Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 16, 2022

Story by Marina Shifrin, BJ ’10

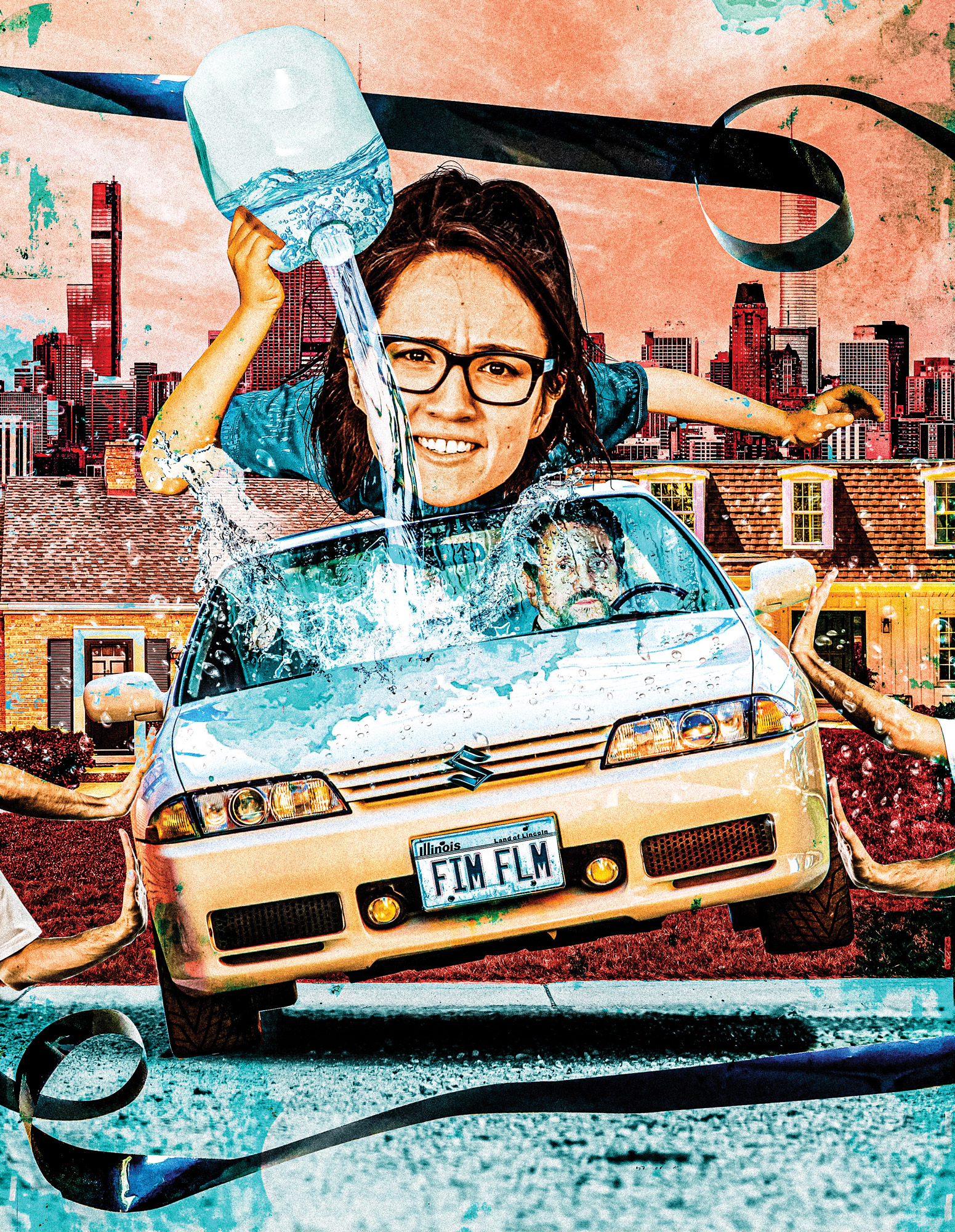

When my mother lifted me on the roof of my father’s Suzuki Swift, I broke free from the size constraints of my 8-year-old body. From somewhere below, my Uncle Fima yelled “ACTION!” and assorted family members began vigorously rocking the car.

Fighting tremors of motion sickness, I tilted a jug of water and watched as big glugs poured down the windshield. Inside his prized Swift, Vladimir, my father, forlornly stared out the window and into the lens of a Sony Hi8 Camcorder securely positioned in my uncle’s hands. Minutes later, my uncle yelled “CUT!” and I melted with relief. My job for the day was complete. I’d made it rain.

