Published on Show Me Mizzou April 20, 2022

Celebrating a sesquicentennial

Ever since the days when steam engines powered industry, Tiger engineers have stoked the nation’s economy and made lives better by putting science to work. Today, hundreds of College of Engineering alumni hold CEO positions worldwide, making it one of the largest producers of CEOs in the country. “The college has been quietly but successfully developing industry leaders and transformative innovations for 150 years,” says Noah Manring, the college’s dean and Ketcham Professor.

Manring had served in various leadership and teaching roles at the college for more than two decades when he was appointed dean in April 2021. He is at work on his third book — Opportunity, Genius and Entrepreneurship: A History of Modern Engineering. The working title, like his plan for the college itself*, draws inspiration from the past and energy from a vision of what’s possible.

The pace of change keeps increasing, yet the college maintains its reputation for leadership in research and education. In its labs, a range of research includes the development of new energetic materials, medical tests and genomic sequencing techniques that make precision treatments possible. And in its classrooms, students get a top education exploring fields as diverse as geospatial intelligence, robotics and cybersecurity. “Our students engage with the world when they study with us, and they have abundant opportunities to develop and hone leadership skills,” Manring says. Aspiring engineers can participate in more than 50 student organizations while they grow professionally and personally by collaborating with students and professors across disciplines.

Manring takes pride in all things engineering. “People take technology for granted and don’t understand how indebted they are to the engineers who build roadways, purify the water we drink, make air travel possible and who have given us the cell phone and other products that have changed our world.” Tiger engineers have a proud place in this pantheon, he says: Versed in theory, rehearsed in research and primed to lead, they have always taken their places in a future they help design.

*Read the dean’s strategic plan at engineering.missouri.edu/about/strategic-plan.

A campuswide 3D printing lab

The practice of 3D printing has made huge leaps in the past decade, both in terms of what these printers can reproduce and in the accessibility of this technology to the masses. The same is true for the College of Engineering’s 3D Printing Research & Experiences Lab, which is now open to students, faculty and researchers across campus to gain experience with these state-of-the-art tools.

In fall 2021, all MU students were given the option to take an elective course on 3D printing in the lab, which was formerly known as the Rapid Prototyping Education and Application Network. Students are also encouraged to access the lab and work with its faculty on capstone and class projects. Outside of class, the Mizzou 3D Printing Club, a student-run extracurricular organization that develops projects from inception to implementation, is renewing efforts to recruit members from all disciplines, departments and degree programs. “We want to act as a pipeline for getting students into that lab with some fantastic industrial machines that you can’t find anywhere other than a university or a business,” says Chadwick Bettale, student president of the club. “And as engineers, it’s also nice for us to have that diversity and different viewpoints.”

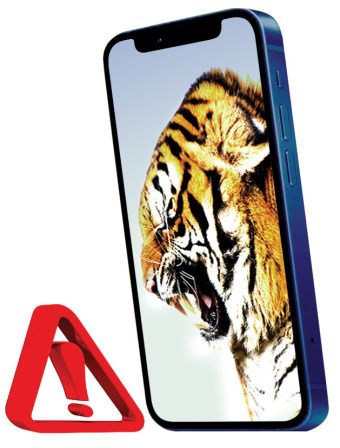

Making smartphones warier

Making smartphones warier

When you’re on your computer, cybersecurity is never far from mind. There are passwords, biometric scans and multifactor authentication. But when it comes to smart devices, including everything from our phones to app-controlled home thermostats, we take security for granted. That’s why the National Security Agency recently issued a two-year $500,000 grant to the College of Engineering to develop an add-on security feature for smart devices that learns from past cyberattacks to better respond to attacks in the future. “All of these devices connect to a gateway before they connect to the cloud,” says Prasad Calyam, associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science. “We want to know if we can update software on that gateway that can help us understand the threat landscape and create effective defenses.” Right now, the way we do things is pretty static. What makes the MU solution unique is that it seeks out new threats before they affect the devices. “This is an active defense, not antivirus or a firewall, which are passive,” Calyam says. “Our gateway software actively monitors the behavior of the device and adapts the defense based on the threat landscape.”

Art goes VR

Fang Wang, associate teaching professor in the Information Technology Program, focuses on helping students explore the burgeoning fields of virtual reality and augmented reality. Last spring, she led students in working with the State Historical Society of Missouri and the MU Museum of Art and Archaeology to put together an interactive virtual reality (VR) art exhibit of 98 paintings, many not previously on display. “Without this digital technology, these works are just hidden in some dark room,” Wang says. “This isn’t just some high-res scan. This is an immersive experience — almost like visiting a real museum.”

Fang Wang, associate teaching professor in the Information Technology Program, focuses on helping students explore the burgeoning fields of virtual reality and augmented reality. Last spring, she led students in working with the State Historical Society of Missouri and the MU Museum of Art and Archaeology to put together an interactive virtual reality (VR) art exhibit of 98 paintings, many not previously on display. “Without this digital technology, these works are just hidden in some dark room,” Wang says. “This isn’t just some high-res scan. This is an immersive experience — almost like visiting a real museum.”

The interactive museum debuted at the Together for ’21 Fest celebrating Missouri’s 200th year of statehood last year. Visitors were able to put on VR goggles and explore the collection within a virtual gallery.

