Published on Show Me Mizzou Sept. 4, 2023

Story by Tony Rehagen, BA, BJ ’01

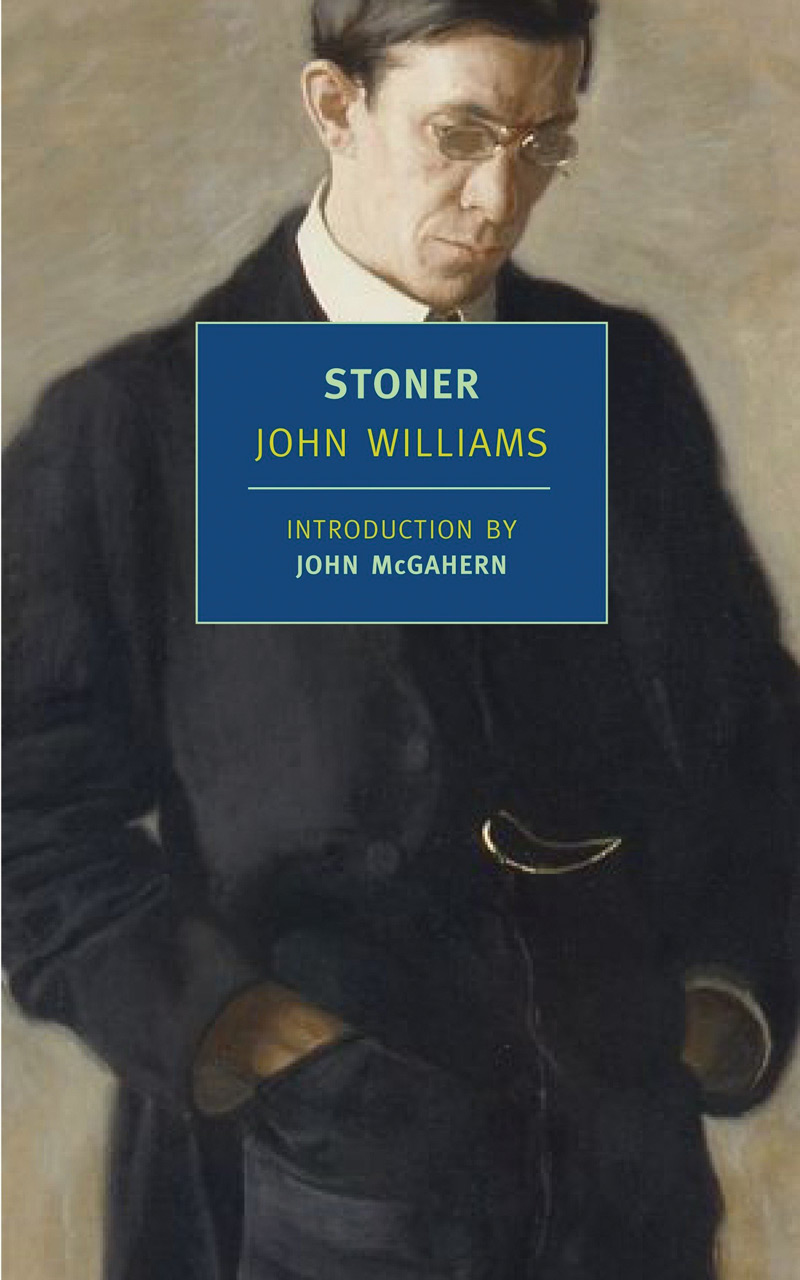

In 2013, the New Yorker reviewed John Williams’ Stoner, declaring it the “greatest novel you’ve never heard of,” a book “that sees life whole and as it is, without delusion yet without despair.” Both the Guardian and Waterstones, a British book retailer, soon named it their book of the year.

