Published on Show Me Mizzou Sept. 4, 2023

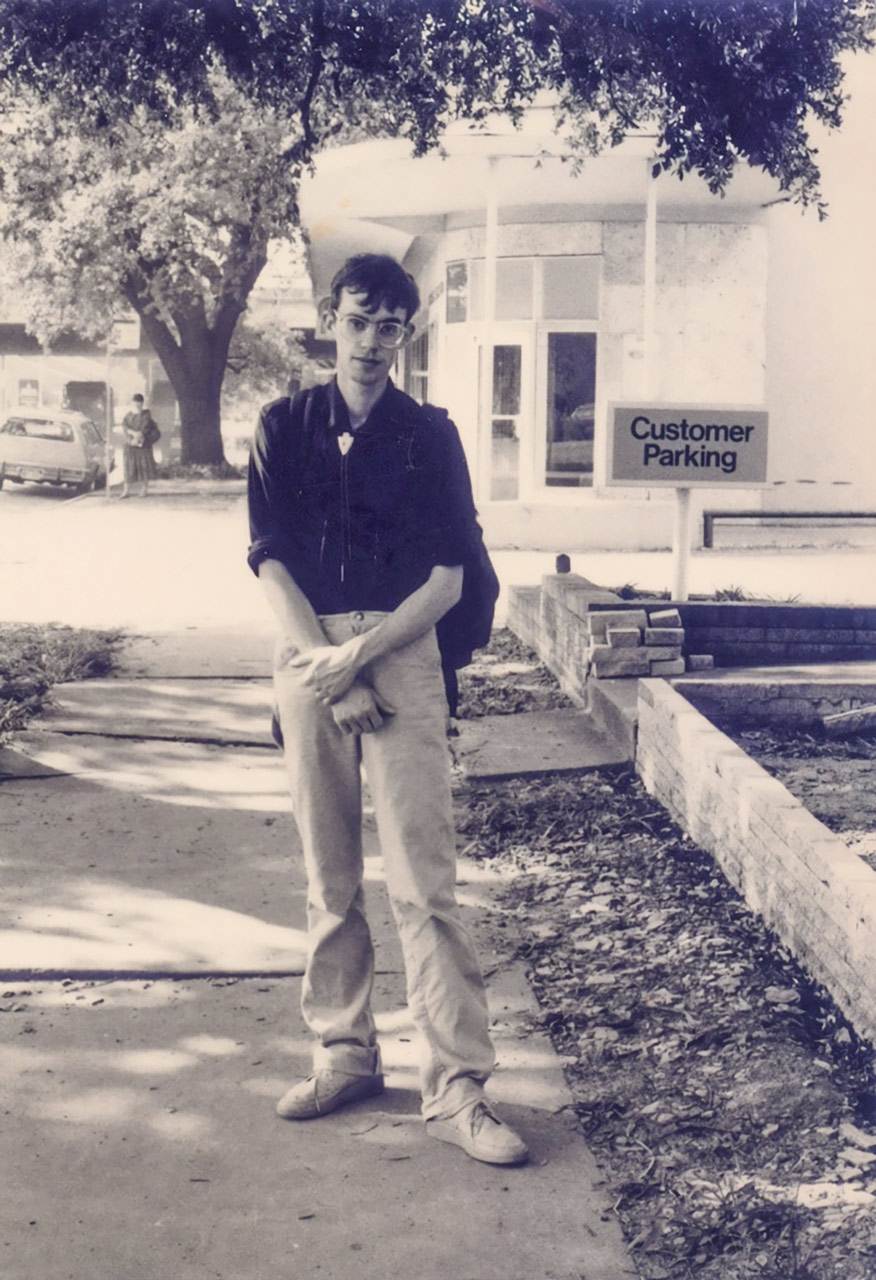

Story by Chuck Eddy, BJ ’82

When Chris DuPre showed up at recently opened music venue the Blue Note one afternoon in May 1981 to interview singer-songwriter Jonathan Richman for the Missourian, the 30-year-old bard of leprechauns and little dinosaurs was practicing cartwheels in front of the stage. DuPre, BJ ’82, wondered, “Is this childish thing a put-on?”

