Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 16, 2022

Story by Tony Rehagen, BA, BJ ’01

When Mizzou men’s basketball Head Coach Dennis Gates arrived in Columbia after landing the job in March 2022, one of the first things he had to do was re-recruit his inherited roster. Every new head coach experiences a transition period as the players recruited by the old regime weigh their suddenly less certain futures. But we’re adapting to the age of the transfer portal, through which student-athletes can jump from school to school on little more than a whim, without the consequence of sitting out for 12 months or losing a year of eligibility.

Many of last year’s Tigers had already entered the portal by the time Gates was hired. If he couldn’t convince them otherwise, more were sure to follow. So, before Gates could hit the recruiting trail to build a new team, he had to first make his pitch to the remaining members of the one he inherited.

For Gates, this entailed more than meeting the players and visiting with their families. It meant sitting alone or with his assistants in front of a screen for hours on end. He wanted to see the tape, needed to watch last year’s games, focus on each individual player and look beyond the traditional stat sheets. Searching for more granular data — hard numbers that he felt would help him unlock a player’s full potential — he was convinced that not only would he be prepared to coach up the Tigers who decided to return, but he might also have something extra to entice players who fit into his system to stay.

To Gates, 42, data is much more than a mere recruiting tool; it’s an ethos. Over the past decade, advanced analytics — the use of mathematical models to predict player performance and in-game outcomes — has consumed professional basketball and is steadily encroaching on the college game. Gates is at the forefront of this collegiate movement, building his coaching staff, his roster and even enlisting an outside analytics firm, HD Intelligence, to help optimize every Tiger play and player who hits the Mizzou Arena hardwood this winter.

“Analytics is the way of the world,” Gates says. “The numbers steer you in the right direction. They help you make decisions as a coach and help players eliminate risk and put themselves in the right position to succeed.”

In other words, Gates is betting that by valuing quantifiables like player efficiency rating, true shooting percentage, and rebound rate over mere points score or assists, he can boost numbers in the most meaningful column on his team’s ledger: wins.

In some ways, Gates believed in analytics before the buzzword was ever uttered in a locker room. In fact, he might have been an adherent without even realizing it.

Growing up in Chicago during the legendary 1990s Bulls teams, Gates was far from the only kid obsessed with basketball. But in retrospect, he now realizes that he watched those NBA games differently than most. Like everyone else, he was in awe of Michael Jordan, but he was also curious about why Jordan made the decisions he did. Why did he take the shots he took? How was he able to increase his free-throw rate? Why did he always drive to the right-hand side?

Gates began drawing up plays in Coach Phil Jackson’s famous triangle offense. Eventually, he was making shot charts for the Bulls and their opponents, especially Larry Bird and Magic Johnson. “I was preparing for this moment,” he says. “I knew I would be a head coach.”

