Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 17, 2021

Story by Justin Heckert, BJ ’02

Photos by Michael Cali, BJ ’17

The light gets weird in the Valley of Doom. It’s like the sunlight turns purple and eventually stains the eyes, and the student geologists are at the mercy of this phenomenon the longer they stay outside. They are in the middle of an epic and demanding hike this morning. It’s early May in central Wyoming, and they’ve been studying rock formations for hours. This is an oil field called Dallas Dome, with rusted pump jacks rocking back and forth in the warmth of the daylight. The light is a cloudless light and will temporarily burn the retinas of everyone working on a geologic map for this class; the professor tells her students this is called burn-eye syndrome, which isn’t nearly as horrible as it sounds. So, they will come back to their cabins at base camp later in the evening, when the air is cooler, weary from the day, with a kind of grape-tinted vision, all in the name of geology.

Sounds amplify and then disappear inside the Valley of Doom. The rustling pages of the students’ field guide booklets and their boots mashing the pebbles on the ground. They pass brambly wildflowers and shiny animal skulls in the empty brim of the valley. Their assignment this second week of camp sounds pretty simple: Study the rocks and create a geologic map from their interpretations of the land. But not being in the air-conditioning of a CoMo classroom, with a professor holding their hand, is much harder than it sounds. The assignment is just a part of the six weeks of Camp Branson, a required capstone class in the Mizzou geology program. The students have never actually done this, either — drawing a bird’s-eye view of rock formations while staring at them in person.

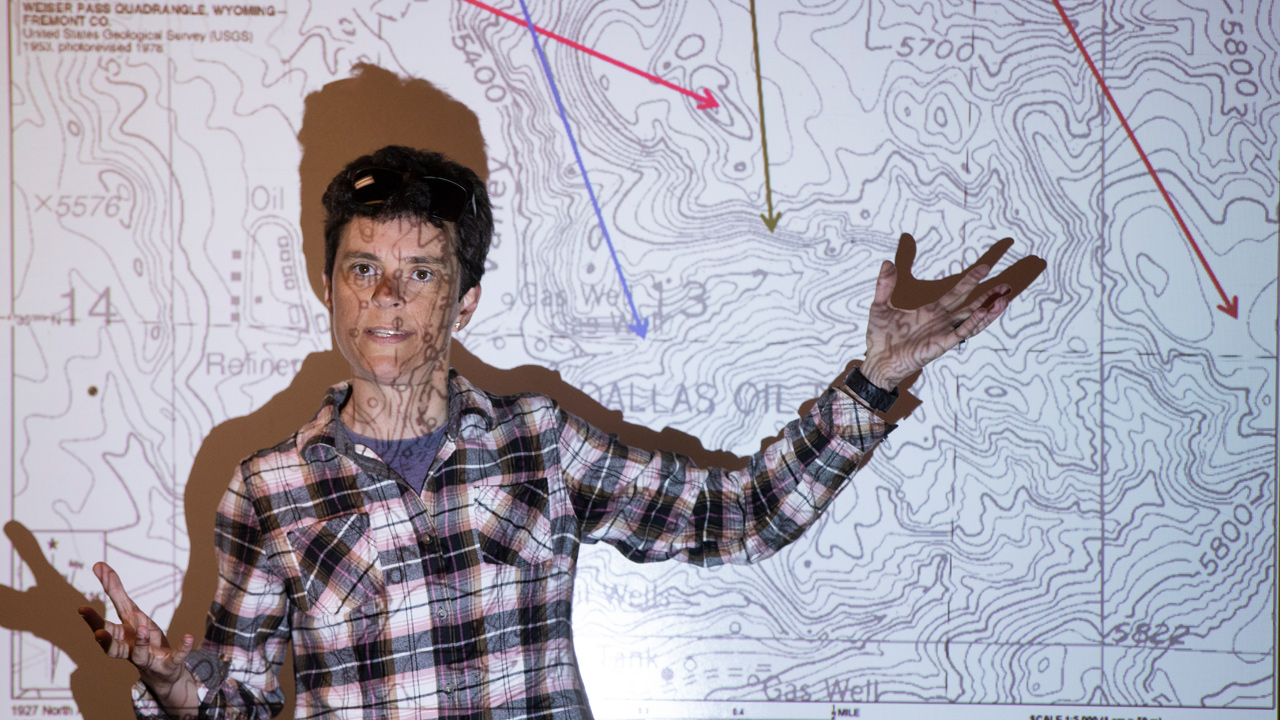

Miriam Barquero-Molina is the director of Camp Branson and a geology professor at Mizzou, and she told her class this morning — when everyone was groggily stepping out of the four white university vans that transported them from camp to the dome — “You know, beware of the hissing.” And again with a comedic chuckle: “Beware of the danger noodles. Danger noodles are everywhere. In the morning they tend to sun on the ridges. In the hot afternoon, they’ll rattle.”