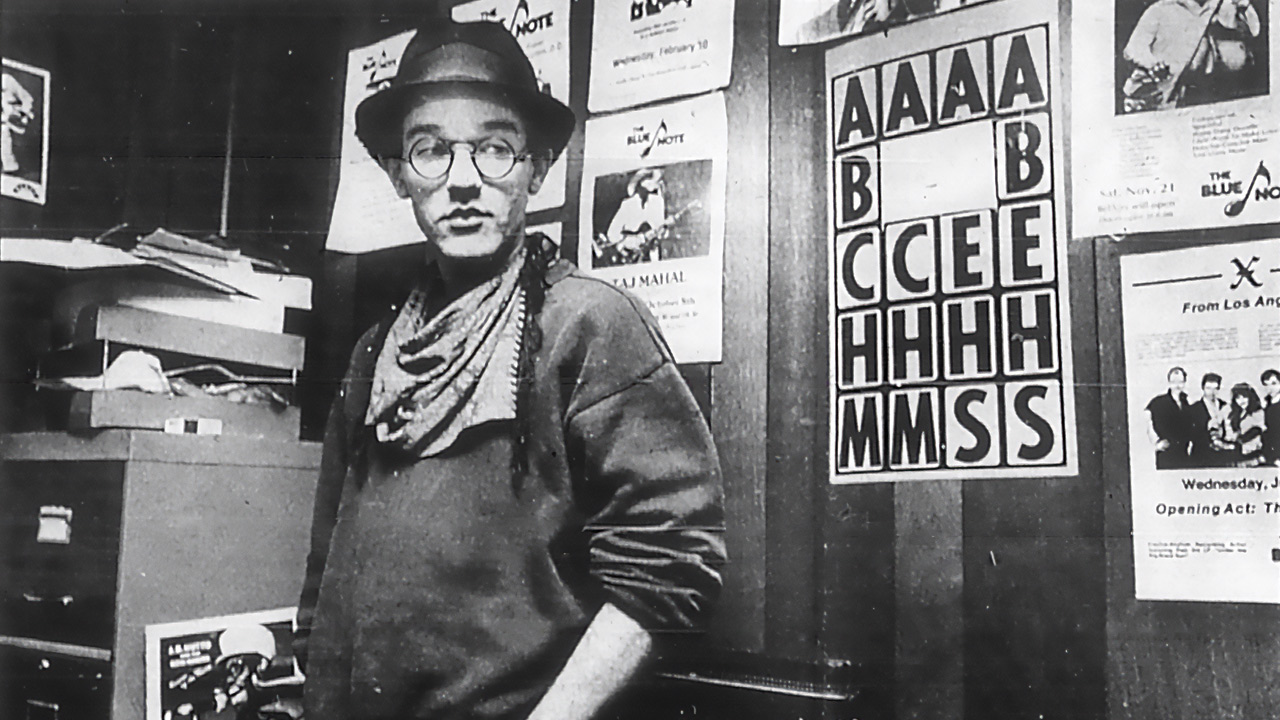

Richman, best known in pop culture for his musical commentary in There’s Something About Mary, assured him it was not. That same day Richard King, co-owner of the new club, drove Richman to KCOU, the campus radio station run entirely by University of Missouri students.

“We were always promoting shows,” Trish Merelo, BA ’84, KCOU’s music director at the time, recalled to me this spring. “We worked hand in glove.” So she interviewed Richman over the air.

The previous summer, on a record-hot August day, the Blue Note had taken over gritty 500-capacity biker hangout Brief Encounter on Business Loop 70 at the north end of Eighth Street — 2 miles north of KCOU’s broadcasting studio, then in Pershing Hall. The music scene in early ’80s Columbia — which, as a Mizzou journalism student writing about music for the Maneater and Missourian, I operated somewhat on the periphery of — amounted to an ecosystem.

DuPre, for instance, also worked the counter at on-campus used-vinyl store Whizz Records. The shop, recalls former employee and KCOU program director Brian Long, BA ’86, was “just a little ramshackle” shanty founded by an Armenian ex-pat who’d previously helped start a commune while studying geology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Part of a Jesse Hall-adjacent strip of storefronts on Conley, including storied initials-carved-in-booths dive the Shack, Whizz drew an intriguing clientele of students and outcasts. I spent so much time there myself that at least two people I talked to for this article assumed I had worked there.

Truth is, when I arrived in Columbia on a full-tuition Army ROTC scholarship in 1979, I didn’t own many records. But that didn’t stop me from diving right in at the Maneater — first with the two-years-late U.S. edition of the Clash’s first album. Before long, I was reviewing funk, country, even jazz as well as new wave (including four consecutive Elvis Costello) albums and critiquing concerts I had no business weighing in on — B.B. King and Dizzy Gillespie, not to mention a 1980 REO Speedwagon date at Hearnes Center that I hilariously dismissed as “Midwestern, metallic and cruddy,” thus inspiring an abundance of deservedly angered response.

I was also a regular customer at Streetside Records, Columbia’s biggest vinyl retailer, a few blocks northwest of campus. The store provided KCOU with a monthly stack of free LPs, recalls news-guy-turned-DJ-turned-general-manager Jeff Propst, aka George Blowfish, BA ’81. “Blue Notes,” a weekly Maneater advertorial, hyped imminent gigs, KCOU shows and Streetside product. Everything was interconnected.

