Published on Show Me Mizzou April 27, 2023

Story by Dale Smith, BJ ’88

Leslie Lyons arrived at her new home in Columbia a decade ago to the happiest of coincidences.

“Lo and behold,” she says, “there were a cat and her litter of kittens living under my porch.” Both a cat lover and the world’s leading feline geneticist, she developed relationships, some closer than others, with the mother and her offspring — connections that illustrate a key element of her latest study looking at the origins of cats around the world.

Published in November, Lyons’ research lays critical groundwork for improvements in the health of cats and, therefore, humans, as the species share numerous diseases and genetic characteristics. “Everything you need to learn about human genetics you can learn from cats,” she says.

Her life revolves around cats, whether through her comparative medicine research in the College of Veterinary Medicine or her home life, which includes former under-porch dwellers Prince Harryhausen, Meow Meow Kitty and BratCat.

And then there are her trips to cat shows. “She is highly revered in the cat-fancy community,” says Jonathan Losos, a geneticist at Washington University in St. Louis and fellow lover of felines. He touts her extensive research, as, among other things, the basis of popular cat DNA tests. Based on a mouth swab, such tests can inform adoring owners about their cat’s breed and reassure them about blood type, predisposition to diseases and more.

Lyons has admired feline beauty and athleticism since her days as a three-sport high school athlete, but her academic career began in the genetics of human beings. Finding that field less than collegial, she considered research positions dealing with fish, cows and, fatefully, Felis catus. With all she has come to know as a scholar and loving owner, her estimation of cats has risen. She extols them as “moving artwork” and “God’s perfect little specimens.”

Writing an origin story

Part of that perfection, she says, lies in how cats synchronized their evolution with that of humans some 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent. The area was a more lush and pleasant place then, she says of the bountiful lands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now Iraq and Syria. It is where people began remaining in place year-round, growing sorghum and wheat. With that came grain stores and refuse piles that not only attracted mice but also made them prolific. And problematic. Mice dined on grains the people had worked so hard to grow and store for leaner times.

Then as now, the Fertile Crescent was also home to a species of wild cat looking much like today’s household tabby, only larger. Their hunger for the rodents put them in proximity to the ancient farmers. The cats saw the food and realized that, to get to it, they had to venture near humans. “They thought to themselves: ‘Either I have to raid into the village to hunt mice and get back out. Or, if I’m friendly, maybe humans will take me in and help protect my babies,’” Lyons says.

But living among humans? Becoming allies? That’s a big reach for a wild animal.

She thinks that people, seeing how effectively cats hunted, offered the mousers extra encouragement to stick around, perhaps with gifts of milk and meat. Lyons did the same with her family of strays. “A couple of kittens would eat the food I left them. Some would let me touch them and eventually realized they weren’t harmed. But the mother never let that happen during the seven years she was around the house. One of the siblings still doesn’t let me touch her. But Prince Harryhausen won’t get out of bed with me.”

The difference between these family members is codified in their DNA. All those millennia ago in the Fertile Crescent, she says, “A mutation enabled a group of cats to be bold and come in and be tolerant of humans. They domesticated themselves. The ones with the mutation who lived near humans got help procuring food and were able to propagate better.” Archaeological evidence

supports this survival-of-the-friendliest scenario.

Scientists know that, for cattle, instances of domestication played out independently in different parts of the world, and now we have both Angus and Indian cattle species from different progenitors. It’s a similar plot for rabbits and other species. But for cats, the origin story has remained unanswered, Losos says. Researchers had created competing theories of whether cats domesticated once or multiple times in various places.

Lyons set out to answer that question in her latest study, which appeared in the journal Heredity. If cats could domesticate in one early agricultural setting, Losos adds, then why not elsewhere, such as China and Southeast Asia? There were plenty of mice to go around.

Losos says that Lyons’ study would “put the final nail” in one of the theories.

Gathering DNA

To figure it all out, Lyons gathered genetic samples of almost 2,000 random-breds — think feral, alley, house, community, street or barn cats. Then, like the forensics experts on the TV series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, she built and analyzed a 138-marker DNA profile on each cat to learn how much they shared with one another and how much was unique.

