April 6, 2023

Contact: Courtney Perrett, 573-882-6217, cperrett@missouri.edu

Photos by Abbie Lankitus

Nestled deep in the Heartland is a world-class research center where scientists at the University of Missouri have been working for more than two decades on genetically modifying pigs to prevent diseases that threaten both swine and humans. Under the tutelage of Randall Prather, a Curators’ Distinguished Professor and director of the National Swine Resource and Research Center (NSRRC) at MU, researchers have pioneered technology using pigs that has provided the foundation for successful transplants in humans, including the first-ever partial heart transplant in a six-month-old baby by a team of Maryland-based surgeons in 2022.

Genetically modified pigs are now used to study a range of human ailments, including cystic fibrosis, retinitis pigmentosa and cancer. Many other technologies have been developed as well, such as those to create a heart and kidney that resist hyperacute rejection when transplanted.

Prather and his team’s longtime work has made the NSRRC the go-to source for genetically modified pigs used nationwide to push forward discoveries. In the coming months, the NSRRC will double its capacity with a goal of broadening swine genetics lines.

Investments in innovation

The NSRRC, which serves as a core National Institute of Health center for researchers across numerous fields, is expanding with the support of an NIH-funded $8 million grant with just over $30,000 in university funding.

“The expansion of the NSRRC will enhance our ability to meet the needs of the NIH community by providing space to house critically needed models of human disease,” Prather said.

Additionally, South Farm Swine Research and Education Facility Addition, a recently completed building, will add another 12,000 square feet to the existing facility to accommodate housing for the animal models used by faculty who are studying genetic engineering in large animals. The project is funded by a $5 million grant from the NIH Health Resources and Services Administration with an intended completion date of 2025.

A legacy of success

Prather underscored the need for more research space on MU’s campus to be able to continue cutting-edge research. Because pigs are physiologically similar to humans, research centers like these at MU are fertile ground for scientific discovery that doctors can use to address real human ailments like cancer and cystic fibrosis.

One of the most notable legacies of the Prather Lab is the partial heart transplant done by Duke Health surgeons in early 2022. Essentially, doctors tested whether heart values could be transplanted into pigs with the surrounding tissue, allowing the valves to grow. Success in tests on swine models later enabled doctors to do a partial heart transplant in a six-month-old baby born with a congenital heart defect, saving the child from countless high-risk surgeries that would’ve been inevitable without such technology.

The Prather Lab’s research has spanned decades and seen many advances both biomedically and through improvements in patients’ well-being.

One of scientists’ first breakthroughs in the early 2000s was creating what they termed “knockout pigs” – described for the portion of DNA that was deleted in their genetic codes. Using gene editing technology, Prather deleted a molecule on the surface of these pigs’ cells (specifically white blood cells in the alveoli of the lungs) to ensure the animals weren’t infected by diseases such as porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), a prolific disease that costs the pork industry millions of dollars every day.

This innovation primed medical researchers for successful xenotransplantation going forward (the process of moving an organ from one species to another).

Looking to the future

Although there is still a long way to go before pig-to-human transplants might become mainstream, Prather and his team are confident in the foundation they’ve built.

“The investment in these facilities will enable the medical community to have expanded access to animals to develop and test urgently needed treatments and therapies,” Prather said.

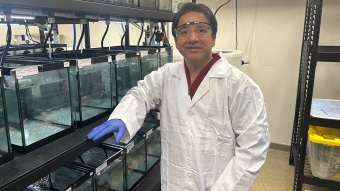

Wells grew up in the Great Smoky Mountains in east Tennessee and attended North Carolina State University in Raleigh, where he studied genetics. From the beginning, he expressed an interest in understanding how diseases function in animals — particularly pigs — and how genetic engineering could help improve things like digestion. After receiving his doctorate, Wells went on to work for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), where he worked in the lab that created the first genetically engineered pigs, sheep and rabbits.

“My passion is agriculture. I want to do everything that I can do for my talent set to be used to cure diseases,” he said, explaining that while most funding is geared toward biomedical research, these innovations are applicable to agriculture, too. “I'm glad that we can lend swine technologies to the biomedical world and that the pig fits into both categories. The technologies of one can be leveraged to improve the other in both directions. Those are good things.”

