Published on Show Me Mizzou April 20, 2022

Story by Tony Rehagen, BA, BJ ’01

For any student, college is just the beginning of their careers, and it’s no different for student-athletes, even the superstars. No matter when or what they played while at Mizzou, these MU Athletics Hall of Famers all went on to greatness — on the field and off.

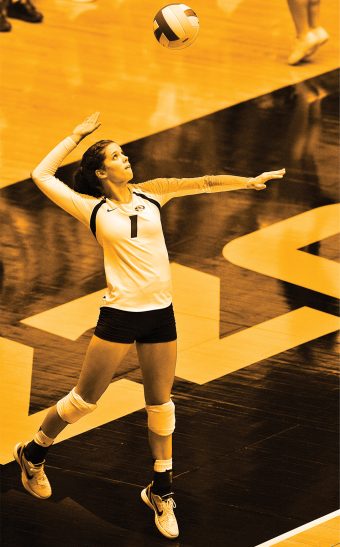

Molly (Kreklow) Taylor

Volleyball

Class of 2013

Inducted 2019

It’s common enough for world-class athletes to have family ties to their sport, but Molly Taylor’s roots in volleyball run much deeper than usual. Taylor, BS HES ’13, is in her fifth year as assistant coach at Mizzou, where her husband, Josh, has been head coach since 2019. The two were hired by Taylor’s uncle and aunt, Wayne and Susan Kreklow, the legendary coaches who brought Taylor to Mizzou as a prized recruit in 2010.

Taylor’s relationship with the game began with her mother, a former Division I athlete, who was head coach of the high school team where Taylor grew up in Delano, Minnesota. “I was in second grade, playing with my siblings in the gym or hitting the ball with the high schoolers,” Taylor says. “Growing up, my friends were playing with dolls and tea parties, but I just wanted to play volleyball. I never got sick of it. It’s the sport that I learned to love from my parents.”

If there were any notions of nepotism when Taylor arrived at Mizzou to play for her aunt and uncle, she quickly spiked them into the hardwood, winning AVCA Central Region Freshman of the Year. By the time she graduated, Taylor was one of the top players in the program’s history, a two-time All-SEC first-team setter, All-American and the face of the first team in conference history to go undefeated during the regular season.

After graduation, Taylor realized her childhood dream of making the U.S. women’s national team, where she first met her future husband, then a member of the men’s national team. The two then went on to play professionally in Europe and Asia before the pull of family brought them back to Columbia for good. Josh took over as head coach when the Kreklows retired in 2019, and Molly continued as assistant coach. In November 2021, the two gave birth to their first child, a daughter named Oakley.

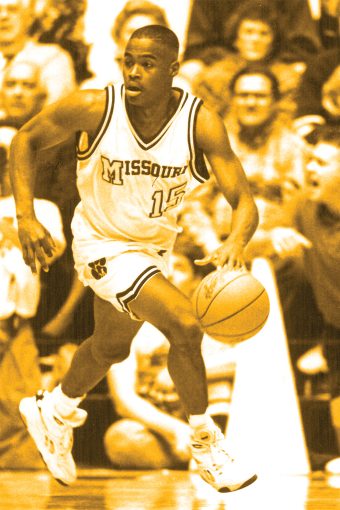

Melvin Booker

Men’s Basketball

Class of 1995

Inducted 1999

Today, Melvin Booker is about as close as anyone can come to being a professional father. In addition to his day job as an NBA talent agent, he is also the representative, trainer and biggest fan of his son, NBA superstar Devin Booker. While it might sound like a cushy gig, Booker’s current position is the result of many sacrifices he’s made since leaving Mizzou.

Go back to 1997, three years after MU, when Booker, Bus ’95, was playing for the NBA’s Golden State Warriors. He had played little more than 25 minutes in 16 games that year for Golden State, his third team in two years, and his career was at a crossroads. He could continue chasing the goal of being an NBA regular who had started in Columbia, where he was the fifth-highest scorer in school history, Big Eight Player of the Year and first-team All-American. Or he could leave for more money playing in Europe. Devin had been born the previous year, and with a family to support, Booker decided to pack up and move abroad.