Shooting this music video with my family is one of my earliest childhood memories. Although I never appear on screen, I was always close to the action, lurking behind the camera, quietly trying to figure out what was going on.

The “world” premiere of the video, inexplicably titled Madonna, was held in front of the big box television in Uncle Fima’s living room. For 4 minutes and 35 seconds, we sat silently watching my dad’s face flicker across the TV. The credits rolled, and that’s when I saw:

“Light………………………………………………….…….…Marina Shifrin.”

Somehow, my name had made its way inside the television. Elation thrummed through my body as my family burst into applause. I clapped harder and louder than anyone.

After filming Madonna, my dad and Uncle Fima recruited a third friend, Uncle Mark (it should be noted that I dutifully call my dad’s friends “Uncle” like many Soviet children are taught), for their next project.

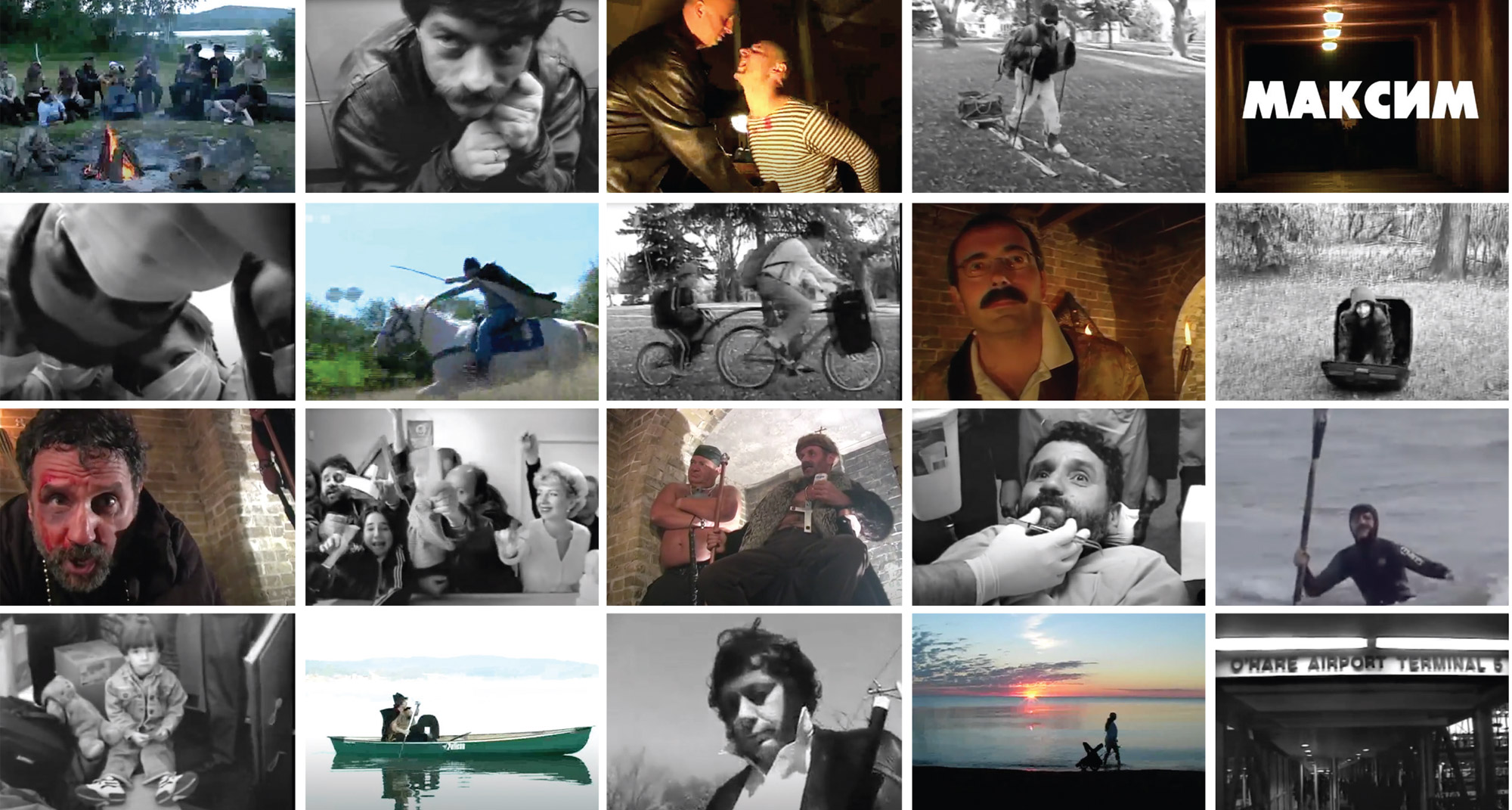

Together, the three Chicagoland men formed FimFilm, their “production company.” Unlike traditional production companies, the trio only financed their own projects, never hired any staff and always operated at a loss.