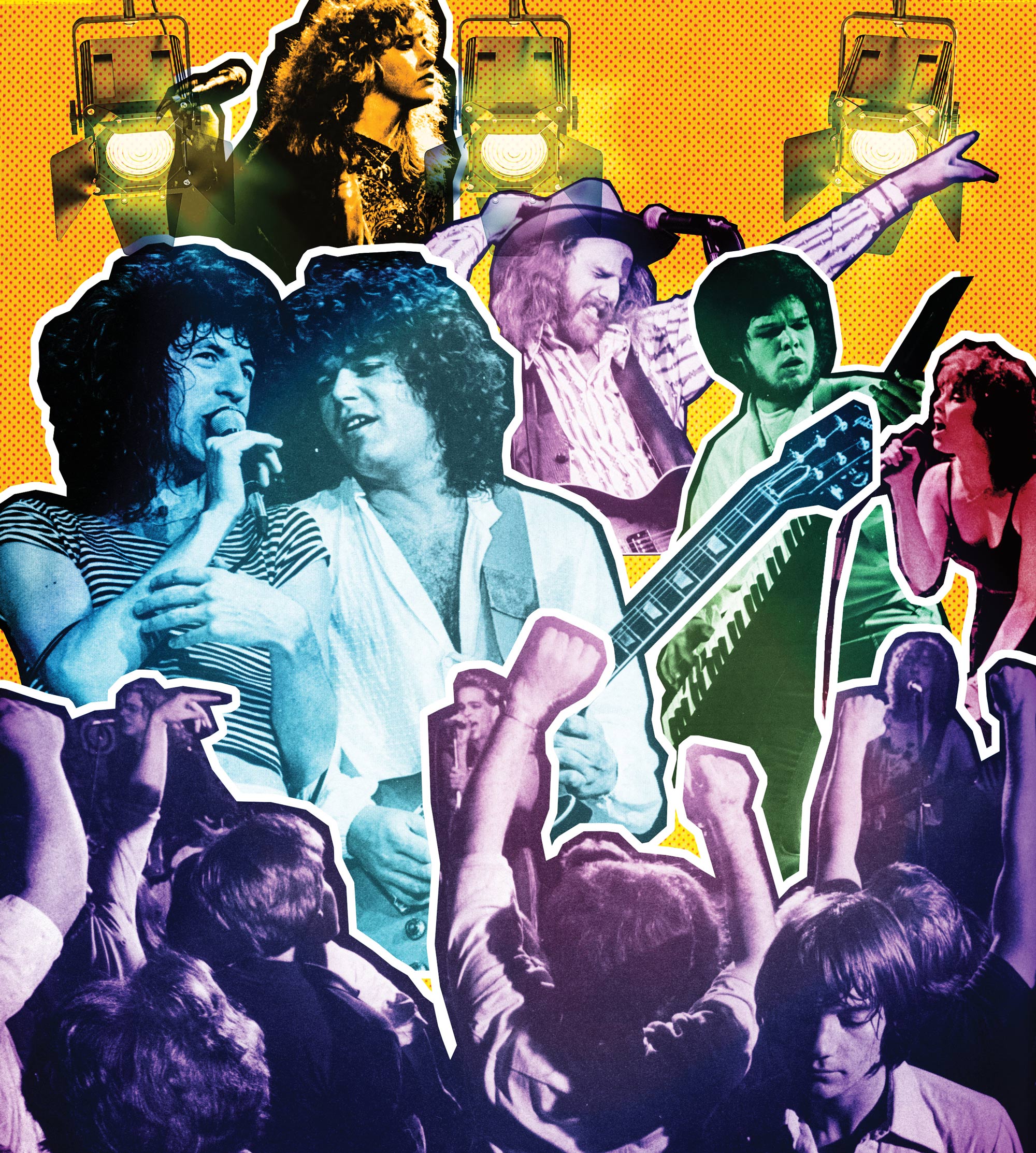

Clubland

These connections ran deep. The Blue Note’s origin story qualifies as local legend: Richard King coming into town to visit his friend Kevin Walsh, A&S ’77, in October 1975; Walsh getting King, then King getting Phil Costello, jobs at the Heidelberg; Costello and King reinventing Brief Encounter as the Blue Note, after which King stayed on as owner until selling it in 2015. Walsh, for his part, wound up managing Streetside for a good quarter century. Plenty of people worked at both, and plenty used both — not to mention KCOU — as stepping stones to the greater music industry.