Fast-forward to 2008, when, after successful stints playing in Italy, Turkey and Russia, Booker was back in Milan. Meanwhile, Devin was nearing high school, and it was apparent to everyone that his skills on the court were beyond those of other kids his age. That’s when Booker decided to retire from playing; move back to his hometown of Moss Point, Mississippi; accept a coaching position at his high school alma mater; and bring Devin with him. “I had a two-year deal on the table back in Italy,” Melvin says. “But I could see my son’s own passion for the game. It was time to get back to him and be a father and a coach and help him develop.”

After one year at Kentucky, Devin was drafted to the NBA, where he is a two-time All-Star for the Phoenix Suns. Booker retired from coaching to be Devin’s advocate, trainer and shooting partner whenever the son called. Now, Booker has decided to become an agent and use his experience helping his son navigate his career to help others. “I’m mentoring kids and guiding families to make decisions that are best for them,” Booker says. “I feel like that’s what I was put on this earth to do.”

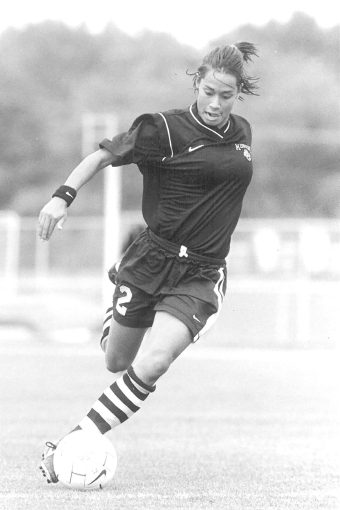

Nikki Thole

Soccer

Class of 2001

Inducted 2006

Almost all student-athletes enter college with dreams of going pro and having a long, successful playing career, and Nikki Thole came closer to realizing that fantasy than most. But Thole, a second-team All-American and holder of virtually every scoring record in Mizzou women’s soccer history, now thinks it took her nearly 20 years to find her true calling: homeschool teacher to her son.

When Thole, BS ’01, arrived at MU, the women’s soccer team was only in its second year of existence. She emerged as the face of the program, earning All-Big-12 honors in each of her four seasons here. At the time, there were few opportunities for women to play soccer professionally, so Thole jumped at the chance to play ball first semiprofessionally in Colorado and then for a pro team in England. She returned to the U.S. to try out for an upstart women’s professional soccer league, but she didn’t make the cut. “I decided it was time to get a big girl job,” Thole says.

Using her degree in parks and tourism, Thole took a position with St. Louis County parks and then the city of Des Peres, where she fell in love with her co-workers and the job of running sports leagues, camps, swim lessons, and group exercise classes for adults and especially kids. She worked her way up in the role for 16 years until COVID-19 hit in the spring of 2020. She wanted to keep her son home but worried that virtual learning wasn’t the best fit, so she started homeschooling him. When she saw how well he did — and how much she enjoyed teaching — she decided to continue. “We still do PE 40% of the time,” says Thole, jokingly. “And we play soccer, outside and in the basement, on our breaks.”

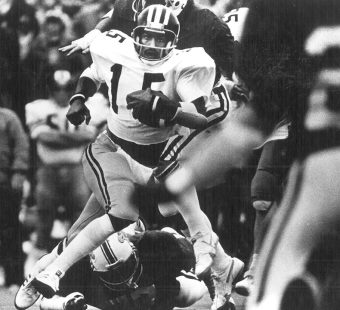

Bill Tobin

Football

Class of 1963

Inducted 1997

Bill Tobin has been evaluating NFL talent for more than half a century. He has scouted dozens of professional footballers and helped draft Hall of Famers Walter Payton and Marshall Faulk. And he chuckles at the notion that the use of analytics is some revolutionary new thing in sports. Tobin, BS Ed ’63, M Ed ’67, says he and his fellow scouts always used statistical data to predict performance — they just also factored in the eye test as it compared with their personal experience in having played the game. “Now we have all these fancy words for it; now we use computers,” says Tobin, currently in talent development for the Cincinnati Bengals. “But I don’t think they compare to the mind.”

During his three years as a Tiger halfback and kicker, Tobin certainly made an impression on his coach, fellow MU Athletics Hall of Famer Dan Devine. After Tobin finished his pro career in the NFL and Canada and a brief stint as Mizzou assistant, Devine hired his former player as a scout for the Green Bay Packers in 1971. Thus began a long career in scouting and assessing talent for the Packers, Bears and Colts, where he rose to general manager. After a year in Detroit, Tobin settled into a front-office position with the Bengals, where he offers his insight on players to another boss with whom he has a personal relationship — his son, Director of Player Personnel Duke Tobin.