“Don’t do a bad map or I’ll come to your wedding and find you!” she deadpans, and scattered laughter breaks some of the tension that this is an assignment for a grade. Miriam scans the valley with a hand shielding her eyes from the sun to make sure she can see all the students. In a couple days they will have to reconcile their interpretations and turn in a single field map agreed upon by the group.

“We don’t want this experience to be a pressure cooker,” Miriam says. “But we do want the students to know they can produce under stressful situations. People here discover their inner will.”

Heat comes right off the wild grass in the depths of the dome. The student geologists can see it radiate in waves off the ground as they continue up the cliff face like people who might later claim to have seen a ghost. Will Hunt labors with both the hiking and envisioning his assignment. The whole area where he’s been treading is red and white and brown with siltstone. Miriam has described this to him and the others as a wasteland. In its vast brightness, in the dryness it savages upon the lips and in the throat, the ground here manifests what geology majors might describe as geologic time, molded and shattered and then baked into hundreds of layers of variation in the same color. She expects Will and everyone else to tell the story of the earth by replicating the topography of this place onto a piece of paper, the map being an exercise of some ambiguity, tracing curved lines that represent the physical area as best they can, every line a different color. In 48 hours they will all be sitting in their groups in a cabin classroom fresh from three days of hiking without much time for arguing whose interpretations are the most precise. Former students have described the mapping experience as like trying to put together a big, subjective puzzle with only a few hours to do it. Will takes a blue pencil out of his backpack to continue tracing a line of juniper trees or white layers of Alcova limestone or grain-dominated packstone on the map he’s carrying, folded, in his hands. “Look at the students, contemplating their life choices!” Miriam wisecracks. Because of the quietude, because of the view, this class begs for students like Will to stare around and ponder rocks being billions of years old.

Is that an eagle? someone ahead of him asks, as the student geologists are pretty much always looking up when there’s a bird noise. Will can’t really hear the bird noises, or the hissing, for that matter. He cannot hear at all in his left ear. He has only 30% hearing in his right. One of the teaching assistants follows behind in case she needs to warn him about danger noodles.

This really doesn’t feel like a class at all, hiking the Dallas Dome into the valley and then up to its highest point, which Miriam calls Football Hill, 6,000 feet above sea level; that is, meandering the trails and ridges for about 7 miles and standing on the edge of all these little cliffs that feel like they’re almost touching the clouds and having a clear view of the infinitum of the Western horizon in the gleaming and purpling distance. No, this feels more like a pilgrimage, like some kind of tour — the 14 students and three teaching assistants following behind Miriam, pausing as she stops at what she calls geologic markers along the trail, to explain, sometimes humorously, what it is that they see. “In the classroom, you can’t get this. Your lives change when you experience this, y’all,” she says, using her hands in front of her face to frame a rock formation of Alcova limestone to see if she can get across to them how she sees it, telling them this is how she visualizes 3D structural geology. She affirms to them: “This is rock science, not rocket science!”

Students standing behind Miriam and gazing through this makeshift frame of her fingers are reminded by a TA that a geologic map is just superimposing exposed rocks on the surface of the earth, a way of studying how they behave, erode or deform, a mode of analysis with applications like drilling for oil or monitoring changes in the cliffs. Will is near the back of the students in single file, watching the person in front find the best footing for a better way up the slope, lugging his backpack through the branches on the side of a rock formation, trying not to slip. His backpack is padded with colored pencils for the map, a Brunton compass that every student carries and that Miriam has to teach them how to use, a rain jacket, water, and one of those hardbound field guides where students take notes and identify rocks. It’s the second week of camp, the first day of long hiking — not all students are great at walking in elevated and rugged conditions, it turns out — and for someone who grew up on a farm outside Huntsdale, Missouri, the trail is slippery and unforgiving.