The Blue Note’s next-door neighbor was the Pow Wow Lounge: “A rough, rough bar,” Costello says, whose rowdiness “would spill over.” To discourage boozed-up bikers, the Blue Note would triple their cover charge.

What was the best concert you saw at Mizzou? Tell us about it here.

On Wednesday nights, when two bucks could get you a Long Island iced tea or a pitcher of Old Style, Costello would spin the Smiths, early hip-hop and “cool dubby Clash stuff” starting at 8 p.m., eventually closing with UB40’s “Red Red Wine” at 1 in the morning. The event was called, simply, “Dance Party.” “After three months,” King boasts, “we were packed.”

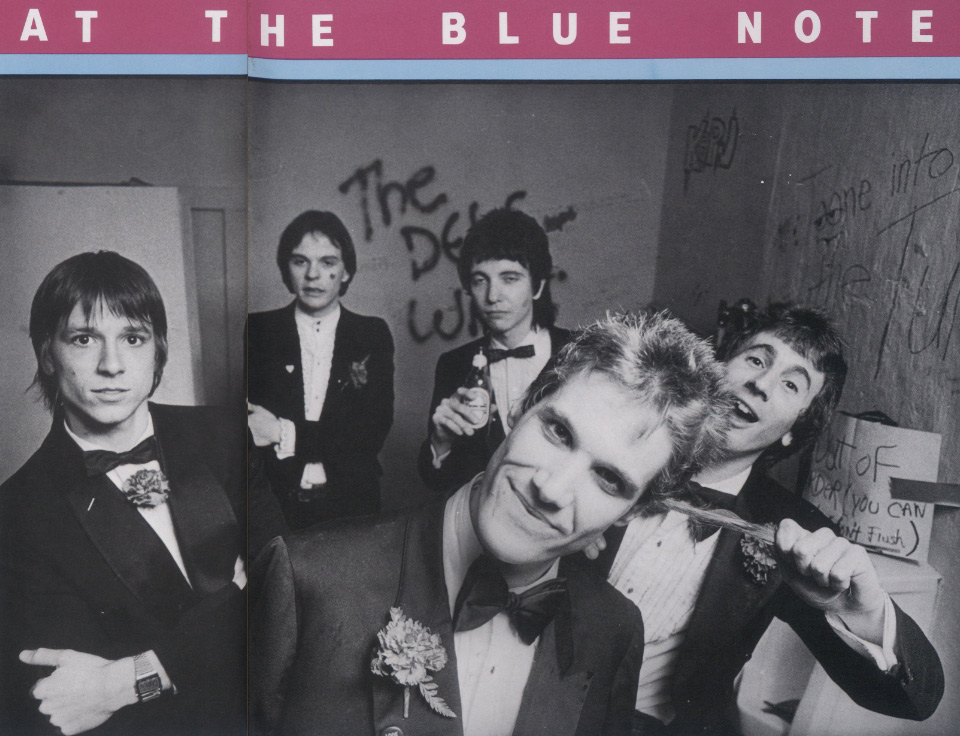

The Blue Note started booking up-and-coming indie rock and post-punk bands early on; the Embarrassment, Get Smart!, Pylon and Elvis Brothers from fellow college towns like Lawrence, Kansas; Athens, Georgia; and Champaign, Illinois, scored gigs by the end of 1982, as did dark L.A. blues punks the Gun Club and bright Illinois pop-rockers the Shoes. Jonathan Richman was backed by Springfield’s Route 66-ready Americana progenitors the Morells. In February 1982, Boston’s snarky Human Sexual Response slinked in.

The band that really kept the club afloat early on, though, was homegrown. “Good-looking dudes with perfect teeth,” Costello says of Fool’s Face, a skinny-tied Springfield power-pop quintet, that “would draw everyone — frat people more than the hipsters who really liked Devo.” In late ’82, Fool’s Face even played the Phi Kappa Theta’s house lawn, while 6,000 students reportedly emptied 91 kegs: “The most blatant alcohol offense that has ever occurred,” Director of Residential Life Tom Ramey scolded at the time. But when Fool’s Face headed west to L.A. in search of gold in 1984, a big-label deal never materialized.

Crow in Cashmere

Same can’t be said for Sheryl Crow, who received her Mizzou bachelor’s in music education in 1984, eventually serving as Grand Marshal of the 2003 Homecoming parade and having a performance space, the Sheryl Crow Auditorium, named for her at the Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield Music Center — and on top of all that, she was recently inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Despite Crow’s cover band Cashmere interpreting the Go-Go’s and Nena (“99 Luftballoons”) regularly at frat parties and Bullwinkle’s, they never set foot on the Blue Note stage. “I’ve told her it was all Phil’s fault,” King laughs. Costello likewise blames King. Of course, Crow wasn’t a superstar yet. In September 1980, the Missourian quoted her in a mundane piece about new students moving in: “One freshman, Sheryl Crow of Lathrop Hall, says ‘We tried moving the furniture three different ways before we could make everything fit.’”

