Published on Show Me Mizzou August 25, 2022

Story by Mara Reinstein, BJ ’98

By the time James Draper’s schoolmates were joining the Cub Scouts, he was already immersing himself in the world’s creativity. That was in Lebanon, Missouri, where, his sister Ruth jokes, the nearest thing to a notable artifact was a Civil War cannonball. Even so, Draper went on to a distinguished curatorial career at the celebrated Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. When he died in 2019, his gift enabled the museum to buy what is now one of its most remarkable holdings.

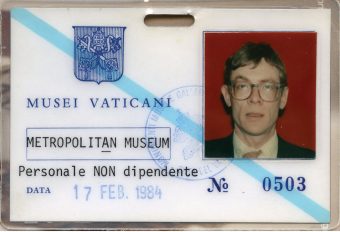

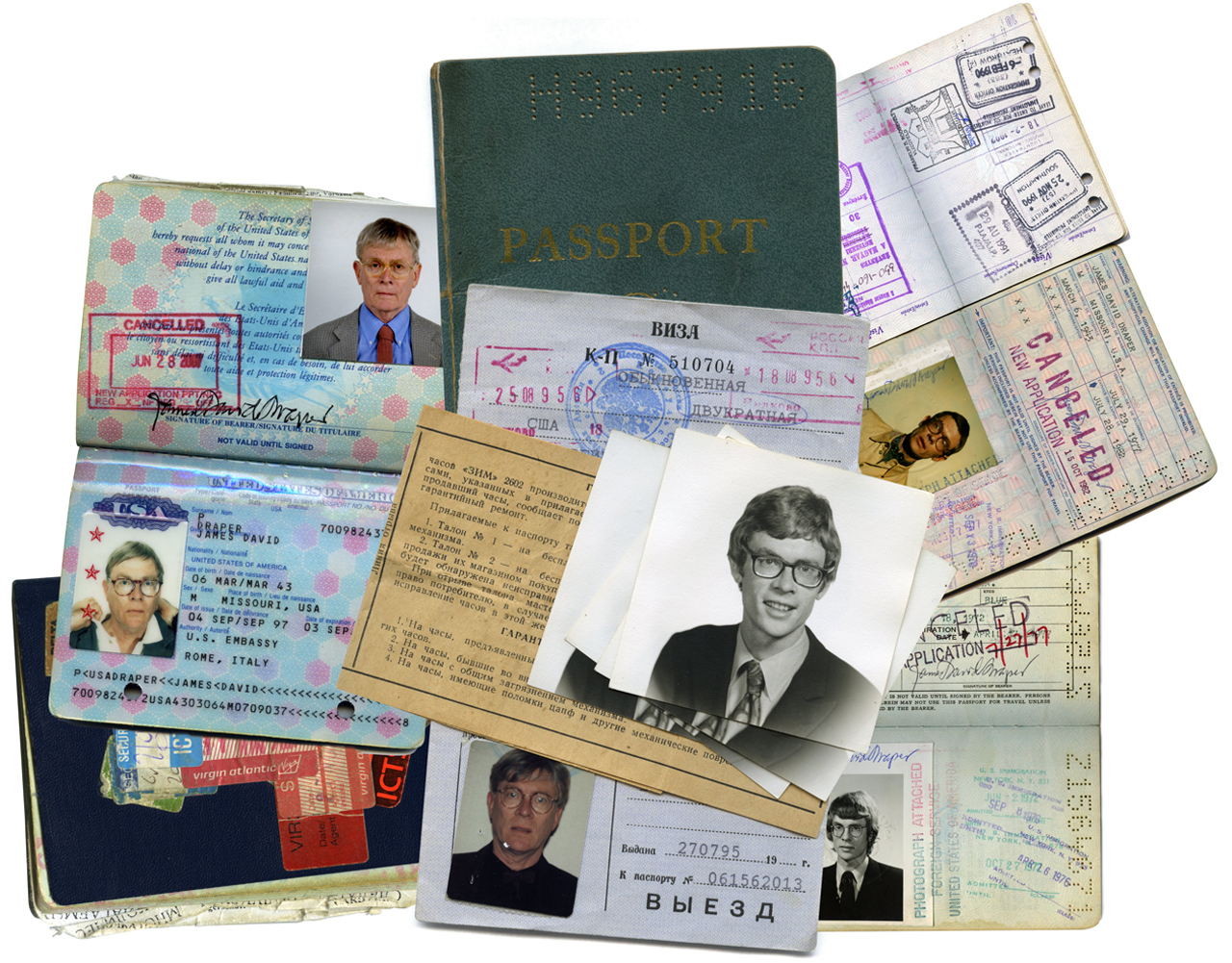

One of the most meaningful artifacts in the history of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City will never be on display. It’s also worth a grand total of zero dollars. But for the staff in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, the work — actually, a Met purchase report from 2003 — is priceless. It was written by James David Draper, who, at the time, was the longtime and highly respected Henry R. Kravis Curator in the department. Draper, BA ’65, had his heart set on a bronze roundel that dated back to the Italian Renaissance of 1500. When it finally came up for auction at Christie’s New York, he was determined to obtain it for the Met — and, per protocol, filled out the necessary paperwork in advance. He was outbid, and the documentation got lost. That is until Draper’s original request was recently fished out from the museum counsel’s office.

His former colleagues were gobsmacked by what they read. “Jim was soaring on the wings of eagles when he wrote that report,” says Denise Allen, a curator in the department. She points to his response to the first question, for which he had to state the reason for recommending the piece. “He wrote, ‘This is the most thrilling Renaissance bronze to appear on the market in ages,’ leaving no doubt as to how he came down on the issue. That was typical Jim.”

Nineteen years later, the dream of this beloved curator and proud Mizzou art history graduate has been fulfilled in the most wonderful of ways.

Draper, you see, adored the Fifth Avenue landmark that he called his home away from home for 45 years. Although he retired in 2014, he stayed on as a curator emeritus for European sculpture and reported to his office nearly every day. Upon his death in 2019 at age 76, he made a large financial bequest to the Met on behalf of his foundation earmarked for acquisitions within the department that he helped shape. The money was put to use in February, when the Met spent $23 million to buy the roundel from a gallery in Britain — making it the museum’s second-largest purchase ever, per The New York Times. It now hangs in Gallery 536, with Draper’s name imprinted on the credit line.