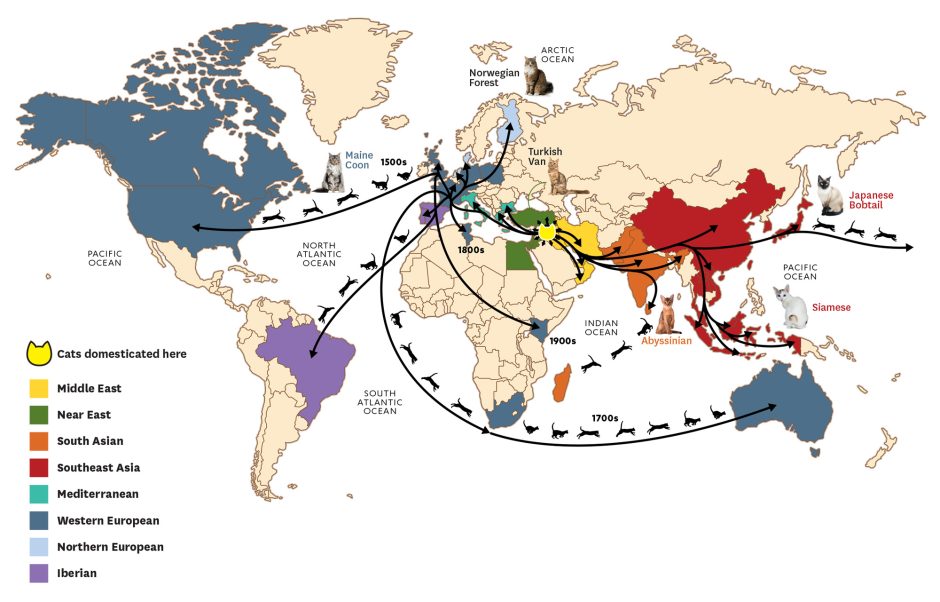

Some markers track genes that mutate quickly to tell the story of changes over the past few centuries. Other markers mutate slowly and reveal a cat’s lineage going back millennia to their wild progenitors. Because samples came from 40 countries covering the planet’s distant reaches, Lyons could discover how far afield descendants of those early domesticated cats migrated from the Fertile Crescent, if at all.

And wander they did. First stop, Egypt. By about 600 B.C., Egyptian priests had exploited the popularity of Bastet, the warrior goddess of feline fertility, by becoming the first for-profit cat breeders, Lyons says. They sold mummified cats as a sort of votive offering. Inexpensive versions came wrapped in fabric. Pricey mummies could be housed in carefully painted caskets.

“Buying one was like lighting a candle in church. You chose the big one or the little one,” Lyons says. They were made by the millions, she adds — so many that sailors used them as ballast.

During the first 1,500 years of the current epoch, cats likely traveled with traders along the Silk Road from East Asia to Europe. From there, they traveled along with European explorers, traders and colonizers. Perhaps due to the British Empire’s dominance after 1600, felines in Kenya, to this day, carry more European feline genetic material than other cats in the region.

The farther cats roamed from the Fertile Crescent, the more they evolved away from their ancestors through typical random mutation, Lyons says. In India, cats shed the tabby pattern. Long-haired angoras popped up in the Near East. On the Isle of Man, the tail disappeared.

Stalking the mousers

Clearly, cats in various places around the world are genetically distinct, and Lyons set out to map those differences for two big reasons. First, she needs good data to build genetic tools that improve cat health.

Second, the study contributes to her broader goal of using cats as a biomedical model to improve human health. Both species suffer from polycystic kidney disease, for instance. When in 2004 she and others launched a genetic test for the disease, 38% of Persian cats had it. “Now the number has gone down considerably thanks to our efforts,” she says. That success could pave the way to medical advances for humans.

Even though cats have developed some genetic diversity since their domestication, it’s just a few thousand genes out of billions. “That’s nothing,” Lyons says. They’ve continued to hunt vermin in their symbiotic relationship with humans, and, like Prince Harryhausen and the rest of her porch family, they can still live and breed in the wild. Perhaps it would be better to call them semidomesticated.

Only during the past two centuries have people bred cats for their looks as a sort of fashion statement. “People want to think their cat is some special breed,” Lyons says. But her planet-wide data turned up just one progenitor. And so your cat — whether behaviorally friendly or aloof, whether visually common or exotic — descends from the friendly mousers of the Fertile Crescent 10,000 years ago, she says. “It’s really ancient.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.