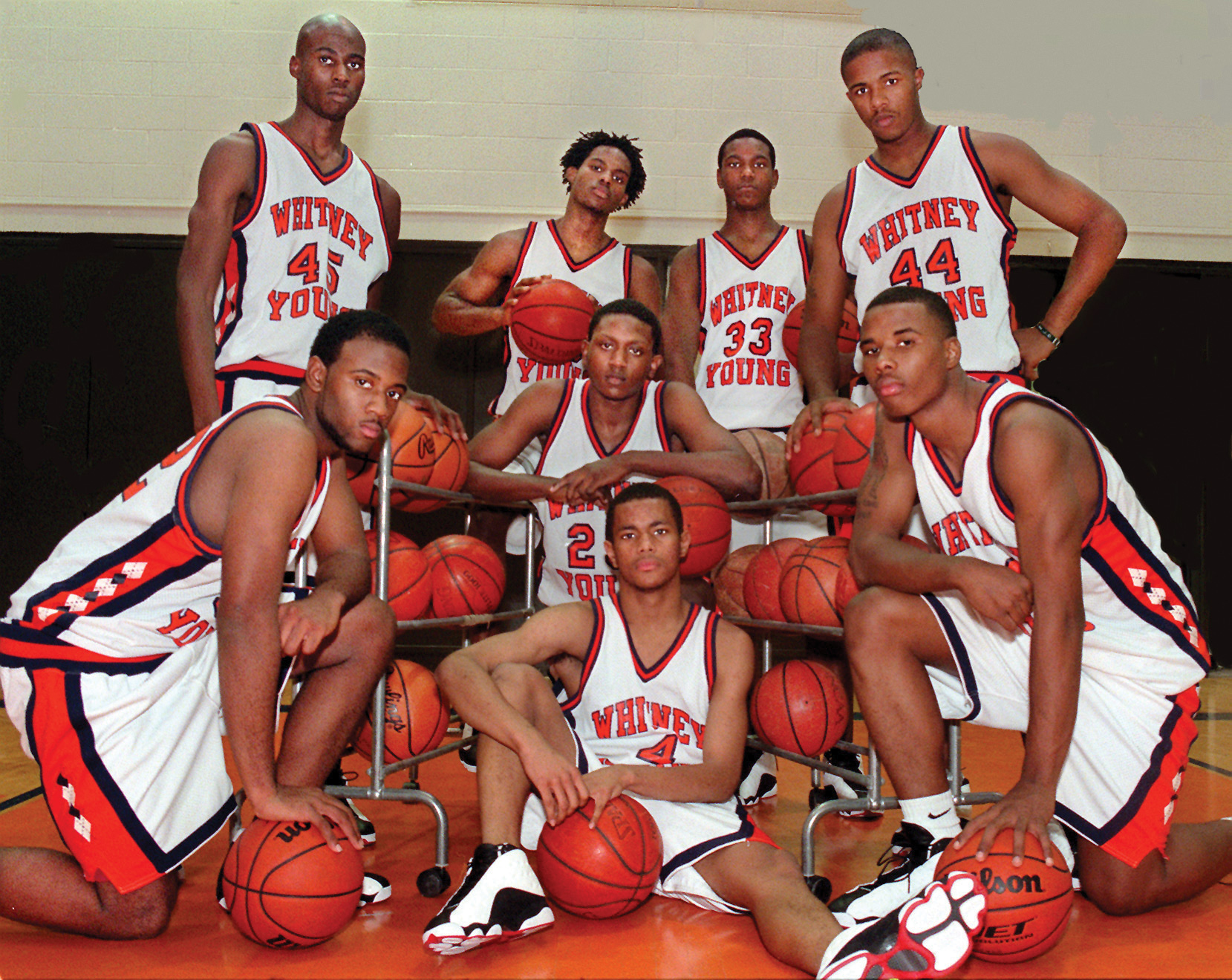

But first he was a highly touted combo guard at Whitney Young High School who was recruited by none other than Mizzou’s Norm Stewart. Gates instead chose the University of California, Berkeley, where, in addition to being a three-year team captain, he was also a two-time first-team Pac-10 All-Academic. He graduated in three years with a bachelor’s degree in sociology, pursuing his master’s in education during his fourth year of eligibility as a player. In 2002, he won the Pac-10 Medal of Honor, given to the conference’s top graduating student-athlete.

That same year, Gates took his vast knowledge of the game straight to the NBA, where he was a skills development coach for the Los Angeles Clippers. He worked with young players on the court and in the video room and kept in-game statistics, specifically plus/minus (PM), a then-new stat that showed how the team performed — outscoring (plus) or being outscored (minus) while a particular player was on the court. This number would then be used to determine in-game substitutions. “The NBA was just transitioning to the analytical approach,” Gates says. “My foundation was set.”

After a year in LA, Gates began his collegiate coaching climb. He started as a graduate assistant at Marquette and Florida State, then got on as a full-time assistant coach at Cal, Northern Illinois and Nevada. In 2011, he returned to Florida State, where he would settle in for much of the next decade. At the time, institutional application of analytics and formal analytics departments were still considered too expensive and time consuming for college basketball. Gates still applied his analytical approach, but he also honed his other coaching skills, like building relationships. And this applied to more than players.