“We decided that acquiring the roundel that he had been so excited about would be the best way to honor his gift as well as his tenure at the Met,” Allen says. “It’s rare that you can speak for someone, but I know that he would be pleased.”

Gotta have art

Speaking of eye-popping numbers, how about this one: 2. That’s the age a young Jimmy Draper first showed interest in art in his blue-collar hometown of Lebanon, Missouri. “He’d get in the kitchen cabinet and take off the papers of all the cans and then draw pictures on the back,” recalls his younger sister, Ruth Rebmann. “Even as a baby, he’d teethe on my daddy’s fancy fountain pen.”

As his two sisters tell it, Draper’s passion for beauty was a gift from the gods. “None of us have any idea where it came from because there’s just nothing like it in our family,” says his older sister, Betsy Erb. Indeed, though their family boasts impressive lineage — their great-great-grandfather Joseph McClurg was the governor of Missouri from 1869 to 1871 — no Drapers have ever carried the art gene. “Our daddy ran a stave mill, which is about as opposite of a curator of sculpture at the Met as you can get,” Rebmann adds.

While Rebmann was outside playing ball with her dad, Draper holed up in his room listening to opera. He checked out every art-related book from the local library, becoming so obsessed with the subject that the elderly librarian had to special order periodicals to feed his voracious appetite. He slept with encyclopedias and could rattle off facts about obscure artists, even though his family preferred camping to art museum field trips. Not that Lebanon had one, anyway.

By fifth grade, Draper had already determined his future. For a homework assignment in which he had to predict his career, he declared that he was going to be a curator either at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The teacher presented his mom with the paper after he had made good on his promise. “She told Mother that it was the first time she’d ever had a student be so specific about a career and then do it,” Erb recalls. “Usually kids would say they wanted to work on a farm.”

