July 26, 2021

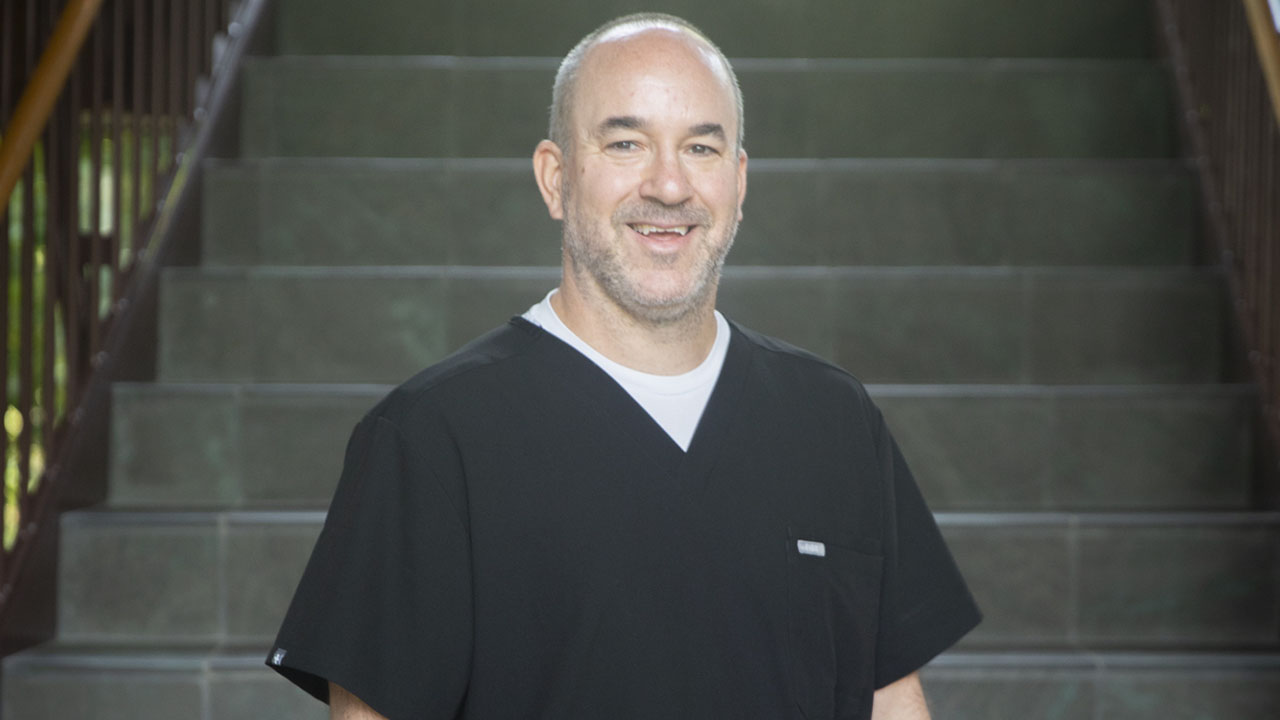

For almost two decades, Craig Emter, an associate professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Missouri, has been researching how to use exercise to treat heart failure.

Not long ago, Emter’s expertise became personal: He began having chest pains while exercising. Turns out he had a blockage, which might have gone undetected if not for his commitment to exercise. Thanks to the installation of a stent in his heart, Emter is back at work, more committed than ever to his research.

“It’s deeply personal and a huge reminder of how important the work in my lab is to not only myself and my family – who have a profound sense of relief – but also the millions of individuals living with cardiovascular diseases,” he said. “I consider myself extremely grateful that I have the training and experience to realize what was happening to me and acted before something happened that would have left permanent damage to my heart.”

Emter is among 15 researchers and their teams preparing to move their work to the new Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building at Virginia Avenue and Hospital Drive. He is looking forward to having his whole team under one roof and being surrounded by opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration.

“We are looking at very targeted, very specific ways to treat heart failure,” Emter said. “This is an awesome opportunity for us.”

NextGen Precision Health is the highest priority of MU and its partners across the UM System, MU Health Care and MU Extension with the goal of developing innovative solutions for society’s greatest health challenges. The four-story building, scheduled to open in October 2021, brings together an unparalleled set of resources with the ultimate objective of shortening the nearly two-decade journey it takes for research findings to reach clinical practice.

Among Emter’s findings is the discovery that exercise can improve the health of blood vessels in the failing heart. He found that regardless of exercise intensity or duration, any level of exercise resulted in improved health of blood vessels in the heart.

Emter grew up in Wyoming, where, until he was 8, his family lived in the country miles from the nearest town. He remembers driving for what felt like a long time over dirt roads just to catch the school bus.

“Then it was another 35 to 45 minutes to reach the school,” he said.

Though his parents didn’t farm, his grandparents did, and Emter grew up around horses, cows and other livestock. By high school, his family had settled in Riverton, Wyoming, a small town known as a gateway to Yellowstone where Emter played numerous sports offered at the school and graduated valedictorian of his class. His favorite subjects were math and science. He enrolled at the University of Wyoming with dreams of becoming a physical therapist. But after a summer internship at a local hospital in Laramie, Emter knew physical therapy wasn’t for him. However, the next summer he interned with a researcher studying cardiovascular physiology at the university, and Emter was sold — he wanted to study the heart.

After receiving a master’s in exercise physiology from Boise State University, Emter earned a doctorate in integrative physiology at the University of Colorado. It was during his doctoral work that Emter began to merge his love for cardiovascular research with exercise physiology.

Emter came to MU in 2006 for the opportunity to continue his work in cardiovascular research using swine models.

Surprisingly, pigs and people have similar blood vessels and heart muscles, and MU is renowned for its expertise in large animal models. Emter and his research team are working with the models to determine how much and what kind of exercise is appropriate for heart failure.

“We want to get to the point where we can prescribe exercise like we do drugs for people with heart failure,” he said.

Emter plans to take advantage of every opportunity offered to him and his research team at NextGen.

“I’d like to think we can utilize this opportunity to make a discovery with lasting impact for treating heart failure,” he said.