Published on Show Me Mizzou April 27, 2023

Story by Kelsey Allen, BA, BJ ’10

Astronomer Haojing Yan was anxious. The president and vice president were more than an hour late to a press event where NASA would release the first images from its new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope, which only sees visible light, ultraviolet radiation and near-infrared radiation, the JWST uses infrared light, enabling it to detect objects up to 100 times fainter.

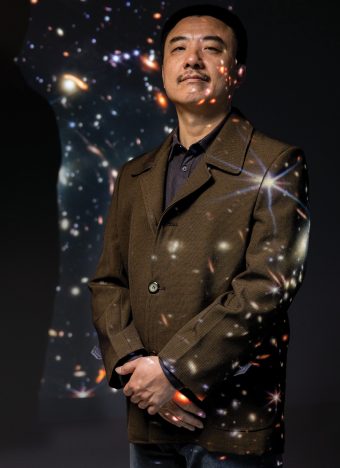

Yan had been waiting to work with data from the telescope since he was guaranteed observation time with it 21 years ago as a graduate student on a research team. Now an associate professor at MU, he’s spent his career searching for early-universe galaxies. Scientists like Yan study distant galaxies because their light — sent out billions of years ago but only now reaching us — can tell us about conditions early in the universe’s 13.7-billion-year history.

“When we are looking at a galaxy that is so far away, we are actually looking into this picture from billions of years ago,” Yan says. “This is how we can reconstruct the history of our universe. By looking at the galaxies farther and farther and farther away, we are looking deeper and deeper, or earlier and earlier, in the history of the universe.”

But Hubble can only see so far back in time — about 400 million years after the Big Bang. Although scientists knew there were faraway galaxies beyond Hubble’s observational limits, previous research suggests that the number of galaxies sharply decreases the farther back they look.

So when Joe Biden and Kamala Harris finally arrived and the deep-field image was finally displayed, Yan was shocked. Sitting in his home in Columbia, Missouri, on that sweltering July afternoon, Yan saw “something really exciting, totally unexpected,” he says. Compared to an image of the same speck of the universe taken by Hubble, the JWST image featured many extraordinarily bright red objects — and Yan thinks they’re some of the earliest galaxies to form in the universe.

In a study published in December in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, Yan reports that he and his colleagues identified 87 candidate galaxies, some of which could date back to about 13.5 billion years ago, just 200 million years after the Big Bang. These findings might force scientists to rethink how galaxies begin forming within the universe.

“It’s important and exciting news for the whole astronomical society,” says Yicheng Guo, an assistant professor of astronomy at MU whose research focuses on how galaxies were formed. “We didn’t expect the galaxies to form that early and to form that bright in the early universe. Finding the first galaxies, or the candidates, can place very strong constraints on our understanding of the whole universe.”

The galaxies are considered candidates until their distances are confirmed using a time-consuming and expensive technique called spectroscopy. In January, Yan submitted a proposal for more observation time with the JWST so he can gather this critical spectroscopic data. He’ll find out in May if his proposal is selected. But he’s confident that a majority will be confirmed as ultra-distance galaxies. At a press conference at the American Astronomical Society meeting, he even offered a wager: “I’ll bet $20 and a tall beer that the success rate will be higher than 50%.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.