But first, college: His sisters, who both studied early childhood education at Southwest Missouri State, surmise that Draper chose Mizzou because it was the closest university with an art department. As an art history major in the 1960s, Draper would sometimes be the only student in his class.

He succeeded, of course. He excelled in his language classes, too, and earned a prestigious Woodrow Wilson fellowship. But Rebmann jokes that he was lucky to receive his degree, as an algebra professor took pity on his woeful math skills and passed him. With a D-minus.

Big Apple bite

It’s easy to invoke the lyrics of “(Theme from) New York, New York” when detailing Draper’s next chapter. Yes, he left Missouri in 1965 to be a part of it, earning a master’s degree at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts and later a doctorate. His little-town blues melted away. And in 1969, he took a job as a curatorial assistant at the Met — which would ultimately make him top of the heap/king of the hill/a-number one in his field.

“He was so good at his job because he had a beautiful eye,” Allen says. “When he looked at art, he could be focused and put it in a context. He’d pick up a bronze and judge the quality of its design and modeling. He was also incredibly charming and was really good at rallying the troops.” Seconds Ken Soehner, the Met librarian, friend and co-worker of 27 years: “Jim worked very hard and took great pleasure from just looking at objects. But No. 1, he loved what he did.”

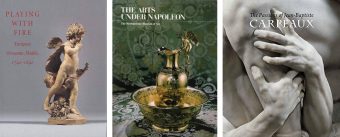

As a curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Draper traveled extensively. During a trip to Madrid with his sisters and their families, “Jimmy took us to museums and led us past all the tour groups so he could find the specific paintings that he wanted to see,” Erb says. On his own turf, he prided himself on his exhibits and acquisitions and was quick to give private tours to visitors during off-hours. Erb still remembers her reaction when she approached the Met’s famous steps in 1978 and saw the massive banner for the “Arts of Napoleon” exhibit hanging outside. “My jaw about hit the street!” she says. “This was his first solo exhibit, and I knew it was a big deal. I didn’t realize it was that big.”