Their second film, The Assassination Attempt, a 10-minute parody of the real-life assassination attempt on Vladimir Lenin, marked the first time I was allowed on camera. When my Uncle Fima yelled “ACTION!” I couldn’t contain my excitement. I began bouncing off the walls, performing half-baked dance moves, doing everything possible to get the camera’s attention.

My uncle yelled “CUT!” and it only took one look at my dad’s face to know I’d messed up. Big. I was promptly banished to another room, where I had to sit silently for the rest of filming. It took five days of good behavior and lots of moping to regain my place in front of the camera.

Months after we finished shooting, FimFilm premiered The Assassination Attempt during a small party of friends and family. Although most of my family didn’t notice my blatant absence in the opening scenes, I shrunk in shame. That night, I vowed never to upset the director again.

FimFilm became bolder with their third movie, The Goyim Are Quiet Here, a 17-minute loose (I cannot emphasize that word enough) re-enactment of our immigration experience. This film had a narrative arc, costume changes and practical, in-camera effects — we even infiltrated O’Hare International Airport to use as an art-imitating-life backdrop for the arrival scenes.

I went full method at O’Hare, eagerly embracing my Fresh Off The Boat role. As we rode the escalators up and down (and up and down), I made sure my jaw dropped lower than my cousin Boris’ and that I always knew where the camera was because you gotta know your angles. This time, when FimFilm finished editing the movie, I appeared in every scene.

All told, my dad and his two friends shot nine films. And despite having full-time jobs, needy families and zero moviemaking experience, each year FimFilm’s movies became more ambitious and the production even costlier. However, the audience of family and friends remained the same.

If you ask my dad why he spent two decades pouring his free time, money and energy into making movies, he’ll just shrug and say, “Because it was fun.” Fun would not be the word I’d use. Although the productions were always amateur affairs, the stress-fueled pressure was as professional as it comes. To this day, I can’t watch a FimFilm movie without hearing the walls reverberate with the trio’s arguments.

Growing up on film sets for movies few would actually see is a confusing experience. When most kids returned from summer break with stories of sleepaway camp and first kisses, I struggled to explain why I spent my free time watching three aging relatives scream about which horse-drawn carriage rental was more appropriate for an 1800s period piece.

In middle school, I yearned for the kind of quaint familial experiences of my peers — living room charades, bike rides at Lake Michigan. I even would’ve settled for forced dinner table Scrabble. But my father’s imagination is so robust and insatiable that no one was spared from his machinations.

I turned 12 the year they made their fourth film, a prescient comedy titled The Olympic Chronicles.

Unlike the previous three movies, where I was desperate to be on camera, this one felt more like a chore. When my dad woke up at 5 a.m. to film a flag ceremony at Chicago’s Buckingham Fountain, I slept in. I didn’t go the day FimFilm rented an indoor pool for the swimming competition scenes because wearing a bathing suit, on camera, in front of my uncles, sounded as appealing as sucking on a fistful of pennies. I appear in one scene of that movie, and I performed with the enthusiasm of … well … a preteen.

My final performance is in Duel, a biopic about famed Russian poet Aleksandr Pushkin. FimFilm cast me as a background extra in two scenes. Now a proper teenager, but still without a driver’s license, I had no means of escaping. So I begrudgingly squeezed into the black pantyhose and shirt my mother deemed to be a ballerina outfit and slouched onto “set” — in this case, an empty bedroom with a mirrored closet. I still don’t quite comprehend why ballerinas were in a movie about a poet, but I have learned it is best not to study the plot too much.

Had I known that this would be my last opportunity to be in one of my dad’s movies, I probably would’ve savored the moment. But instead, I eagerly awaited my uncle’s “CUT!” so that I could return to privately stewing in my teenage angst.