At 26, Will is one of the oldest students at Camp Branson, originally going to Mizzou a few years ago and then getting dismissed for grades. So, he went to Moberly Area Community College for two years and became a better student, he says, and there found an interest in geology. “I like the thought of geology,” he says. “I like being outside. It involves everything — history, math, chemistry. I find that appealing. Telling the story side of the land. Going out here and figuring out what happened.”

Will is a big guy, in a heather-gray T-shirt, angular sunglasses, this unruly beard that fits perfectly with the landscape. Back home, he likes to go fishing with his twin brother on the Missouri River. He has a tattoo on his left arm of a trotline in the water. At the entrance to Football Hill, the students have to hoist themselves up over the final ridge, Will on his stomach, then standing up and patting the dirt off the knees of his jeans. He sits in the shade of a juniper tree, catching his breath. Across from him, a group of students plays baseball using a twig as a bat and pinecone as a ball.

“I have been looking forward to this camp,” he says, taking a drink of water. “This is the furthest west I’ve been in the U.S. Without cell reception, you have to go back to doing things you did when you were younger. We play Uno and chess in the evenings. I brought some books. I brought some fishing gear and want to try to catch some trout in the river.”

Pretty much everyone calls Camp Branson The Island. The TAs, the students and Miriam herself, with affection. Even this older guy nicknamed Hotrod, the beloved caretaker of the grounds, who walks around smoking a stogie and holding a piece of gravel in front of his face winking to Miriam like, “You know, they’re just rocks.” The base for Camp Branson is cradled by two arms of the Popo Agie River and just across from these looming and impenetrable bluffs that seem to first change color and then disappear in the night. One thinks of an island and can hear water in the imagination and can feel the enhancement of being able to get a hit of the natural air. And the students really do wake up in their cabin bunks to draw mountain breaths with the river softly singing to them.

Pretty much everyone calls Camp Branson The Island. The TAs, the students and Miriam herself, with affection. Even this older guy nicknamed Hotrod, the beloved caretaker of the grounds, who walks around smoking a stogie and holding a piece of gravel in front of his face winking to Miriam like, “You know, they’re just rocks.” The base for Camp Branson is cradled by two arms of the Popo Agie River and just across from these looming and impenetrable bluffs that seem to first change color and then disappear in the night. One thinks of an island and can hear water in the imagination and can feel the enhancement of being able to get a hit of the natural air. And the students really do wake up in their cabin bunks to draw mountain breaths with the river softly singing to them.

On the second day of the mapping assignment, the student geologists take their seats in the classroom cabin at wooden tables by a chalkboard in the front of the room, three to a group, personal maps unfurled between their elbows — all these first attempts to whittle the Dallas Dome into hundreds of colorful lines. Miriam is walking around, an eyebrow akimbo, checking on their progress, along with the three TAs, each of them trying to mollify the time crunch of the assignment after breakfast and psych them up for another day of hiking and to help as best they can without giving anything away. The open session will be replaced in a day by the urgency of the students trying to come to a consensus within their groups at the end of the assignment. And at the end of three weeks here, they have to take an exam where they draw their own map solo.

Former campers recall not just the demands of the map assignment but the field camp itself and all that it asks as maybe be the hardest class they’ve ever taken. The heat. The hours. The mornings coming early over the ridge of the cliffs. With a caveat that after the whole experience has a chance to sink in, strangely, it turns out to have been a really fun class, too.

When they arrive from Columbia, at first it can seem to some of the students like a strange roadblock to graduation, an inconvenience to try and find a way to pay about $2,500 in camp fees and then come halfway across the country to boot.

In a regular year, a non-COVID year, these 14 students would number more like 40, some from universities all over the country instead of just Mizzou. They would get to go into that weird and beautiful little town of Lander just a few miles away to check their cell phones and blow off steam, something this year’s students can’t do because they can’t leave The Island, where there’s no reception. Yes, this is a special year at Camp Branson, unlike any in the previous 110, owing to the demands of COVID. This has meant some cabin fever, of course, and that the student geologists at Camp Branson in 2021 spend their time reading paperback fiction and playing cards in the firefly light of the evening, sitting beneath the aspen trees and studying. Or learning the banjo.