At age 81, Tobin still enjoys his job but is spending more time in the stands watching his grandchildren play football and basketball. “That’s my true joy and relaxation right now,” he says. “I think sports is a very important part of a young person’s life.”

Kris Schmidt

Softball

Classes of 1988 and 1991

Inducted 1999

The life of a college athlete is all about repeatedly training, studying, practicing and preparing so that you’ll be ready for whatever you might encounter on game day. Kris Schmidt, BSW ’88, MSW ’91, found that this approach applied directly to her career after Mizzou softball — except her “game day” was when she was assigned to protect the lives of some of the most powerful people on Earth.

After setting school records for hits, batting, average and putouts; making three All-Big-Eight teams; and being named an All-American, Schmidt played semipro ball, coached at Mizzou and played for the U.S. national team. Eventually, she decided to represent her country in another way, as a member of the U.S. Secret Service. “The mission is what it sounds like,” Schmidt says. “You are there to ensure the health, safety and security of the protected. You constantly train, plan and prepare for game day, which is every time you are with the protectee, whether that be at the White House or traveling across the country or the world. It’s a coordinated team effort, working with your fellow agents, uniformed division officers, the military, and local and state law enforcement.”

Over 23 years, Schmidt protected presidents, vice presidents and foreign dignitaries from Tony Blair to Nelson Mandela. She’s worked all over the world and above it aboard Air Force One and Marine One. Throughout her career, she thought she was prepared for anything — except for what she felt during her first midnight shift at the White House. “I was standing at the top of the grand staircase right outside the private residence,” says Schmidt, who retired from the Secret Service in September 2017. “Looking at the presidential portraits in the historic building, thinking about how amazing it was to be there, standing in history — it was really cool. Then I told myself, ‘OK, OK. Back to reality. Time to focus on the job.’ ”

Phil Bradley

Baseball and Football

Class of 1982

Inducted 1990

The key to advocating for yourself and your fellow players is having a realistic idea of your value. That might be why Phil Bradley is a natural fit with the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), where he has been a special assistant for 22 years.

Bradley, BS BA ’82, first came to Mizzou on a football scholarship and proved his worth by quarterbacking the Tigers to three straight bowl games and himself to three Big Eight Offensive Player of the Year honors. Ask any fan from that time, and they’d probably only remember him from his work on the football field. But Bradley’s ambition was always to play Major League Baseball. “What limited my hopes of professional football was my size,” Bradley says. “In the 1980s, the quarterback position was the 6-foot-4, 240-pound stereotype. Back then, it was all about big, strong-armed quarterbacks. Now, it’s more about athleticism and creativity. In 2021, I could’ve checked the boxes that would’ve allowed me to play.”

Bradley passed up a chance to play football in Canada to enter the MLB draft. He was selected as the first pick of the third round by the Seattle Mariners, where he would eventually become an All-Star outfielder. He spent seven years between four MLB teams, including the Baltimore Orioles, which suddenly traded him to Chicago after Bradley publicly rejected a contract offer as “a humiliation.” He spent the following year in Japan before returning to play briefly in the minors. In 1994, he retired to coach college baseball at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, where he also taught sports history. Five years later, Bradley was contacted by the current executive director of the MLB player’s union. “The MLBPA is mostly lawyers who don’t understand the nuances of being a player,” Bradley says. “They needed someone to thread the needle — someone who understood what the players needed. I could do that.”

Bradley has settled into the role of international rep. He travels the world — from the Tokyo Dome to Cuba to the Olympics in Australia and the Field of Dreams in Iowa — to make sure that the fields and facilities are suited to the players’ health, comfort and safety standards, looking out for what’s best for them, just as he did for himself.

