telling rising comics that you wanted to interview them for a preview of their sets in Miami, Nashville, Houston or wherever often was met with stunned, appreciative disbelief.

There was an early Time Out New York piece on the NY Comedians Coalition, who were fighting for better pay back in 2004. For the Riverfront Times in St. Louis, a 2005 interview with Jon Stewart outlined all the big plans he had for reintroducing the world to a guy named Stephen Colbert. During a few years with Las Vegas Weekly, a young, quiet Zach Galifianakis discussed Visioneers, his trippy indie flick, years before he’d explode with The Hangover. When Don Rickles gave Attell a shout-out from the stage of Caesars Palace, Attell got so emotional he had to duck into a hallway.

Guess who ran immediately after him and stuck a microphone in his face?

Moments like these are often undercut by the realities of navigating the comedy scene. There are the times — hundreds so far, hundreds more no doubt to come — that slack-jawed door guys smirk at you in derision, wrongly assuming you’re some comic’s fangirl or evening hookup. Being a female journalist ensures you start over professionally with every story. Reputation and resumé mean less than ever.

What a weird thing to be true. Didn’t you all see my Mizzou transcript records? Would making a big speech about journalism ethics get me inside where I belong any quicker?

Alt-weeklies are long-gone in most cities. Older content is increasingly scrubbed from digital existence altogether. Between subjectivity, fictional bylines and AI, journalism itself can sometimes feel like it’s on life support, the art and craft of a well-reported story buried deep. A lot of so-called journalism doesn’t even feel like journalism anymore. It’s merely content.

What happened to the upstanding career I envisioned? The ability to make a sustainable, meaningful living? How about the truth we were taught to tell? If all the rules have been broken, what was the point of learning them?

When there’s a memorial for beloved community favorites — a Mitch Hedberg, Bob Saget or Gilbert Gottfried — watching generational titans hunched over sobbing feels like an intrusion on a sacred space. Then they get up, take their turn at the podium and make tasteless cracks about the deceased. They remind each other that’s the entire point of everything they’ve chosen to do.

In stand-up comedy, there are no rules. Just get up there and be funny. The freedom of speech is unparalleled. The hours, once talent reaches a certain level of success, are theirs to set.

The thing about a journalism degree from Mizzou is that, like any good education, the most important rules — ethics and craft — have been highly transferable. Success might sometimes feel elusive, but a Roast Battle cover story for LA Weekly became a book, Ringside at Roast Battle: The First Five Years of L.A.’s Fight Club for Comedians. My 2021 feature documentary, Too Soon: Comedy After 9/11, premiered at the famous TLC Chinese Theatre and aired on Vice TV for two months for the 20th anniversary of the World Trade Center attacks. (In Australia too!) I originated and produced Are We Good? A Marc Maron Documentary, about longtime interviewee Maron, which will be released in the spring.

All that reporting and writing involved journalistic storytelling about comedy. The final edits have just taken different forms.

Covering Mitch Hedberg inspired me to produce SiriusXM’s Hope on Top: A Mitch Hedberg Oral History. Attell, Doug Stanhope and Todd Barry have already filmed interviews for a Hedberg documentary project I’ve essentially been working on, bit by bit, for nearly 20 years. The Hollywood Reporter recently wrote about it. My recent book, A Tight 20: Two Decades of Comedy Journalism, collects stories and interviews from a host of comedic rulebreakers.

Covering the beat now as a freelancer for theLos Angeles Times offers some opportunity to spread the word about unique talent. Following the local scene and its myriad players onstage and off, exploring a million diverse opinions on religion, politics, accessibility and LGBTQ+ rights, almost makes it worth it. But the Times has less reach and fewer full-time opportunities than ever. The power and prestige of dailies and magazines have been reallocated to personality-driven, flimsily vetted podcasts.