By my junior year at Mizzou, I was too preoccupied with journalism studies to pay attention to what FimFilm was doing. That’s why, the day my dad called to offer me a catering job for FimFilm’s first-ever Golden Oscal Ceremony, I had no idea what he was talking about. I said “Yes,” nonetheless, because I have rarely, if ever, passed up the opportunity to earn $100.

I learned the Golden Oscal, not to be confused with the Oscars, was a screening-cum-awards ceremony hosted by my father and FimFilm. The only movies shown and nominated were ones FimFilm made, of course. Additionally, FimFilm thought up their own categories and self-selected all the winners. It was a deranged award show, for sure. Aren’t they all?

When my dad first offered me the gig — I’d assumed the event would be similar to the premiere parties I’d grown up with — a dozen-odd family members gathered around the biggest TV we could find, supportively applauding an odd piece of film we created together.

However, I arrived at the address, which turned out to be a suburban community center, and was shocked to see what almost looked like a movie theater. My dad and uncles had blown up posters from their own movies to give the room a hint of Hollywood. Once again, an idea of my father’s spilled out of his brain and into the world in the most delectably unexpected way.

As the audience arrived, the small vestibule quickly filled up. Twenty people became 40, then 80, and eventually, I was surrounded by hundreds of Chicagoland Soviets I didn’t recognize — everyone donning formal attire: fur coats, bow ties, cummerbunds, shimmering dresses. To this day, the Golden Oscal Ceremony is the most luxurious event I’ve ever been to, fancier than my prom.

The lights dimmed, and the crowd began to migrate into the theater. My cousins and I hung back, stuffing leftover appetizers into our mouths while cleaning up. After 10 minutes of uproarious laughter emanating from the closed double doors, my curiosity got the best of me, and I crept into the theater. I sank into a red velvet chair and watched as my dad glided across the stage like a Roomba, sucking all of the attention from the audience.

Vladimir, wearing a slick black suit and red bowtie, beamed as he took his place behind the podium. When my dad spoke, the audience listened. When he paused, they cackled. And when he finished, they clapped. Vladimir might’ve had a four-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bath in the suburbs, but the stage was his real home.

I’ve spent much of my adult life trying to figure out what inspired my father to begin making films in his 40s. It wasn’t for the fame. He never tried to sell the movies, and this was a decade before social media would make virality feasible. It certainly wasn’t for the fortune because, and I hate to belabor this point, there is no money in movies written by and starring middle-aged Soviet immigrants. Yet year after year, something brought my father back to that spiral-bound notebook, where he’d scribble all his burgeoning cinematic visions in big Cyrillic letters.

Growing up with a father who processes the world through writing taught me to do the same. I have hundreds of my own ideas scribbled into copious notebooks. And just this past March, I, too, had the opportunity to turn one of my ideas into a short film. Twenty-five years after my mother hoisted me on top of my dad’s Suzuki Swift, I began to understand the motivations behind his hobby.

Standing in the middle of my chaotic living room packed with a production crew, my father’s perspective began to crystalize in me. To quote Vladimir, “It was fun.” Not only was it fun, but I got to experience the supernatural feeling of physically standing inside a world I created with my words.

My family’s history is riddled with difficult plot points — political unrest, government-sanctioned abuse of power, forced emigration. Vladimir created fantasy worlds where assassination attempts were hilarious and being a refugee was even funnier. His movies made a difficult life easier to digest, and I wanted to do the same.

During the shoot, I kept having these surreal moments where I could feel myself embodying my father’s commanding persona. I walked around adjusting props, making jokes, sweating through difficult scenes, channeling Vladimir’s semidelusional sense of confidence. Despite my years of fighting for fierce independence from my parents, I’d ended up exactly like my father: escaping the monotonous nature of adulthood with little more than a pen and venturesome friends.

Last month, I was in Chicago for the first time in years. At my parents’ kitchen table, the indents from my old geometry homework still visible in the varnish, I sat behind my dad as he watched a rough cut of my short film on the old desktop they inexplicably keep in the corner kitchen. Minutes into the movie, my dad leaned closer and closer to the screen until I was certain he might fall inside.

Because the film was unfinished, there were no credits at the end, just an empty black placeholder. In the dark reflection of the computer screen, I could see my dad’s face crumple into tears. “Wow,” he nearly whispered, spinning around to face me, “Wow.”

My father turned around to give me a hug. “Wait!” my glass-eyed mom yelled before promptly disappearing into the dining room. A few seconds later, she returned with a bottle of whiskey and three shot glasses. It was the best premiere party I’ve ever been to.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.