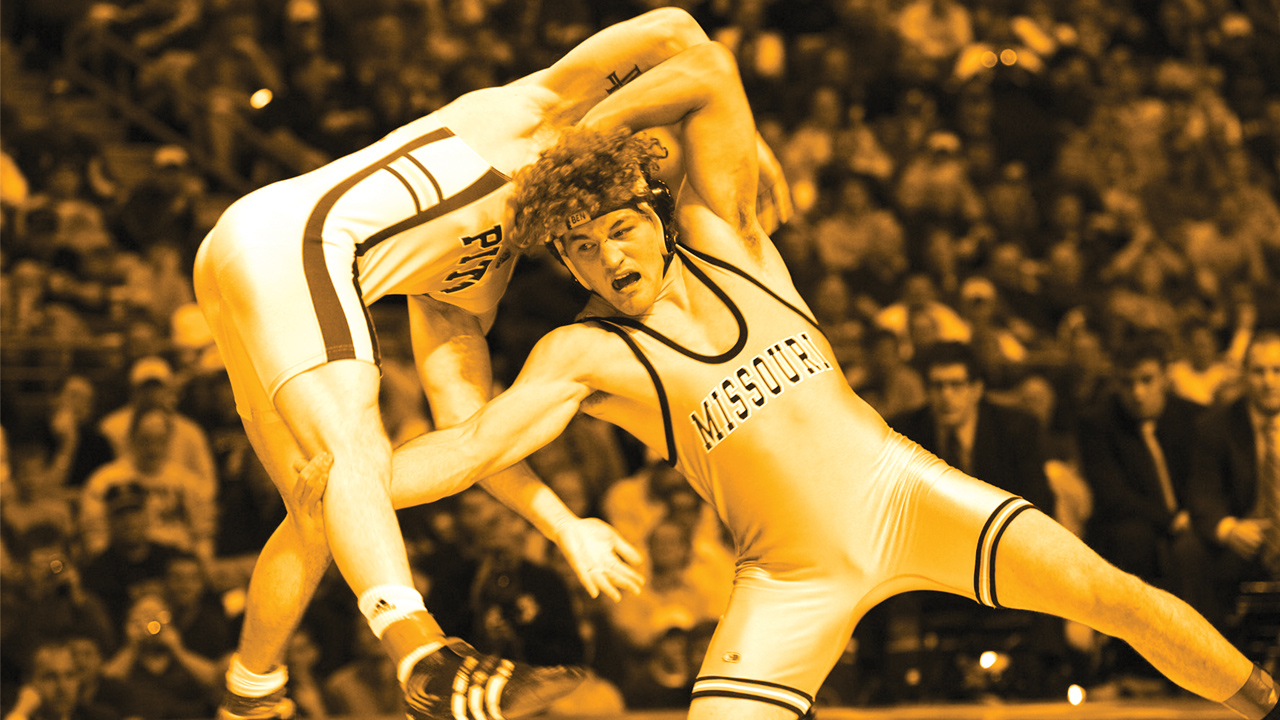

Ben Askren

Wrestling

Class of 2007

Inducted 2011

There is perhaps no greater gap between the college and pro levels of a sport than there is in wrestling. Amateur wrestlers compete and improvise on the mats, while professional wrestlers entertain in predetermined matches in the ring. Some grapplers make that jump, but most, like Ben Askren, transition to other combat sports, like mixed martial arts. And few have done it as effectively as Ben Askren, BA ’07.

Following one of the most dominant careers in Mizzou history, in which the four-time All-American went a combined 87–0 in his junior and senior years, winning the NCAA titles in 2006 and 2007, Askren wrestled in the Beijing Olympics and briefly coached at MU before jumping into the MMA octagon. Askren won his first 17 matches and grabbed the Bellator Welterweight Championship and the ONE Welterweight title. “From a technical standpoint, wrestling and MMA are different,” Askren says. “But from a mental and training perspective, they’re almost the exact same thing.”

When he felt he ran out of challengers in 2017, Askren retired and devoted himself to the wrestling schools he and his brother had started in 2011 in their home state of Wisconsin. He came back briefly in 2019 to fight in the Ultimate Fighting Championship and recently even tried his fist at boxing YouTube personality Jake Paul. But he says that, in addition to co-hosting some wrestling podcasts, he is now dedicated to passing on his knowledge of amateur grappling and freestyle wrestling. “I think coaching is great,” Askren says. “You get kids to believe in themselves. That’s a powerful thing to watch and see happen.”

