Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 19, 2024

Story by Dale Smith, BJ ’88

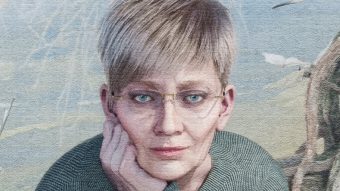

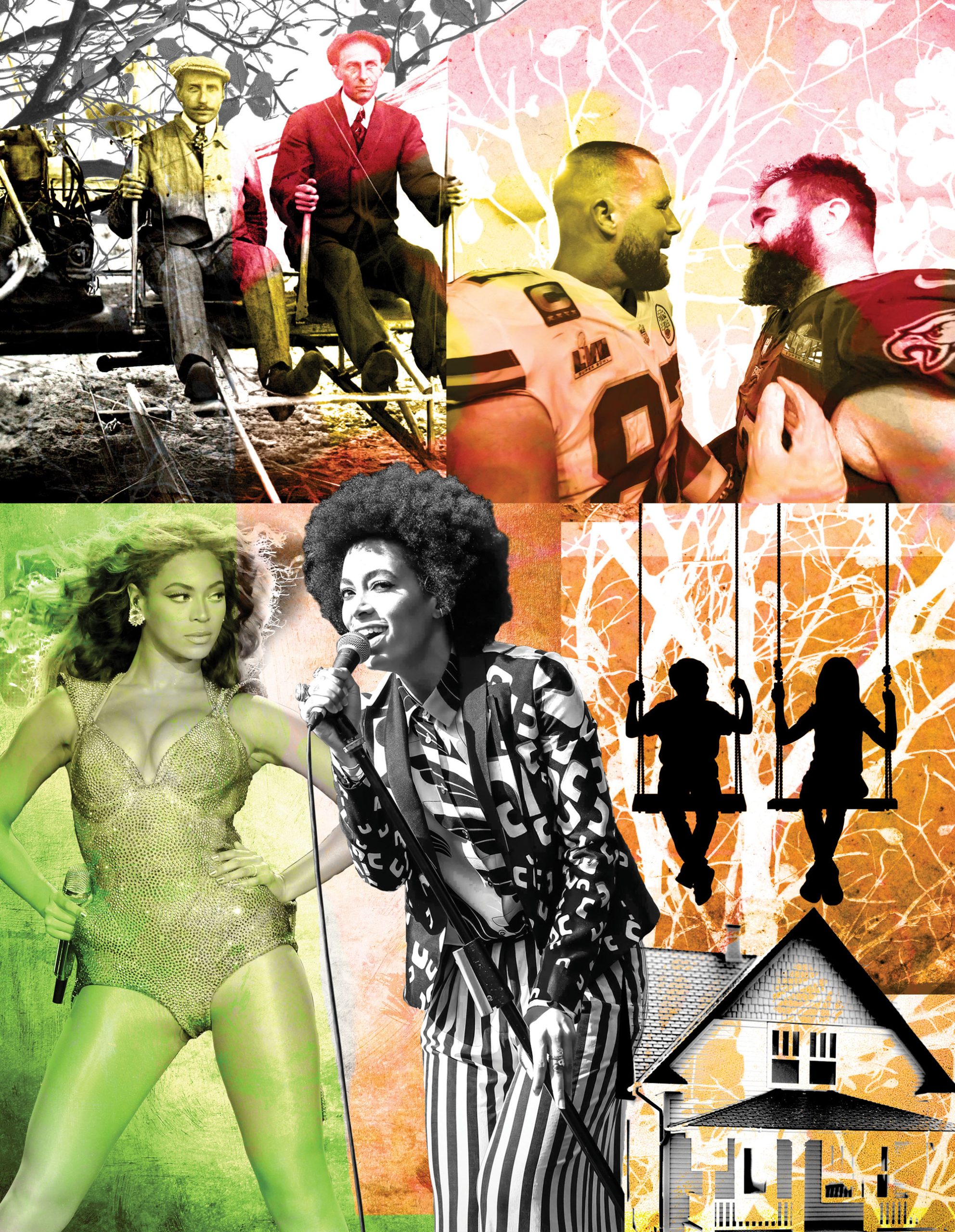

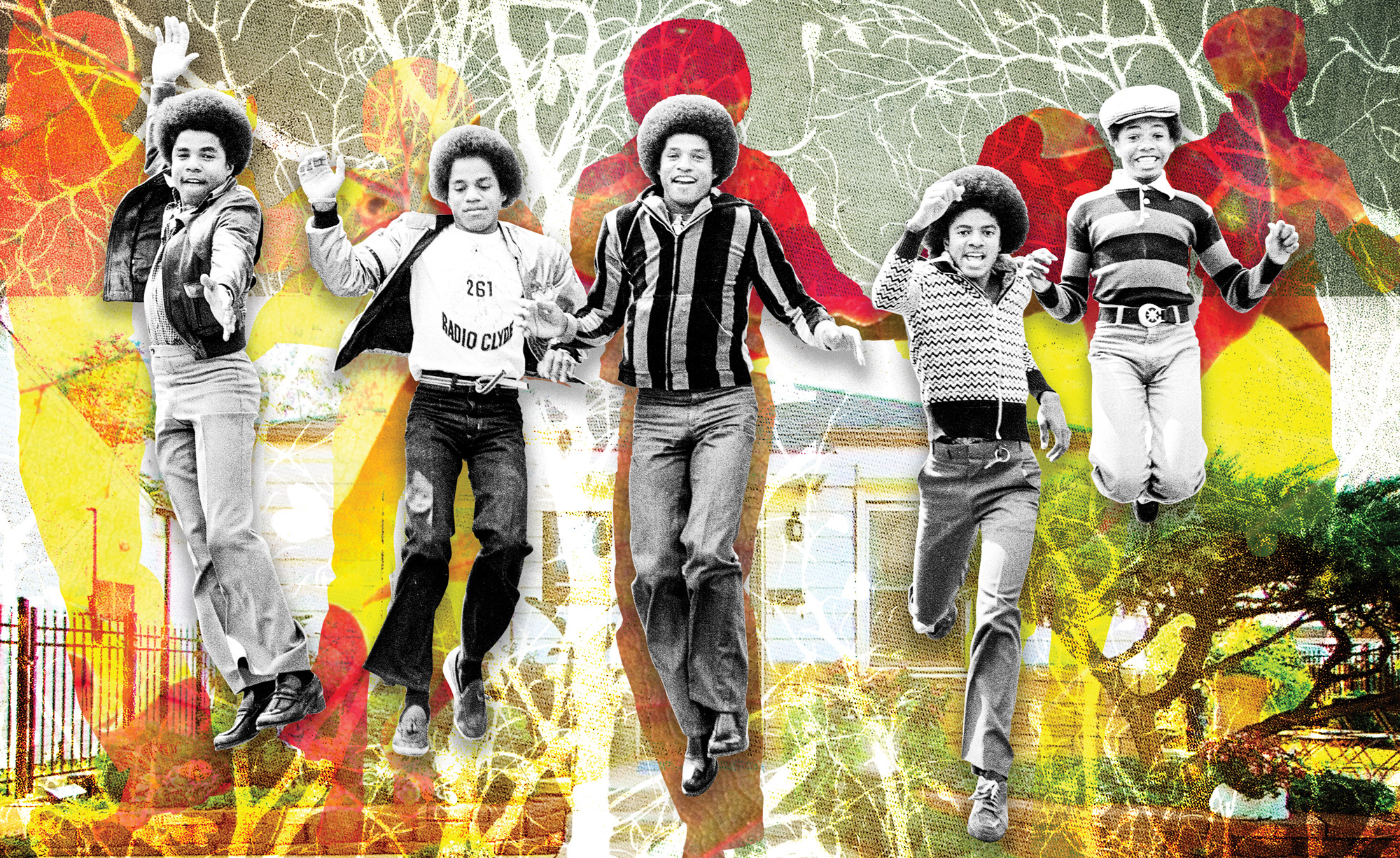

Illustrations by Blake Dinsdale, BA ’99

Brothers and sisters come into our lives long before friends, sweethearts and spouses, and they typically outlive parents. For eight in 10 Americans, siblings are their longest-lasting relationship in life. But few researchers have investigated how those bedrock bonds work, or break down, and what they mean for adjustment, health and well-being.

Mizzou has a trio of scholars publishing a wealth of studies that break ground on topics including the special roles of sisters, traits characterizing Latino families and the decades-long trajectories of sibling connections.

The researchers sort sibling relations along a continuum that might be best illustrated through relationships in various TV families, ranging from positive (warm and harmonious like The Brady Bunch) to negative (strongly conflicted, as in Succession or Arrested Development) to disengaged. Most fall between the extremes into the “love-hate” category’s alternating stints of closeness and conflict (The Simpsons, Black-ish). At 70 percent, this largest group typifies a “normal” childhood and adolescence.

Adolescent angst

Curious about the causes and consequences of sibling conflict, Nicole Campione-Barr, professor of psychology, decided to investigate. When she asked hundreds of young people in grades six through 12 why they argued with their brothers and sisters, a pair of conflict zones emerged: equality and invasion.

