April 7, 2021

Contact: Eric Stann, 573-882-3346, StannE@missouri.edu

It’s a health crisis often hidden in plain sight.

While binge drinking behaviors — drinking alcohol to a blood alcohol concentration level of 0.08% or higher — have been studied before, relatively little research has focused on people’s behaviors and the consequences surrounding “extreme” drinking, or drinking alcohol to a blood alcohol concentration level of more than 0.16%. Now, using a five-year, $2.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, addiction experts at the University of Missouri from the Department of Psychological Sciences hope to provide a more accurate picture of why people engage in extreme levels of drinking using a combination of portable breathalyzers and a smartphone app, along with laboratory data.

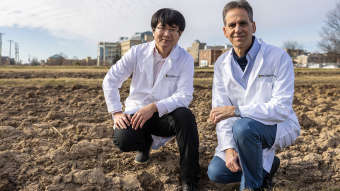

Tim Trull, a Curators Distinguished Professor and Byler Distinguished Professor of Psychological Sciences, said this new method will allow researchers to study participants both in a laboratory setting and also in the real world. Trull, the principal investigator on the grant, believes the team will be able to get an accurate representation of people’s drinking habits.

“This project will allow us to see, in a relatively natural way, what kinds of factors seem to influence whether or not someone drinks at all, or drinks to excess,” Trull said. “Some factors we are looking at range from biological, such as genetics, to more environmental, such as hanging out with friends or going to a bar or a restaurant.”

Traditionally, scientists have gathered information on people’s drinking behaviors by relying upon people who self-report their own behaviors. However, Denis McCarthy, a professor of psychology and co-principal investigator on the grant, notes that the data gathered by this reporting method is not always reliable.

“There is a lot of attention on binge drinking, but it’s not the most alcohol that people consume,” McCarthy said. “Someone who has five drinks in a two-hour period might also have 10 drinks another time. Getting information from people as they are drinking is the only way we can get an accurate report of what’s going on during these extreme drinking events. If we try to ask them later, in retrospect, the more alcohol they have drank, the less likely they are to accurately remember.”

Trull said the digital information they will gather will not contain any personally identifiable information about the study participants. He hopes the team’s findings, which will be analyzed on a population, not individual, level, could help inform future public health interventions.

“Alcohol use disorder and generally drinking excessively are huge public health issues,” Trull said. “This study is important because we are gathering real-time data on what factors may influence whether or not somebody is prone to overusing substances, while they also acknowledge the potential negative consequences of their actions.”

This project will help address one of Missouri’s most prevalent and long-standing addiction problems — alcohol abuse — which is a major focus of the Missouri Center for Addiction Research and Engagement, or MO-CARE. The center coordinates the work of addiction researchers across the University of Missouri System working to meet the needs of Missourians affected by addiction through innovative research, enhancing remote access to care and training the next generation of addiction-treatment providers.

More than 14 million American adults have a medical condition called “alcohol use disorder,” including nearly 300,000 Missourians. Binge drinking and heavy alcohol use can contribute to and increase someone’s risk for developing this condition, which is considered a brain disorder by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. These behaviors can also lead to an increased risk of developing other health problems such as chronic diseases and various cancers.