Crow and her Kappa Alpha Theta sisters were regulars at downtown mainstay Harpo’s — where “normal, traditional Preppies go,” according to a 1981 nightlife overview in the Missourian. “The borderline, not quite sure what they’re doing, go to Bullwinkle’s, and the extremists or radicals go to By George.” Young Sigma Chi member Brad Pitt was a prep — and a member of the student-run pop concerts committee.

This was the era of the cheeky bestselling style guide The Official Preppy Handbook, whose editor Lisa Birnbach spoke at the university in 1980–’81 — same school year the Savitar yearbook included a two-page spread recommending conservative plaid skirts and “the fresh-scrubbed look that’s any frat boy’s dream” rather than fishnet stockings and too much Maybelline.

More fun in the new world

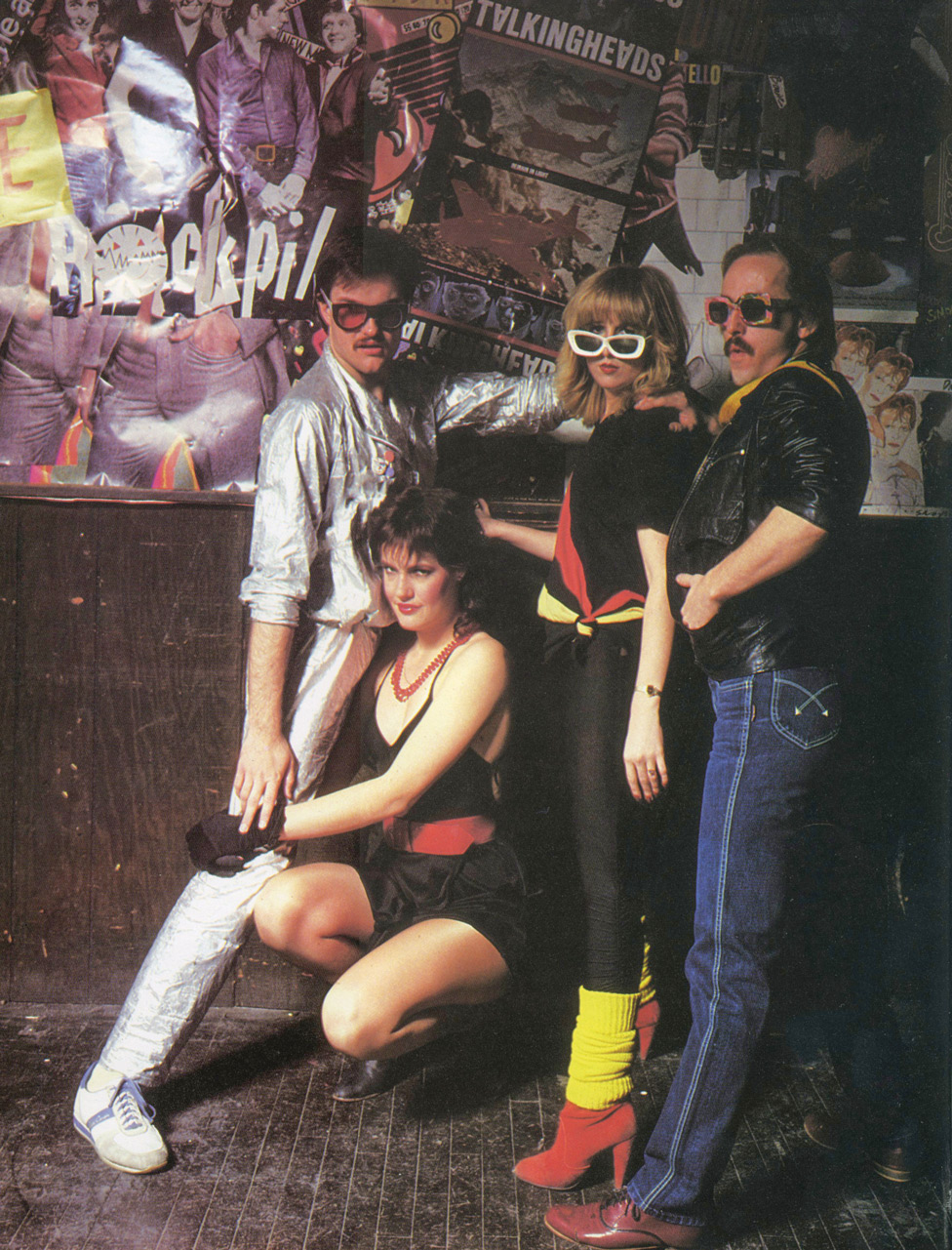

My favorite Savitar photo of the time has two severely angled young women and two incongruously ’70s-mustached young men dressed up totally weekend-new-wave in cheap sunglasses in front of a wall plastered with Rockpile, Talking Heads and David Bowie posters — clues that it’s 1980. Maybe it was taken at one of the “New Wave Nights” hosted by venues such as Studio 16 or T.W. Chumley’s. It may have even been the night DuPre swears I won a dance contest to Ian Dury’s “Hit Me with Your Rhythm Stick.”

Alternately, it might stem from the evening when magazine major and Missouri Student Association film committee member Maggie Hupp (now Fahey), BJ ’83, says that she, KCOU DJ and operations director Lisa Orf (Sher), BJ ’82, our friend Don McCoy (wearing a yellow Devo suit) and I went to By George on East Broadway. “It was a weeknight and nearly empty,” she remembers, and “when they showed [the video for] Talking Heads’ ‘Once in a Lifetime’ we got up and danced. Other patrons in the bar threw pennies at us. Which may be why we more often went to the Blue Note.” She insists I even “did the chop-on-the-arm David Byrne” move.

On Thursday afternoons through college, I traded my skinny ties for Army fatigues to receive instruction in first aid, land navigation, patrolling, firing M16s, and rappelling off the Crowder Hall roof or down a local rock quarry. Hey, at least my hair was already short — new wavers weren’t hippies, after all.

But I took covert circuitous routes from the dorm to Crowder, or maybe changed in the latrine, because ROTC wasn’t particularly the image I wanted to convey. A couple times a year we’d muster for weekendlong field exercises in Ozarks training base Fort Leonard Wood (aka Fort Lost in the Woods). Occasionally, I’d weasel out. But after completing courses in Fort Riley, Kansas, and Fort Gordon, Georgia, I was soon reporting for Signal Corps platoon-leader duty in Bad Kreuznach, West Germany. When I completed my four-year obligation, I was a captain.

