Nov. 1, 2021

Contact: Deidra Ashley, ashleyde@missouri.edu

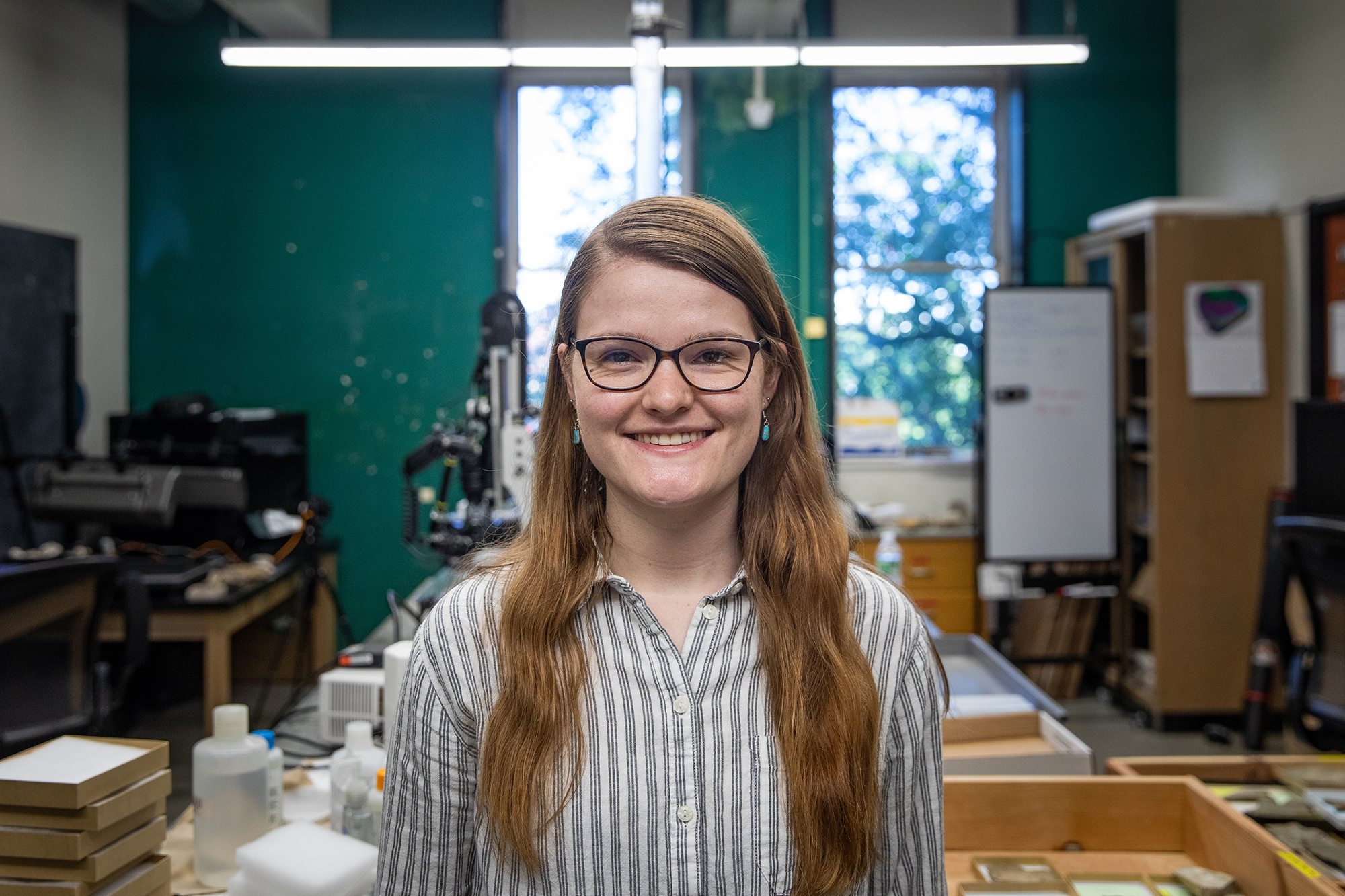

Utah native Mikaela Pulsipher came to the University of Missouri in 2018 for one reason: to work with Associate Professor Jim Schiffbauer.