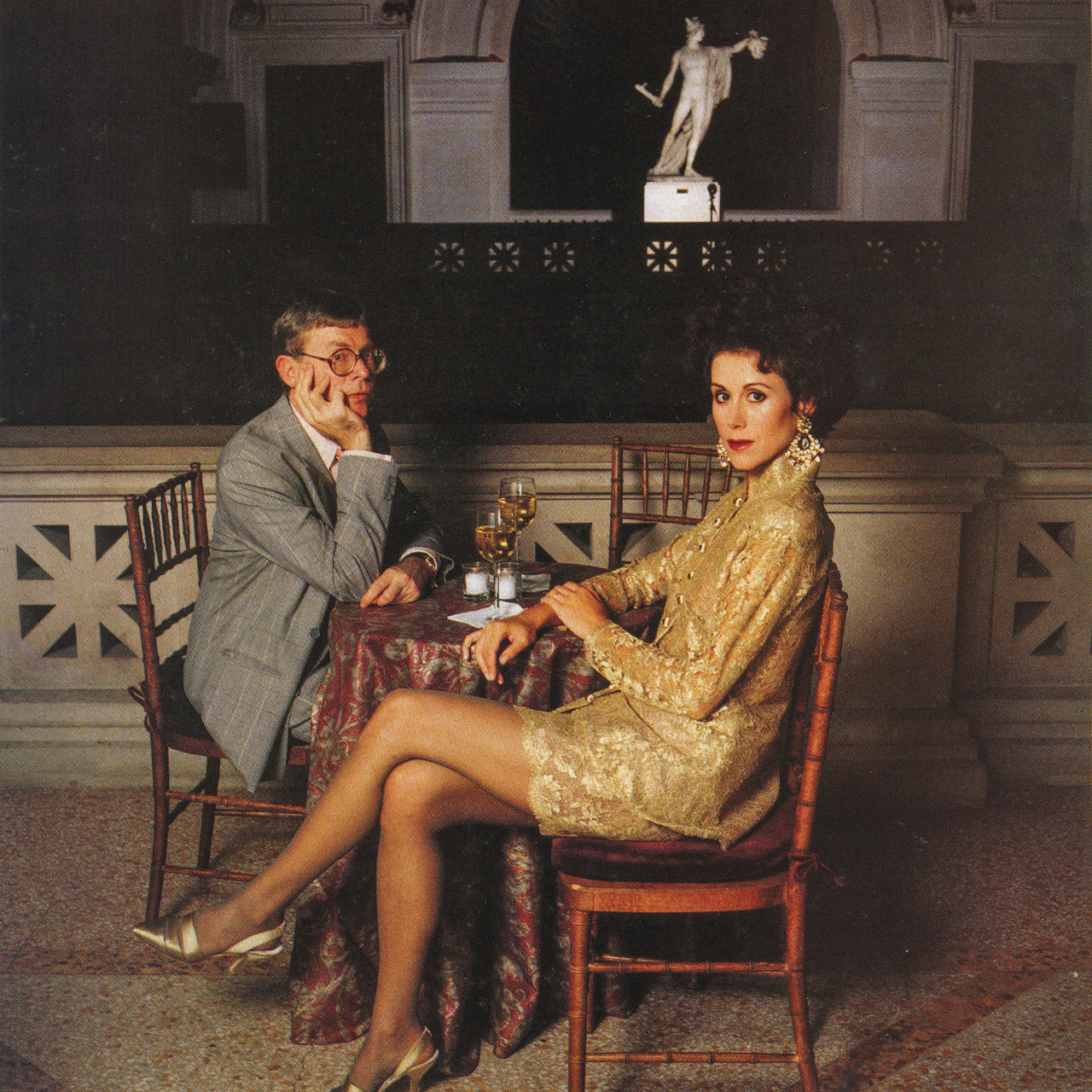

With his longtime partner, fur trade heir Robert Isaacson, Draper also established the Isaacson-Draper Foundation that enabled the department to purchase objects, sponsor museum exhibitions and put on concerts. Exulting in the good life, “He bought a coffee table that cost $45,000,” Rebmann says. “I was an elementary school teacher and my salary was $8,000!” She notes that he would even buy a first-class plane ticket for his pug.

Yet he was deeply proud of his Missouri roots. “Jim was very attached to his background,” Soehner says. “He was happy to have his experiences growing up in Lebanon and was always positive and good-natured about it.” If anything, his humble beginnings helped him become a popular figure within the sophisticated hub of his universe: “He had an important job in an important place, but he never wore his rank on his sleeve.”

A great legacy

Draper eventually did come home to Missouri in 2019 so his family could take care of him as he lay sick with cancer. Upon his death that November, nobody in his inner circle was surprised that he left 37 pieces of his personal collection to the Met as well as his sizeable fortune. “He didn’t have any children, so the museum was like his baby,” Erb says. “He really loved it.”

And his colleagues knew it. That’s why they prioritized purchasing the one-of-the-kind Italian Renaissance-era roundel. Crafted by Italian goldsmith and sculptor Cavalli, who worked for the Gonzaga court in Mantua, it’s embellished with gilding and silver inlay. Allen explains that the bronze roundel is extra-exquisite because it was made to be hung on a wall like a painting (as opposed to being a free-standing sculpture). It’s also derived from a direct and unique cast and features a complicated composition of Roman mythology figures Mars, Venus, Vulcan and Cupid.

Despite Draper’s enormous spend limit at the auction back in 2003, he was outbid by a Saudi prince. “It became clear at the auction that he was bidding against somebody for whom money meant nothing,” Allen says. The roundel stayed out of sight for more than a decade, save for the two years that he lent it to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In 2019, five years after the sheikh’s death, his son decided to sell it.

Draper never did speak of the object that slipped from his grasp, by the way. But he never forgot about it. Allen says that when she helped clean out his office, she found the ill-fated Christie’s auction catalog. His handwritten forensic-like observations were scrawled all over the margins. “It told you everything you needed to know about Jim,” she says.

And now that the roundel is on view to all Met visitors, it’s a fitting coda for someone who, despite his posh surroundings, liked to think of himself as just a man from Missouri who followed his dream. “He’s a real success story,” says Rebmann. “We’re all terribly proud of him.”