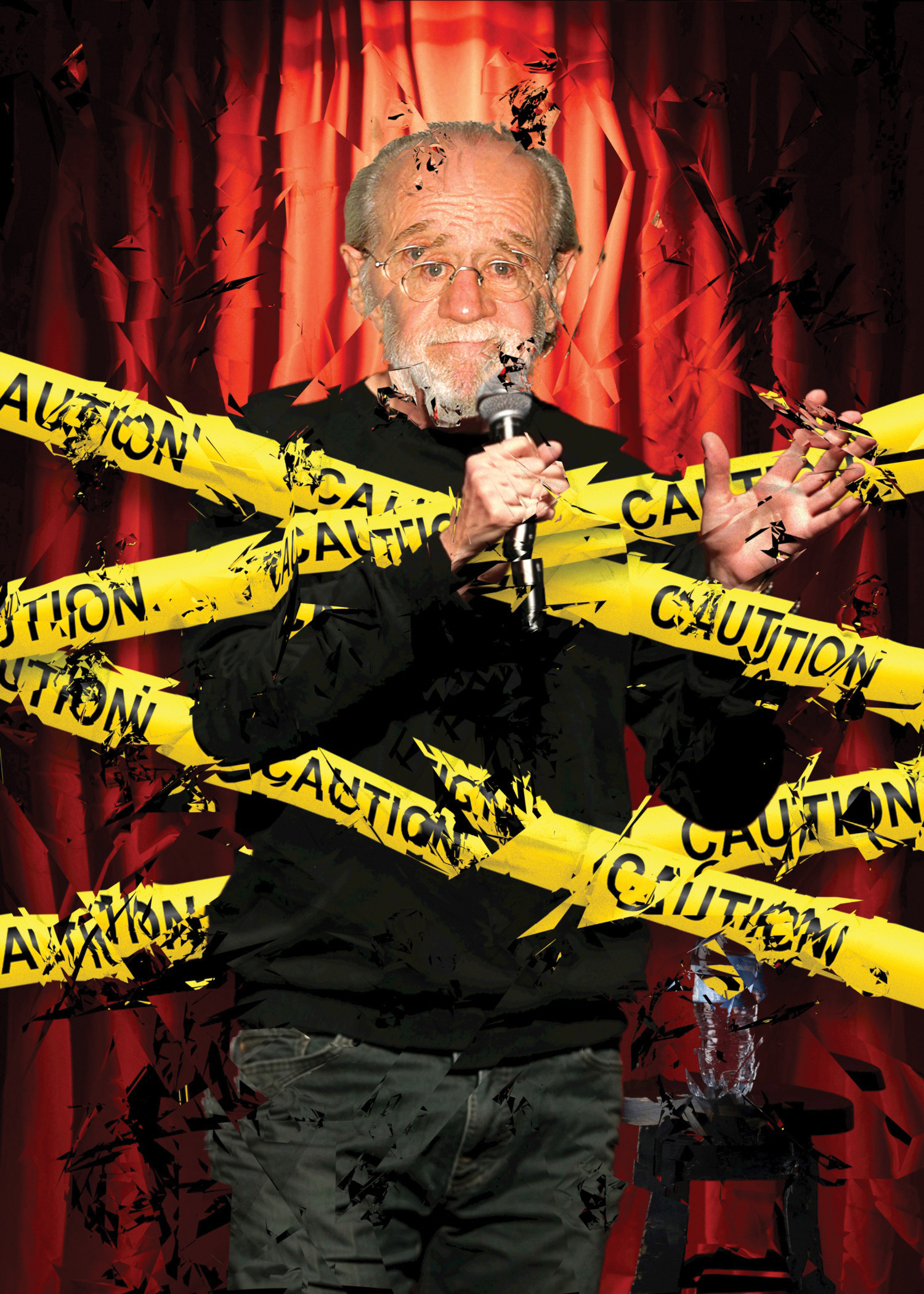

The weight of these changes lingers, shaping what it means to cover comedy and the arts today and raising questions about who gets to tell its stories. It’s a shift that George Carlin would likely have found disappointing, especially given his perspective on society’s broader trajectory. When we spoke in 2005, three years before his death, he emphasized, “Comedy comes from pain.” He believed writing was at the heart of everything, and that some people were content to entertain without really growing or challenging themselves. But others, he said, “keep changing and evolving … those people are closer to artists.”

Carlin understood: adaptation is the only real rule.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.