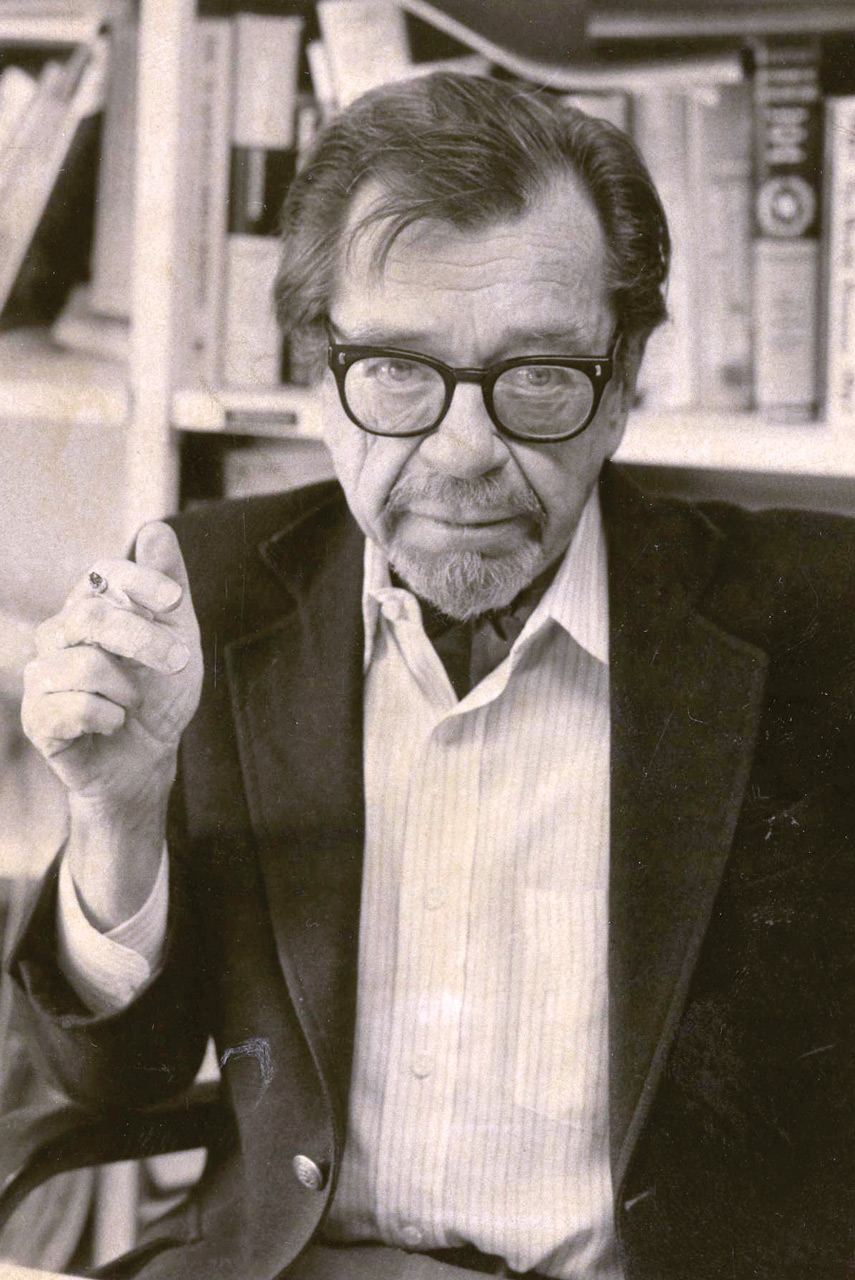

Alas, Williams, PhD ’54, was not able to relish the success — he died in 1994 — but the author no doubt would have been in equal measures pleased and chagrined by the belated appreciation of his masterpiece, which sold just 2,000 copies when it appeared in 1965. It’s now a recurrent presence on contemporary fiction bestseller lists.

The unearthing of Stoner not only renewed interest in a Mizzou alumnus but also helped introduce the literary world to the University of Missouri. The campus is more than just the setting for Prof. William Stoner’s life — it’s something of a supporting character in the work, beginning with the opening line: “William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen.”

The narrative follows Stoner as he leaves his family’s farm near Boonville (Williams spells it “Booneville”) to enroll in the College of Agriculture at Mizzou. The young man planned to attend the land-grant university to learn the latest advances in agronomy and take that skill and knowledge back to the field.

During a survey course in English literature, though, Stoner is seduced by Shakespeare’s sonnets. “He held the feeling to him as he hurried to his next class,” Williams wrote of the moments after Stoner’s awakening to literature, “and he held it through the lecture by his professor in soil chemistry, against the droning voice that recited things to be written in notebooks and remembered by a process of drudgery that even now was becoming unfamiliar to him.” Stoner eventually abandons farming to pursue a career in literary studies.