“During my senior year of my undergraduate studies, I went to a national conference for the Geological Society of America (GSA) to network,” Pulsipher said. “I attended one of Jim’s presentations where he talked about his lab, the research instruments he has and the kind of work that he does. It was so fascinating — I wanted to know more about what he was working on and how I might be able to use the instruments.”

After the conference, the two were introduced by Schiffbauer’s former PhD advisor and they exchanged emails to talk about potential projects. After talking for a bit, Schiffbauer knew he had the perfect project for Pulsipher: the repository for quantitative analysis of the Steptoean Positive Isotopic Carbon Excursion (SPICEraq).

“As a researcher, you look for students whose motivation and drive are really clear — those who are really passionate about the questions,” Schiffbauer said. “I immediately knew Mikaela was one of them.”

The eagerness was mutual, but Pulsipher didn’t think it was the right time for her to start graduate school so she thought she would take a gap year. That plan changed in March.

“I got an email from Jim letting me know that he had a spot open up in his lab and that he wanted to know if I was interested in starting in the fall like I had originally planned,” Pulsipher said. “This time around, things felt different. I was in a better place to be making big decisions like this one and I agreed to at least come and visit Mizzou.”

Her trip to campus solidified her decision to become a Tiger.

“The visit, plus the fact that Jim reached out to me, specifically, to let me know he wanted me to work with him was a huge confidence boost that outweighed some of the lingering apprehension I had about grad school,” she said.