Miriam is standing away from the student geologists on the third day of the assignment. The students on their own in the valley, sequestered into their mapping groups, sometimes quibbling about where to go and where the lines should sit on the map and who should be the leader. She is standing back on the trail, watching them disperse, knowing that this camp will “separate the geologists from the non-geologists,” like one of her TAs said, even if it’s technically everyone’s major.

Miriam is standing away from the student geologists on the third day of the assignment. The students on their own in the valley, sequestered into their mapping groups, sometimes quibbling about where to go and where the lines should sit on the map and who should be the leader. She is standing back on the trail, watching them disperse, knowing that this camp will “separate the geologists from the non-geologists,” like one of her TAs said, even if it’s technically everyone’s major.

Miriam is 42 and athletically trim and gets up before dawn. Before most anyone else opens their eyes at Camp Branson, she might’ve taken her mountain bike and pedaled around the cliffsides or down to Lander, many miles in the early cold. Then after breakfast, she gives a lecture. Then leads the students out into the wild, poking her walking stick into the ground like she wants the Valley of Doom to know that she’s returned. “I pour my heart and soul into this camp,” she says. “When I leave, I miss my mountains. My scenery.”

She grew up in Spain, in Asturias. That is where she hiked with her family and became fascinated by rocks. She came to the U.S. for graduate school at Wisconsin and then UT Austin and in 2009 was hired at Mizzou, where she wanted to work because her dream was to run a field camp. Her family back home still thinks she teaches Spanish. “No!” she always tells them. “I’m a geologist. We interpret the landscape. We are the people who understand the earth.”

A couple years ago on the Fourth of July, a former Camp Branson student went back on a trip out west from Missouri and “got the same kind of sensation like when you return home somewhere,” he says. Clark Thomas is 27 and took Miriam’s class as a junior. “Lander is not my home,” he says, “but I felt like … I was entering my territory.” Of course, Clark spent six weeks in Wyoming in 2015, and one of his assignments was making a geologic map. On returning from the seclusion of the camp he experienced a kind of reverse culture shock. He woke up the first morning and his roommates told him, “We need to throw you into the shower and take you to a Chipotle,” he says.

A couple years ago on the Fourth of July, a former Camp Branson student went back on a trip out west from Missouri and “got the same kind of sensation like when you return home somewhere,” he says. Clark Thomas is 27 and took Miriam’s class as a junior. “Lander is not my home,” he says, “but I felt like … I was entering my territory.” Of course, Clark spent six weeks in Wyoming in 2015, and one of his assignments was making a geologic map. On returning from the seclusion of the camp he experienced a kind of reverse culture shock. He woke up the first morning and his roommates told him, “We need to throw you into the shower and take you to a Chipotle,” he says.

As he walked around Columbia for a few days reacclimating to civilization, in this post-camp daze, it began to sink in, even then, something that he would realize all these years later, at law school at Ole Miss: He’d had a kind of revelation at camp that unfurled itself into him, that has been there since. “What does camp mean? Well, it developed this … like, desire to explore.” As a senior, he took another class with Miriam about the formation of the Iberian Peninsula that sent him to Spain. “After Camp Branson, I couldn’t satiate this desire to go out and get different experiences. That field camp, the nature of it, cultivated within me through her guidance — that’s what drove me to move to China for a year after I graduated. I don’t know if I would have considered moving internationally if I didn’t have that experience at field camp. And gotten that taste. Surviving that class … has stuck with me.”

At the end of his own geologic mapping assignment, there was a reckoning: “Once you come back from the field, it is really tense,” he says. “You don’t have a ton of time, and everyone has a different opinion. We’re all here in beautiful nature as friends, but then you flip this switch and have to advocate for your opinion; you have to reconcile each other’s differences in putting out a product.”