In the book’s dedication to the author’s former English department colleagues, he says that both people and place have “in effect” been fictionalized beyond recognition. Even so, the mention of Boonville and scenes of Stoner strolling past the Columns en route to his classes and later his office in Jesse Hall are instantly familiar to any Tiger, past or present.

Meanwhile, modern readers gravitate to how the book makes the seemingly insignificant jump from the page. In fact, the first paragraph is essentially Stoner’s obituary, and an unremarkable one at that: “He did not rise above the rank of assistant professor, and few students remembered him with any sharpness after they had taken his courses.” Yet Williams’ careful cadence and easy pacing compel readers to follow for 275 more pages. In the end, after watching any hope of happiness slip away from our protagonist, readers come to see something sacred in an unassuming life quietly lived.

Williams only spent a year in Columbia, during which he studied, taught and steeped himself in campus gossip and lore in a literary club of students and professors that met twice a month at Moon Valley Villa, a banquet hall that sat just south of what is now Stephens Lake Park. He then moved on to become a professor at the University of Denver, where he wrote four novels, the third of which was Stoner. In 1972, he penned his final work, Augustus, which won Williams a share of the National Book Award. But even then, wide recognition for Stoner, now considered to be his finest novel, would have to wait another four decades.

How established has it become in the contemporary canon? Stoner — which, despite its title, contains nary a mention of cannabis — has been optioned for film by lauded company Film4 and in 2017 was attached to a project by Blumhouse Productions starring Oscar-winner Casey Affleck, though work hasn’t started. Currently, Stoner is at No. 78 on Amazon’s top-selling contemporary literature and fiction list, where it sits alongside more renowned novels including David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day and The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison.

Although Professor Stoner finds little joy during his fictional life in Columbia, Mizzou does emerge from the gloom as a champion for knowledge. Early on, Stoner the student searches for reassurance about his decision to abandon the farm in pursuit of higher learning: “Sometimes he stood in the center of the quad, looking at the five [sic] huge columns in front of Jesse Hall that thrust upward into the night out of the cool grass … . Grayish silver in the moonlight, bare and pure, they seemed to him to represent the way of life he had embraced, as a temple represents a god.”

“The implication,” writes biographer Charles Shields, “is that the University of Missouri, the first university west of the Mississippi, is a kind of Athens on the edge of the wilderness.”

A Stoner guide to columbia

Across a novel set in and around Mizzou, Stoner protagonist William Stoner spends the first half of the 20th century — two World Wars, the Roaring ’20s and the Great Depression included — woven into the fabric of the university. As he, his family, students and peers do so, author John Williams, PhD ’54, paints a vivid picture of Columbia and the campus.

Here are a few of the most resonant descriptions.

On the MU Library:

[B]efore William Stoner the future lay bright and certain and unchanging. He saw it, not as a flux of event and change and potentiality, but as territory ahead that awaited his exploration. He saw it as the great University library, to which new wings might be built, to which new books might be added and from which old ones might be withdrawn, while its true nature remained essentially unchanged.

On the Quad:

Sometimes he stood at the center of the Quad, looking at the five [sic] huge columns in front of Jesse Hall that thrust upward into the night out of the cool grass; he had learned that these columns were the remains of the original main building of the university, destroyed many years ago by fire. Grayish silver in the moonlight, bare and pure, they seemed to him to represent the way of life he had embraced, as a temple represents a god.

Inside (what seem like) the Niedermeyer Apartments:

About three blocks from the campus, toward town, a cluster of old houses had, some years before, been converted into apartments … The house in which Katherine Driscoll lived stood in the midst of these. It was a huge three-storied building of gray stone, with a bewildering variety of entrances and exits, with turrets and bay windows and balconies projecting outward and upward on all sides.

Inside Jesse Hall:

He stood at the stairs that led up to the second floor; the steps were marble, and in their precise centers were gentle troughs worn smooth by decades of footsteps going up and down. They had been almost new when — how many years ago? — he had first stood here and looked up, as he looked now, and wondered where they would lead him.

At the end of World War I:

On November 11th of that year, two months after its last semester began, the Armistice was signed. The news came on a class day, and immediately the classes broke up; students ran aimlessly about the campus and started small parades that gathered, dispersed, and gathered again, winding through halls, classrooms, and offices. Half against his will, Stoner was caught up in one of these which led into Jesse Hall, through corridors, up stairs, and through corridors again.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.