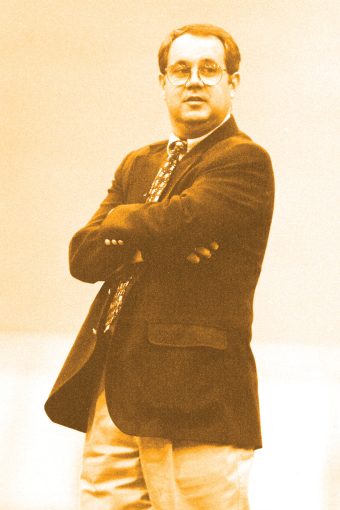

Rick McGuire

Track and Field Head Coach

Inducted 2015

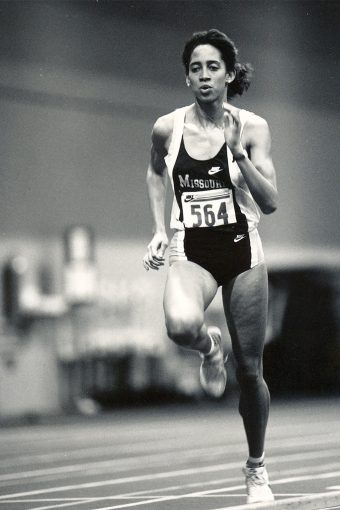

Natasha Kaiser-Brown

Track and Field

Class of 1990

Inducted 1994

It’s rare enough for the paths of two Hall of Famers to cross. So, what are the odds of a pair of inductees crediting each other with the entire trajectory of their legendary careers?

Today, Rick McGuire is an icon, not only synonymous with Mizzou track and field but also an international leader in the field of sport psychology who still lectures and runs workshops on positive coaching. But in 1984, he was a fledgling coach and recruiting staff of one trying to sell would-be student-athletes on an MU program that didn’t even have a real track. “We had a ring of crushed red dog shale around the football field,” McGuire recalls. “In the 1950s, that was the standard; but in the 1980s, everyone had synthetic tracks — except for the University of Missouri. I was recruiting kids who were picking between Missouri and Stanford or Princeton or Duke and having to find a way to show them a reason to choose Missouri. That’s where Natasha came in.”

At the time, Natasha Kaiser-Brown, BA ’90, was one of the most highly sought-after high school sprinters in the country. She had her choice of colleges to attend. While all the other coaches who came to visit her and her family in Des Moines, Iowa, sat on their couch and talked about nothing but track, McGuire tried to sell them on all that MU offered. “He and my parents talked for hours about the university and what my experience would look like as a student,” Kaiser-Brown says. “My mother was a teacher. When she heard that, she was intrigued.”

So was Kaiser-Brown. She says she chose MU mainly because of McGuire, and together, the two made history. Kaiser-Brown went on to win five individual conference titles, NCAA All-American honors six times and Big Eight Female Athlete of the Year in 1989. She still owns the school indoor record in the 400-meter dash. She went on to win silver in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics (where McGuire was on the U.S. national team’s coaching staff) and gold in the 1993 World Championships.

Meanwhile, McGuire made Kaiser-Brown part of the foundation of his burgeoning program. In addition to showcasing the school to recruits, he could now point to Kaiser-Brown as an example of what was possible for student-athletes at Mizzou, both on the track and off. Over the next three decades, he brought in some of the most decorated athletes and teams in any sport in school history, turning MU track and field into a nationally recognized program.

McGuire also kept in close touch with his former athletes, including Kaiser-Brown. And in 2000, he was able to repay all Kaiser-Brown had done for his coaching career by jump-starting hers. At the time, she was one of McGuire’s assistants at Mizzou, and the two were driving to Iowa for the funeral of a friend, the former women’s track coach at Drake University. On the trip, McGuire urged his protégé to apply for the now-open position at her hometown school. She did, and so began a 16-year career as head coach of the women’s and eventually men’s track program at Drake.

The two careers again intersected in 2016, when McGuire urged Kaiser-Brown and her husband, fellow track star and coach Brian Brown, MPA ’95, PhD ’05, to come back to Mizzou, where McGuire had been his doctoral adviser. She is now in her sixth year as associate head coach to the Tiger track and field team, and she says she models much of her approach on that of her mentor. “Anybody can write workouts and stand there with a stopwatch,” Kaiser-Brown says. “But can you coach the person? It takes time. A lot of coaches don’t have the time. It’s easier to yell at them and intimidate them into getting what you want. That’s abusive — and temporary.”