“This was a great project to allow students to put their skills to use in a real-world application where people could download and consume the content,” Wang says.

Next, Wang will help students work in extended reality, including photogrammetry and motion-capture capabilities, as director of the Collaborative Research Environments for Extended Reality Lab.

MU undergrad teaches robot new tricks

When Trevontae' Haughton first got the opportunity to work with Spot, the robotic quadruped developed by Boston Dynamics, the doglike robot had already done everything from detecting gas leaks to searching for missing persons to performing tricks for audiences. But Haughton, a junior in the Information Technology Program, noticed something about Spot that graduate students, faculty and professional developers hadn’t: It didn’t come with user-friendly instructions. “The manual was like a Harry Potter book — pretty hefty,” says Haughton, who first worked with Spot as part of the Missouri Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation. The program links STEM students from underrepresented populations with undergraduate research opportunities. “To help people get acclimated, I made a few documents about how to power him on, turn him off and replace the batteries.”

When Trevontae' Haughton first got the opportunity to work with Spot, the robotic quadruped developed by Boston Dynamics, the doglike robot had already done everything from detecting gas leaks to searching for missing persons to performing tricks for audiences. But Haughton, a junior in the Information Technology Program, noticed something about Spot that graduate students, faculty and professional developers hadn’t: It didn’t come with user-friendly instructions. “The manual was like a Harry Potter book — pretty hefty,” says Haughton, who first worked with Spot as part of the Missouri Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation. The program links STEM students from underrepresented populations with undergraduate research opportunities. “To help people get acclimated, I made a few documents about how to power him on, turn him off and replace the batteries.”

Haughton is now working with the Ameren Callaway Plant nuclear facility to train Spot for autonomous inspections, potentially entering hazardous environments where humans cannot go. Haughton says it’s just the start of a future for him in robotics. “I want to work with more advanced robotics, maybe even build a robot of my own,” he says. “The possibilities are endless.”

New tech in the NICU

When it’s a matter of life or death, of course, you want to be as exacting as possible. But many NICU nurses caring for premature babies, for whom too much or too little oxygen can cause brain damage and other fatal or life-altering conditions, must manually turn a knob, watch a blood-oxygen monitor and literally try to dial in the correct amount of air for each child. But now Roger Fales, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, and collaborators have designed a device that uses a microcontroller to do the same job with precision, automatically. Fales compares the effect to that of cruise control in a car, allowing the driver to maintain the same speed no matter the terrain. His innovation is currently in clinical trials at MU Health Care and in Florida.

Jost award will help power NextGen

Enthusiasm is high for NextGen Precision Health and its interdisciplinary approach to advancing health care. And the College of Engineering is more than pulling its weight in that collaborative effort. In December, MU announced a $2 million gift from alumnus Jerry Jost to establish the Jerry L. Jost Endowed Chair in Chemical Engineering, a post that will enable Mizzou to recruit and retain a talented researcher to join NextGen and assist professors in the chemical engineering department.

Jost, BS ChE ’70, is founder and president of Jost Chemical, which makes purity specialty chemicals, such as salts for food. He is a longtime supporter of the college and is a member of the Chemical Engineering Academy of Distinguished Alumni and has served for more than a decade on the Chemical Engineering Industrial Advisory Board. Jost said in a release announcing his gift that the endowed chair would give the chemical engineering department “an opportunity to hire another faculty member that can play a key role in the NextGen research effort.”

Future-proofing supply chains

The pandemic has changed our outlook on everything from health care to education to the workplace. A Mizzou engineering team took the opportunity to model ways of making the supply chain more resilient. “Industries have dealt with individual disasters, like a tsunami in Southeast Asia or a factory fire in Europe,” says Ron McGarvey, associate professor of industrial engineering and public affairs. “But a worldwide disruption like COVID-19 is unprecedented.”

The team’s proposed model, published in the International Journal of Production Research, tries to build in responsiveness by looking at 10 potential pandemic scenarios of varying scale and scope. They lay out suggestions for manufacturers at various points on the supply chain, including setting up sourcing agreements with suppliers in multiple geographic locations, adding facilities and building up redundancy in inventory. “One of the biggest changes in the supply chain over the past 30 years is a reduction in inventory,” McGarvey says. “Companies don’t want capital tied up in inventory. But you lose something when you lose that inventory — you lose flexibility.”

Engineering eldercare

For Marjorie Skubic, professor of electrical engineering and computer science, developing health monitoring devices is deeply personal work. Her elderly parents lived in South Dakota, and Skubic was the closest of her siblings, charged with periodically checking in from 600 miles away.

So, for her mother’s 93rd birthday, she installed a home monitoring system. Skubic’s systems help older adults live independently by picking up signals — sometimes hints as subtle as a change in gait or sleep patterns — that might indicate something is wrong. Those signals are relayed to health care providers to ensure clinicians can spot and treat problems early. Skubic has seven patents, and her inventions are used commercially in senior living facilities all over the U.S., with plans for international installations. For her career accomplishments, she was recently named a Curators Distinguished Professor, MU’s highest honor for faculty. But she can trace much of her inspiration to two of her earliest research subjects — her parents.

“I was trying to figure out how to help them stay in their own home, and they agreed to be research participants,” Skubic says. “I understand on a personal level the impact that this work can make because I saw it myself.”