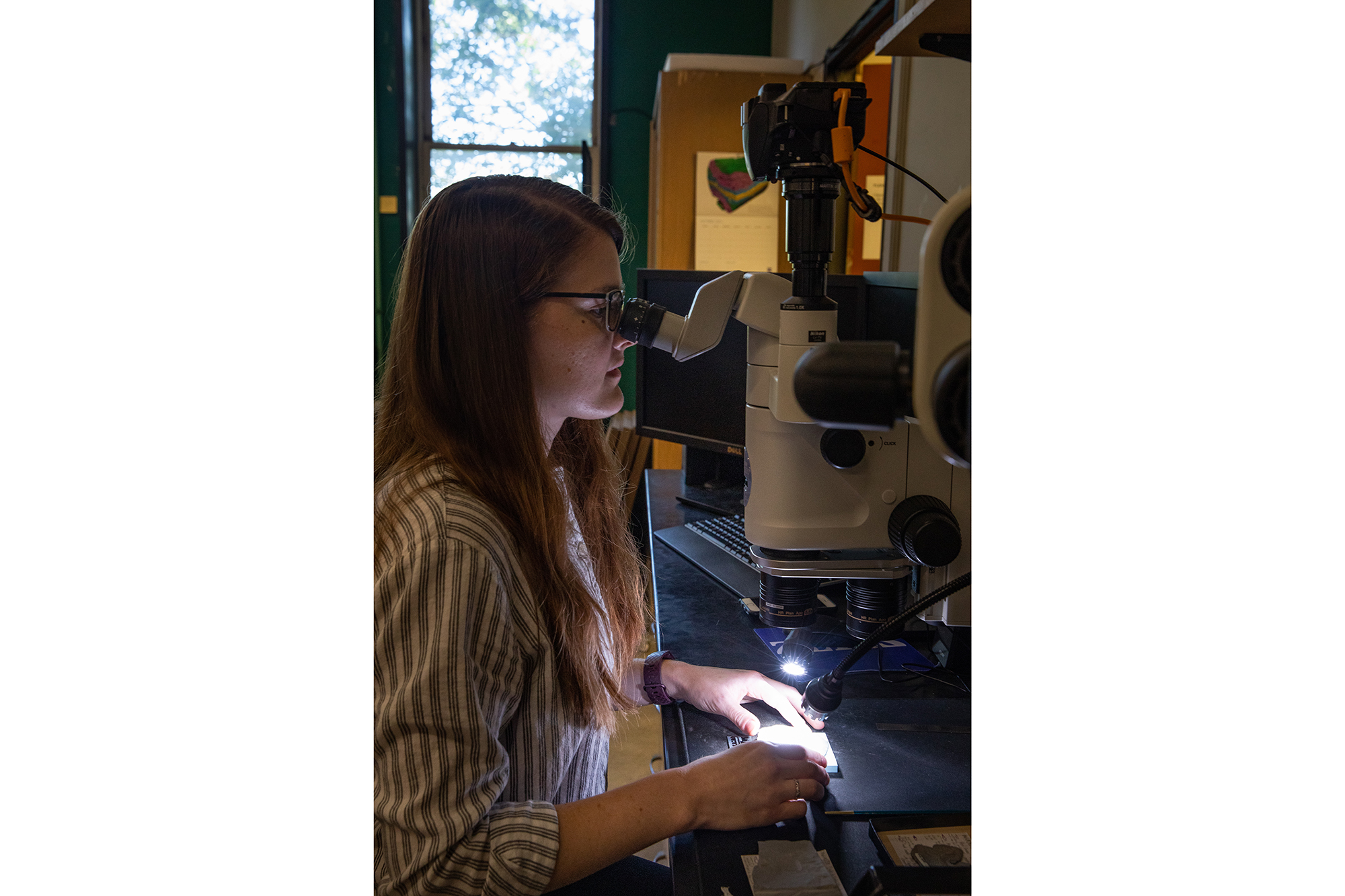

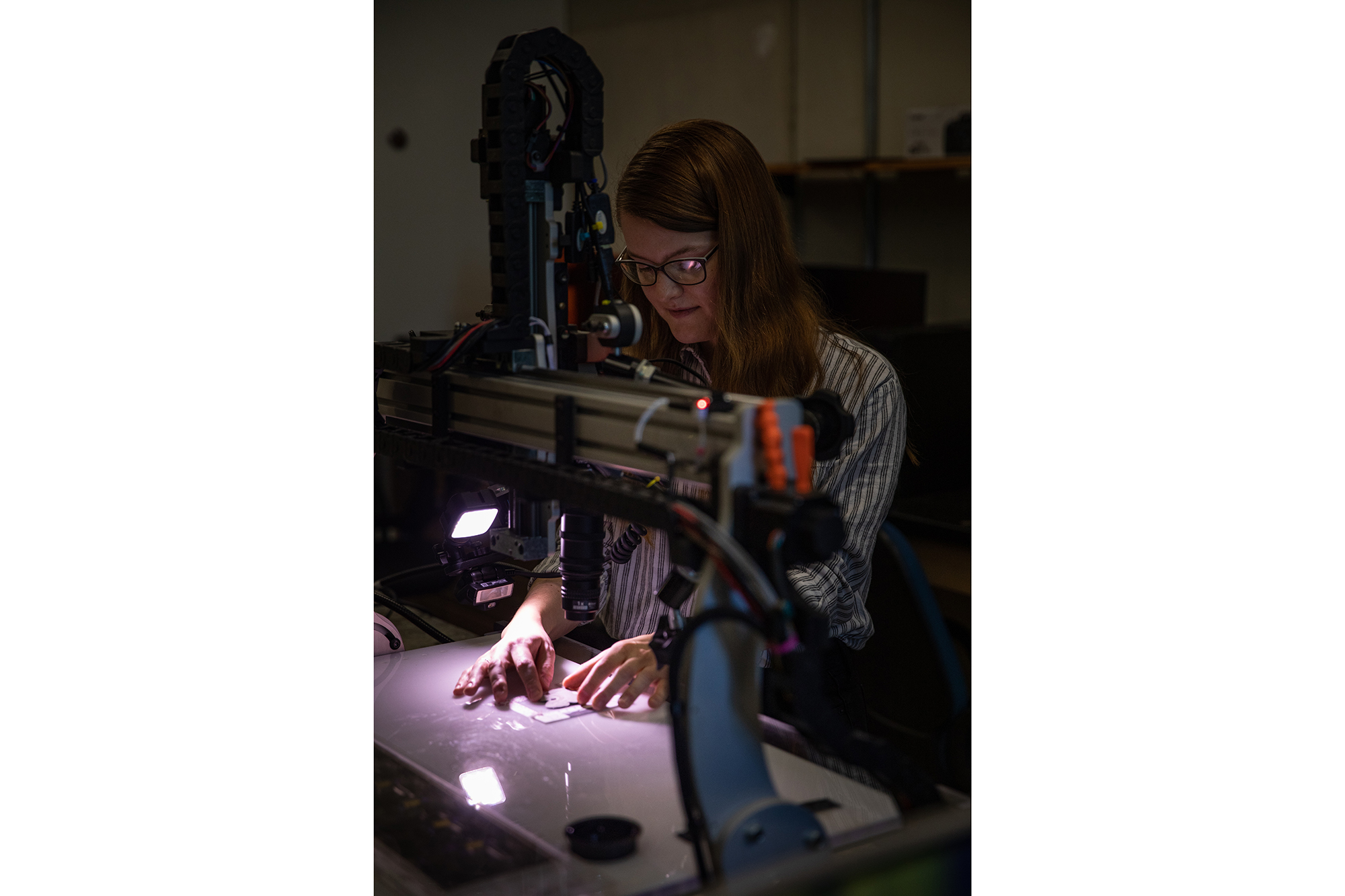

Getting to work

Once on campus, Pulsipher immediately started work on the SPICEraq project. The research looks at global data from 78 different sections of rocks and fossils from the Steptoean Positive Carbon Isotope Excursion (SPICE) event. This event occurred around 500 million years ago and has been documented in carbonate rocks around the world, including our own backyard here in Missouri. The SPICE records a significant fluctuation in carbon isotope values – which has been interpreted as an indication of changes in the chemistry of the global ocean. Like Pulsipher, researchers around the globe are interested the implications of the SPICE event, such as a possible decrease in oceanic oxygen content and a possibly related prehistoric extinction event.

While there are vast amounts of research done on each of the 78 SPICE sections, no one had compiled and analyzed the data to look at it from a global perspective – until now.

“We don't totally understand how this carbon isotope excursion happened, so the SPICEraq allowed us to evaluate, compare and contrast all of the different sections to help determine some of the potential causes of the SPICE event,” Pulsipher said.

As a result of her research, Pulsipher was recently awarded The American Geosciences Institute award — a recognition only given to two recipients this year in the U.S. She also won the Winifred Goldring Award from the Association of Women Geoscientists in 2019, an award that promotes the future of field mapping and data acquisition for the upcoming generation of women geoscientists.

“I think it's easy to get lost in the minutia of grad school and not pay attention to all of the the big jumps that you're making in your education and all of the hard work that you're doing,” Pulsipher said. “I'm really proud of myself for sticking through this really big project and having a published paper come out of it. I couldn’t have done that without the support that I’ve received from my peers and mentors in the Department of Geological Sciences here at Mizzou.”

Learning from the past

With the SPICEraq project concluded and the data made available to the public, Pulsipher and others on her team have shifted to a new project: describing and naming the fossils discovered by prominent female paleontologist Joanne Kluessendorf. Pulsipher said some of the fossils haven’t been given the proper attention since their discovery in the 1980s.

“It's really important to me, as a woman in paleontology, that we get to highlight some of the important work that Joanne did and to show that her work is still influencing women and science,” Pulsipher said.

Pulsipher not only sees the impact that women in paleontology have had in the past but plans to continue to make her own impact in the future — by helping undergraduate students at a crucial point in their lives.

“I want to be for someone else what my undergraduate professors were for me,” Pulsipher said.

Story written by Madalyn Murry