Still, ROTC’s definitely not where I made my name at Mizzou. Once I hit J-School, I chronicled a wide-enough scope of phenomena for the Missourian — Christmas trees, cassettes, Missouri’s first rapper Jerry Hand, Deadheads, Muzak, myths about gender and math skills, a management professor praising newfangled “computer algorithms” — to win an annual feature-writing award. My most controversial piece in Columbia, though, involved KCOU.

Left of the dial

So let’s back up. Funded by money from each dorm resident’s activity fee, KCOU is among the oldest student-supported, -owned and -operated radio stations in the country. “Aside from our location, we had no oversight or affiliation with the university,” explains Tom Harper, BJ ’81, then a DJ for both KCOU and the mobile Discotron service. “We treated our license like it was gold. It protected us from any interference other than the FCC.”

Begun on closed circuit through phone lines to dorms in 1961, the station broadcast at 430 watts to a 10-mile radius by the ’80s. “KCOU was our sorority, our fraternity,” Merelo remembers. “It was kind of the college version of WKRP in Cincinnati,” in Propst’s estimation. “Most fun I ever had.”

The station broke several artists — Dire Straits, U2, Tom Petty — before more commercial outlets added them. In the pre-internet ’80s, college radio stations across the country were just starting to gain influence. “Our role was to expose the students to music they weren’t going to hear in their hometowns,” Merelo wrote via email. “I remember writing a scathing memo to the staff at one time, saying how too many of the shifts were sounding like [St. Louis rock station] KSHE and that our job was to open minds.”

Not always easy when, as Propst jokes, so many dorm residents in KCOU’s target audience “had four albums and three of them were by Van Halen,” and the station, by contrast, boasted of having “the largest vinyl library in the state of Missouri.” But they persevered.

Harper, now a production director for radio and podcast giant iHeartMedia, remembers eyeing a red translucent promo of the first album by British band Squeeze that somebody had slid into a ceiling light to make the hallway look cool. He’d never heard of them, but he tracked through the LP anyway, wondering: “‘Why aren’t we playing this? It’s great.’ That started the debate that we weren’t playing new music and we shouldn’t be a pale imitation of KSHE. Lots of jocks left in disgust.”

Harper’s across-the-hall Tiger Towers neighbor Brad Markowitz, BJ ’80, a DJ at KCOU, had convinced him to join the station. “The first time I put on the headphones and opened the mic, I knew I had found my future,” Harper says. “Within the year, I was the chief announcer and, with Bob Kuhlman, [BGS ’80], started ‘Rockit 88.’”