Michael Fly was an assistant coach at Florida State before Gates arrived. In fact, Fly left in 2011 as part of the regime that Gates’ staff was supplanting. So, he was a little surprised when his replacement reached out to ask for advice. “It was odd at first,” says Fly, who is now Gates’ director of scouting and analytics at Mizzou. “He didn’t call me a lot, but when he did, he would FaceTime me.” Fly adds with a laugh: “It was usually early in the morning. The last thing I’d want was to be onscreen, but he wants to connect when he’s talking. It showed me how creative he was.”

At Florida State, Gates connected with a lot of players and families the same way. He helped lure top-100 players, including four straight top-15 ranked recruiting classes, providing the foundation for four NCAA Tournament berths, three Sweet 16s and one Elite Eight appearance. By 2019, Gates had caught the attention of Cleveland State, which hired him as its head coach after spending the previous two seasons at the bottom of the Horizon League.

Among the first players Gates recruited was Ben Sternberg, a local community college transfer. Sternberg had only made two starts at Lakeland Community College and didn’t have the grades to play in the NCAA. But basketball was his life. Gates saw something in him and brought him on board at Cleveland State as a student manager while he worked on his studies. Sternberg watched as Gates taught his players and staff about much more than basketball.

“He’d wake us up early in the morning and take us out to teach us how to change a tire,” Sternberg says. “Even as a manager, he treated me with respect, checked on my family and asked me how I was doing. He barely even knew me, but he believed in me. Coach Gates changed my life.”

Sternberg watched from the bench as Gates won a share of the Horizon League Coach of the Year, despite finishing with a 11–21 record. By the following year, Sternberg had improved his grades and was playing for a Vikings team that went 19–8, winning the conference and going to its first NCAA Tournament in more than a decade. Gates won 20 games in 2021–22, his final year at Cleveland State, earning a second postseason berth. He did it not only by recruiting the right players but by building their trust. He made them believe that he would make them better through analysis and reliance on numbers.

“We followed his lead,” Sternberg says. “We all saw his IQ. Whatever Coach tells us, we follow.”

A lot of people outside of sports, and even some old-school insiders, hear the word “analytics” and envision a coach as a pure statistician attempting to divine some deeper truth out of a sea of numbers, charts and equations. Data is at its heart, but it is not a cold, robotic science. “You also have to trust your eyes,” says Fly, who went on to be head coach at Florida Gulf Coast before joining Gates at MU. “You look at the numbers, use the analytics tools and charts, but then look at the actual games and ask, ‘Do the numbers equal what I see on film?’”

For instance, among the first tapes Gates watched after accepting the Mizzou job was that of Kobe Brown. What he saw was a standout upperclassman who had worked his way up from being a highly touted freshman to a stalwart junior who made every start and averaged 12.5 points and 7.6 rebounds per game. But through his analytical approach, Gates calculated potential for much more.

Gates checked stat sheets and wondered why Brown’s 3-point percentage was lower than it should have been for a shooter of his caliber. He looked at where Brown was taking his shots. Was it from the point or wing, which are higher percentage shots, or down in the corner, which are lower percentage? Gates watched for player possession, the amount of time Brown held the ball, and noticed that a lot of the shots Brown was taking beyond the arc were catch-and-shoot, which are statistically less likely to land. He also looked at Brown’s assist rate, observing that when Brown held the ball in 3-point range, he often looked to pass it off rather than shoot. Gates tracked when Brown was taking and making his 3s — was it earlier in the game, after coming off the bench, or after a timeout when he had fresher legs? “Kobe is already a good player,” Gates says. “This will help him become a more efficient player.”

Gates’ analytics may well be the key to Brown and his teammates becoming more productive players. It might be the key to re-establishing the Tigers as a perennial NCAA Tournament team. The coach, though, understands that research and data-crunching are useless if the players don’t trust him. Analytics didn’t convince Fly to join Gates’ coaching staff as an assistant after a successful career as a head coach in his own right. Sternberg didn’t stop to do the math before following his coach from Cleveland State to Mizzou. And numbers had very little to do with convincing Brown to stay.

“The first thing he told me was, ‘If I’m not invited to your wedding, I didn’t do my job coaching you,’” Brown says. “That’s when I knew it was more than just a job to him. He doesn’t just want to use me as a tool to win basketball games. He wants to watch me grow as a person. He is a big numbers guy, but he doesn’t believe numbers define who you are.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.