“The equality issue is about sharing space and resources with someone you live with — things like sharing the video game system or who does which chores or who gets to sit in the front seat,” Campione-Barr says. “Then there’s the impingement of one’s personal domain — failing to ask before borrowing things or coming into a sibling’s room, hanging around when they have friends over. It’s trampling over their autonomy and sense of self.”

Even though conflict between adolescents is generally more frequent than intense, Campione-Barr says, quarrels in both zones had downsides. Equality conflicts slightly increased depressive symptoms during the one-year study, perhaps when a child felt parents dealt them lesser treatment than siblings. More serious are the invasion-of-personal-domain conflicts, which in the study diminished the quality of sibling relationships.

“Invasion issues led to decreases in trust and communication, as well as higher levels of anxiety,” she says “If you are constantly feeling this sort of threat, you are always alert and on edge.” Typically, harsh feelings are temporary, with ensuing moments of brotherly and sisterly love. But could the emotional whipsaw damage sibling cohesion over time? Campione-Barr and Sarah Killoren, associate professor human development and family science, co-wrote a research review article tallying the ups and downs.

“One of the biggest parenting concerns has always been, ‘My kids just won’t stop fighting. I don’t know how to fix this,’” Campione-Barr says. She and Killoren found some comforting observations in the scientific literature. First, kids safely can learn how to disagree and debate effectively with brothers and sisters because they have roughly the same amount of power (unlike parents and bosses), and they aren’t going anywhere (unlike peers and romantic partners). Second, the amount of conflict matters far less than the presence of warmth and support. Third, as siblings grow into adulthood, the negativity tends to dissipate, and the warmth remains.

(For research-based parenting advice, see “Adolescent Siblings: A Parenting Guide” below.)

Talent, skill and sibling power have run in the family for the Jackson 5.

Bigger emotions

Sisters played an outsized role across studies, with the sister-sister bond excelling in multiple dimensions. In adolescence, sisters have the most emotionally intense relationships, Killoren says. “By middle adolescence, the conflict part diminishes significantly, and primarily the positive is left by late adolescence and young adulthood,” Campione-Barr adds.

That intensity can grow as sisters discuss personal matters. To find out how, Killoren asked pairs of sisters to talk about dating and then analyzed the conversations. Sister-sister bonds are “similar to friendships but nonvoluntary because of shared family ties,” she says. “You can have real ‘I hate your boyfriend’ chats with siblings that may end friendships.”

In these conversations, sisters shared dating stories with each other and often agreed on conclusions, but the older, more experienced ones took on the extra role of giving advice. Killoren observed that while younger sisters usually try to stand out by being different from their older siblings, here they wanted to avoid their sibling’s dating mistakes.

Although researchers generally find the sharing positive, the intimacy can come at a cost. It can go wrong when a brother reveals troubling information to a younger sister — body-image concerns or risky behavior such as smoking or reckless driving, Campione-Barr says. “They want to be there for their brothers, but they don’t know what to do with that kind of information. It’s more for parents to deal with,” she says. In the end, the brothers feel better having confided the problems, but the younger sisters feel worse.

Family front and center

Killoren’s research focuses on the important role sibling relationships play in the development and emotional well-being of Latino youth. Her studies explore how siblings influence each other’s behavior, values and coping mechanisms, particularly in navigating family dynamics and cultural pressures. Her many studies of Latino families have uncovered clear differences from the white, middle-class subjects of most sibling research. They had the most siblings in the love-hate group (70 percent) and none in the uninvolved category. This may stem from how Latino families place a higher value on familism — seeking help and advice inside the family — than other demographics, Killoren says. “Eighty-five percent of Latino siblings had moderate to high intimacy, which is higher than other groups.” The positive relationships led not only to fewer depressive symptoms and risky behaviors but also to more caring for others, taking responsibility and concern for social justice.

When adolescent girls in these families begin dating, family remains front and center, with older sisters getting to know dating partners. Many older brothers react in two phases, first intimidating dating partners and later developing relationships with them. Killoren says the brothers’ protective behavior is an aspect of caballerismo, a Latino ideal of honor and chivalry.

Most sibling researchers have investigated childhood and adolescence, but how do the relationships endure through the decades? Megan Gilligan, associate professor, is publishing some of the first findings from studies that piece together trajectories of sibling ties from teenage years well into middle age.

Coming out of adolescence, age 23 is a turning point, “a time when both conflict and warmth are kind of muted,” Gilligan says. Siblings are less likely to live together as they make transitions to college, careers and romantic relationships. “It’s not that siblings no longer matter, but their salience decreases.”