Disrupting the airwaves

This is where I come in. “Rockit 88” aired two nights a week and was devoted to new music not accessible enough for regular broadcast hours. At one point, I ended up as a guest DJ. The actual host hadn’t shown, leaving me alone in the studio with an engineer. I proceeded to play “punk funk” and early rap that KCOU otherwise avoided by artists including Rick James, Grace Jones, Funkadelic, Kurtis Blow and, especially, Prince.

This was 1981, before his Royal Purplosity had crossed over to a mass rock audience, not to mention the year he was booed off stage opening for the Rolling Stones; two summers earlier, Midwestern baseball and rock fans had set disco records ablaze in Chicago. Some months after my DJ gig, I published an editorial in the Maneater titled “KCOU Ignores Black Artists,” arguing that “the station’s just a little backward, that’s all.”

General manager Marc Chechik, BJ ’80, in a subsequent letter to the Maneater, explained how my night on the air had ended: “After a rather tumultuous evening when Chuck was guest-hosting and playing hefty portions of progressive Black music, I immediately ‘rescue’ the station by proceeding to throw him off the air. I called the music ‘disco,’ ‘trash’ and a variety of other colorful terms.” Chechik went on, though, to offer a mea culpa: “I was wrong. Dead wrong. Chuck may have radically outraged an entire listening audience, but his motives were exactly what KCOU is attempting to strive for. That, of course, is introducing new forms of music to our listeners.”

Want to survey some of the music mentioned in this story? Click on this custom playlist.

Propst claims to remember me once “coming to the station with a Prince album and saying, ‘YOU GUYS MUST PLAY THIS NOW!’” I suspect that brash demand is what got me invited on in the first place. “The controversy around your on-air gig,” Harper wrote to me, “was great. Disturbing the status quo was what KCOU was all about, but once we got popular, we sort of forgot it.”

William “Bubba” Singleton, BA ’81, one of only a couple Black DJs at the station then — not to mention, he says, the first Black member of Mizzou’s chapter of the Acacia fraternity — grew up a “radio geek” in St. Louis, to the extent that the Missourian ran a 1980 feature about his amazing knack for winning albums from radio call-in contests, on a rotary phone no less. But he says that when listening to rock frequencies in his youth, “It was rare to hear anyone of color, even Sly and the Family Stone.”

Despite such limitations, I was a loyal KCOU listener. Tuning in was educational fun. For 40 years now, in scores of mix cassettes I made for friends and bar-DJ engagements in New York, hundreds of playlists I’ve been paid to construct for streaming services, and thousands of articles of I’ve written for publication, I’ve made the sorts of connections between music that I subliminally absorbed from KCOU.

Largely thanks to the journalism school, the DJs came from across the country. This made for a wide variety of sensibilities, Propst figures; New Jerseyite Merelo, for instance, “knew all about Springsteen,” and other DJs “had been in the service — all of that came to bear.”

“We lived to impress each other with our awesome segues,” Harper remembers.

Merelo adds: “When we’d nail one, we’d squeal with delight. This was vinyl. Each song was manually ‘slip-cued’ into the next.” DJs would occasionally play the game “Follow the Leader,” Propst reports, taking turns spinning songs and trying to trip each other up. Sometimes, Harper confesses, they’d miss class because of it.

Growing up

What’s that Bruce Springsteen line about learning more from a 3-minute record than you ever learned in school? The university was the magnet, but the education so many of us accrued even outside of classrooms has served us well.

Even in the 21st century, ripples from early ’80s Columbia continue to reverberate. At iHeart, Harper has engineered live radio sessions with plenty of artists he used to play on KCOU — and a few with Sheryl Crow. Costello helped break Radiohead as senior VP of radio promotion at Capitol Records; he’s since worked as an exec at music biz powerhouse Red Light Management. After selling the club eight years ago, King bought Cooper’s Landing, a marina, campground and live music venue south of Columbia on the Missouri River. (In 2018, concert behemoth Live Nation bought a majority stake in the Blue Note.)

Whizz clerk and KCOU program director Long did radio promotions at hugely influential indie rock label SST, founded groundbreaking techno label Astralwerks and worked in A&R at a couple major labels before becoming president of New York-based music agency Knitting Factory Management. Singleton has parlayed what Propst calls his “one-of-a-kind deep bass James Earl Jones voice” into a decades-long career as an audiobook narrator, voiceover actor and host of Metromedia’s Bill Quinn Radio Hour.