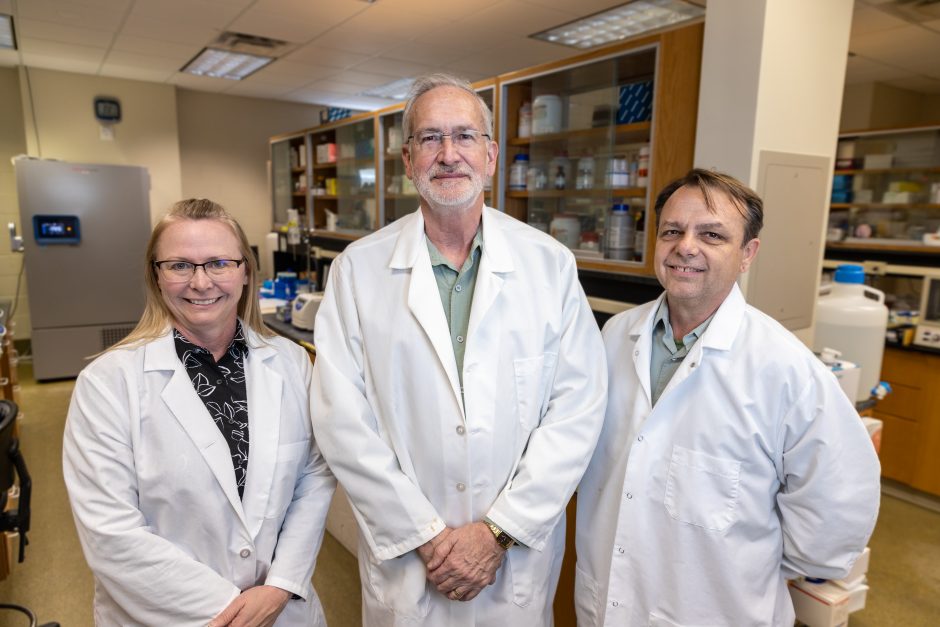

Kristin Whitworth is the associate director of the NSRRC, where she oversees the coordination of the center’s different projects and initiatives. Primarily, Whitworth serves as the point-person between medical specialists who request models and the genetic engineers who work to supply them. When she isn’t at the center, Whitworth is immersed in her specialty research interest — exploring how disease resistant models function and how this knowledge translates to instituting cures for human-born illnesses.

After getting her undergraduate degree from Illinois State University, Whitworth planned to go back to school to study reproductive biology. Then, Prather’s program was gaining notoriety in animal sciences spaces, inspiring her to work in his lab, where she’s been ever since.

“My favorite part of my job is when there’s a success story, in other words, when there’s a result that benefits either people or pigs,” Whitworth said. “It was exciting when we made pigs resistant to the PRRS virus, so if that gets incorporated into swine herds, we would prevent pigs from getting these diseases. It’s exciting to know we’d made a huge impact there.”

Whitworth also cited the partial heart transplant performed by Duke Health surgeons in early 2022 as a foremost success story, even if the NSRRC’s contributions were indirect.

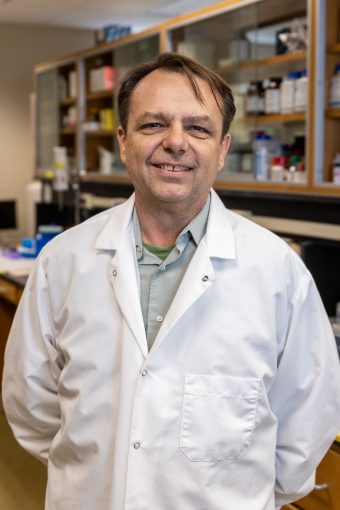

Melissa Samuel is the manager of research activities in the NRSSC. After starting a biology degree at Truman State University, she visited a friend at Mizzou and sat in on an animal science lecture that quickly triggered her interest in studying the relationship between animals and genetics. Three years later, she graduated from MU with a degree in animal sciences. During her time in college, Samuel had a summer job at the MU Swine Farm, where she worked in the farrowing house and cared for the pigs.

“I learned that Dr. Prather was researching swine and reproductive biology and DNA, so I found a part-time job in the lab and told him that I really would like to work in the lab after graduation,” Samuel said.

Then, the NSRRC was a few years away from being built. Now, Samuel has worked in Prather’s lab for almost 23 years. In the lab, she coordinates supplying swine models to researchers and institutions for biomedical innovation. Samuel spends a good part of her time in the swine center caring for newborn piglets, a job she says is integral to the success of the lab and its greater agricultural and biomedical goals.

“The Prather lab is a great lab,” Samuel said. “There are quite a few members that have worked together for at least 15 years — I think that says a lot about our workplace. I also like what we’re doing as a lab, which is improving the health or way of life of people with certain diseases that there may be no cure for yet.”