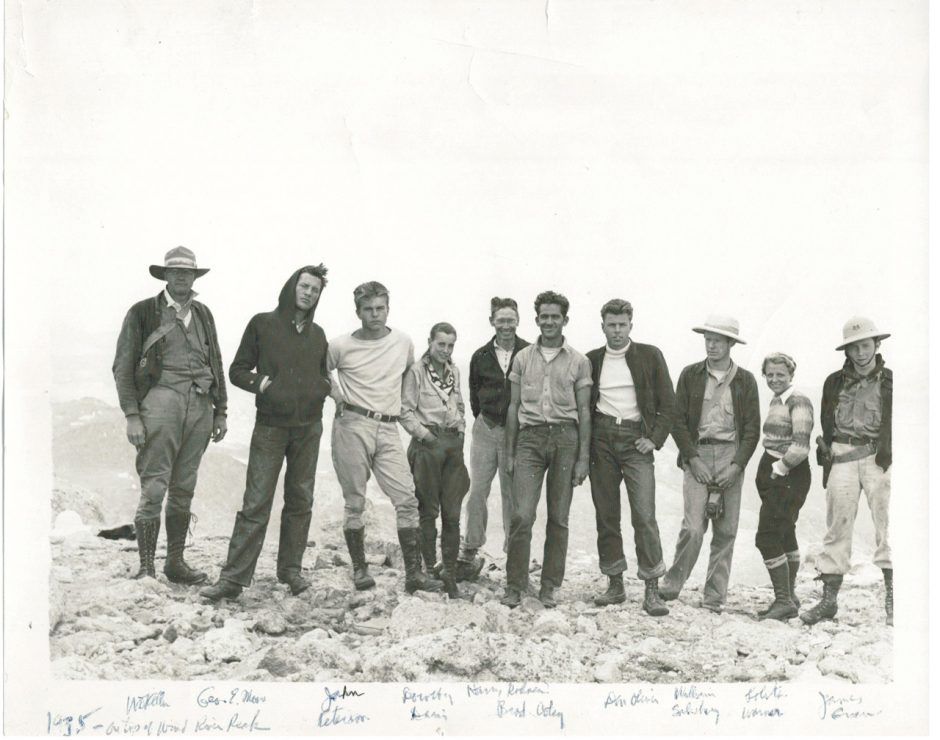

This year the student geologists were privy to take a picture at the camp together, which is kind of a rite of passage before they leave. Like having a bonfire, or cooking s’mores, or one of the nights when they all dress up for a theme in the chow hall. This happens every year at Camp Branson, little acts of commemoration, like jumping into the lip of the very cold river that everyone for some reason calls the Hot Tub. This year, a group of students designed camp T-shirts.

This year the student geologists were privy to take a picture at the camp together, which is kind of a rite of passage before they leave. Like having a bonfire, or cooking s’mores, or one of the nights when they all dress up for a theme in the chow hall. This happens every year at Camp Branson, little acts of commemoration, like jumping into the lip of the very cold river that everyone for some reason calls the Hot Tub. This year, a group of students designed camp T-shirts.

It was a weird year for Miriam — what she calls the COVID year, a cabin-fever year that left a bittersweet stain out of all the other years, Miriam always being kind of mentally exhausted at the end of the six weeks and driving back home in the geology department pickup truck, that maudlin journey back to university life. “I’m strung out, man,” she says in October. “It’s draining. It’s a lot of people-ing, especially when no one really got a break from being around each other in the summer of 2021.”

When Will gets back home, he is accepted into grad school at Mizzou and becomes a teaching assistant in the very department that sent him to Wyoming and where he basically had to learn how to hike. He quits the hospital job that had him working night shifts before he went to camp, the one where he earned the money to go.

After acclimating to hiking and knocking out the map assignment, he says, “We did some subsurface geology, looking for aquifers. We put geophones in the ground and made the ground vibrate, studying seismology. Basically, the first part of camp was above ground, and the second part of camp was what was underground, what we couldn’t see. It all reinforced wanting to work out in the field. For me, wanting to be a field geologist.” Before posing for the group picture, some of the students in this year’s class had seen these relic photos of campers dating back to the early 1900s. It was hard not to find some kind of connection to those pictures, even the ones from 1911, the first students at camp, ancient Mizzou undergrads wearing high boots and playing old-timey games like horseshoes. The camp left its impressions beyond the grades students got from their funny yet earnest first attempts at geologic mapping, beyond the lectures, the hiking and the hot showers. Geology is pretty much the study of time, like Miriam told the students; geology is the study of the landscape as a result of geologic time. To be a geologist, you have to appreciate the idea of big time, Miriam says, almost unfathomable time, kind of what it’s like to look at a brittle old picture taken in the same valley on the same island in the same camp with people who lived back home in Missouri 110 years ago, and then wait for your own memories to be weathered into shape.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.