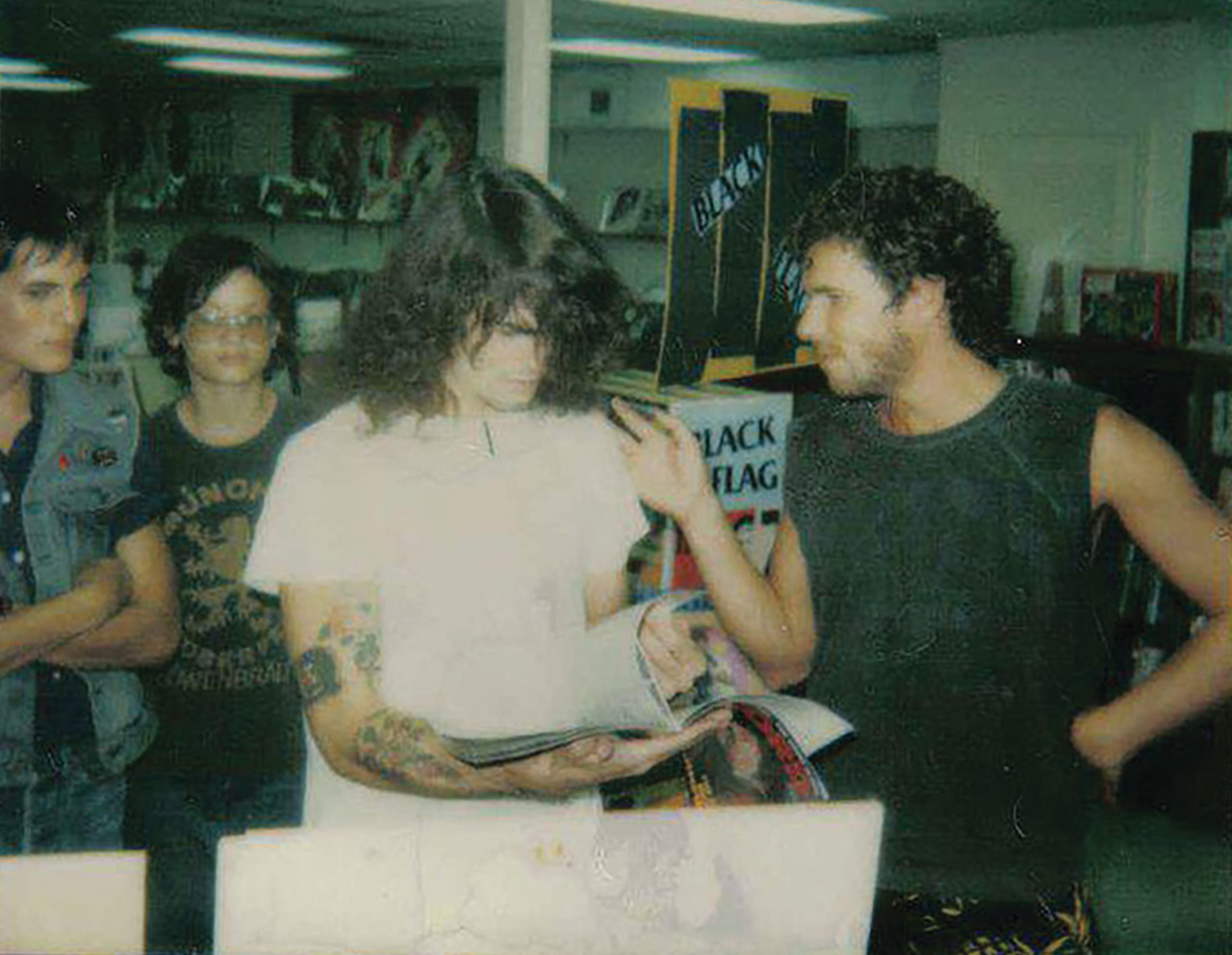

Meanwhile, after R.E.M.’s late ’82 show, the Blue Note became a key stop on the indie-label rock touring circuit, hosting Black Flag, Hüsker Dü, Replacements — the era’s entire growing gamut of American van dogs. Ultimately, everyone from Johnny Cash to Megadeth played there. Columbia was a music crossroads, in the middle of its state in the middle of the map. It hit the bullseye.

And heck, even if I didn’t stick around the Army long enough to be promoted to brigadier general like my ROTC cadet classmate Mark Spindler, I did manage to accumulate a file cabinet full of bylines and edit the Village Voice music section for seven years. Kinda wish I had that cushy military retirement pension. But has the general written four books?

About the author: Chuck Eddy’s writing has appeared in outlets including Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly and Rhapsody. A former editor at Billboard and the Village Voice, he’s the author of several books including Terminated for Reasons of Taste: Other Ways to Hear Essential and Inessential Music.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.