Even so, the “I love my sister, but she drives me crazy” dynamic of adolescence remains part of the picture over time, she says. Old wounds from rivalries, feelings of favoritism and the like are associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms into old age.

The case of favoritism is surprising. “When we ask older mothers, they typically specify a ‘favorite’ child. When we ask the children, they say, ‘Yes, she has a favorite,’ and offer a name, but they rarely match,” Gilligan says. Perceptions of fathers’ favoritism are more strongly associated with sibling conflict, perhaps because fathers’ expressions of affection generally are a scarcer resource. “We carry these often-incorrect beliefs for decades,” she adds. “It’s not the kind of thing that most families talk about at the dinner table.”

(For research-based advice on maintaining long-term relations with siblings, see the sidebar, “Adult Siblings: A User’s Guide” below.)

Solidarity or stress?

The death of a parent can either bring children closer to one another or drive a wedge, Gilligan says. She has observed siblings with strong relationships coming together when parents need care at the end of life. More often, though, she sees brothers overestimating their contribution to such care, the bulk of which sisters deliver. The sisters grow closer to each other and resentful of the brothers as traditional gender roles play out.

“Women tend to be socialized to be more invested in family relationships,” Gilligan says, “to have closer ties with mothers and sisters, as well as more conflict. So they are used to navigating complex relationships.” Men generally are less practiced in dealing with mixed feelings and so may avoid such situations.

“We hope the death of a parent is a moment of clarity and solidarity, and it can be,” Gilligan says. “But families tend to hold on to early patterns of interaction. For those with long-term tensions now dealing with stresses of caregiving, the crisis amplifies it.”

As brothers and sisters turn 60 and beyond, Gilligan says, some conflict may remain over the same old issues, but many older adults report having warm relations with brothers and sisters. As older people leave their careers and deal with problems such as illness or the loss of a spouse, their siblings can be lifelines.

“At this stage of life, siblings can regain their salience,” Gilligan says. “People may be having less contact with their own children, and sibs can fill some of that gap. These ties still matter.”

Adolescent siblings: a parenting guide

• Parents can minimize equality tussles by dividing responsibilities evenly and creating family rules and chore lists that prevent daily accusations of unfairness. If one child needs special treatment, such as additional parental help with homework, be clear with siblings about the reasons. “When they understand why, it doesn’t harm relationships. But, if not, it can lead to feelings of ‘They love me less,’” Campione-Barr says.

• When it comes to personal domains, families with adolescents need to respect boundaries, Campione-Barr adds. “Siblings need to knock before entering. Parents should have conversations first before sitting down together to look through phones.”

• Although learning to navigate sibling conflict is a valuable developmental stage, how much is too much? Gilligan advises parents to help their children find a sweet spot where conflict can play out as they deal with challenging situations. “But be aware if it becomes too intense, such as yelling and screaming or physical violence. Ask kids about how much tension they are feeling around this.”

• Another key to helping children build lifelong bonds, says Campione-Barr: Create situations where they can engage in positive experiences – the stuff of family storytelling. “Maybe they fall in love with the same sport or enjoy family trips where everyone gets to do something they like. Those warm feelings endure.”

Adult siblings: a users guide

By the time brothers and sisters are grown-ups, they’ve got a history that likely includes not only fond memories but also some regrettable behavior toward one another. “Those negative experiences can be hard to let go, and we carry them with us into adulthood,” Gilligan says. “People who acknowledge that history can be in each other’s lives throughout the life course.”

Gilligan counsels conversation in the following areas as well.

Favoritism: Siblings who bring up the “Mom or Dad always liked you best” conversation might uncover some surprising truths that can ease old tensions. It turns out those assumptions about being the favorite are often wrong.

Care of parents: Parents almost certainly will need help during illness and old age, but families often react to these highly charged situations as novel crises, Gilligan notes. She suggests siblings discuss together and with parents how they’d like to handle challenging times. “These can be hard conversations to start, but we should have them and try to normalize responses.”

Irreplaceable roles: Mothers typically take charge of maintaining family relationships by, for instance, planning holiday gatherings. They also keep the peace when emotions run high. When a mother dies, Gilligan counsels against the urge to make new traditions. Instead, the younger generation can help keep the family together by acknowledging what works for them. “Maybe they agree to collaborate on a big Thanksgiving dinner every year. That would be a way to maintain a family legacy.”

Reconnect: New research is clear about the benefits of sibling relationships in later life. They decrease feelings of loneliness. So, Gilligan says, pick up the phone, get together and tell the old family tales.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.