Feb. 24, 2021

Contact: Austin Fitzgerald, 573-882-6217, fitzgeraldac@missouri.edu

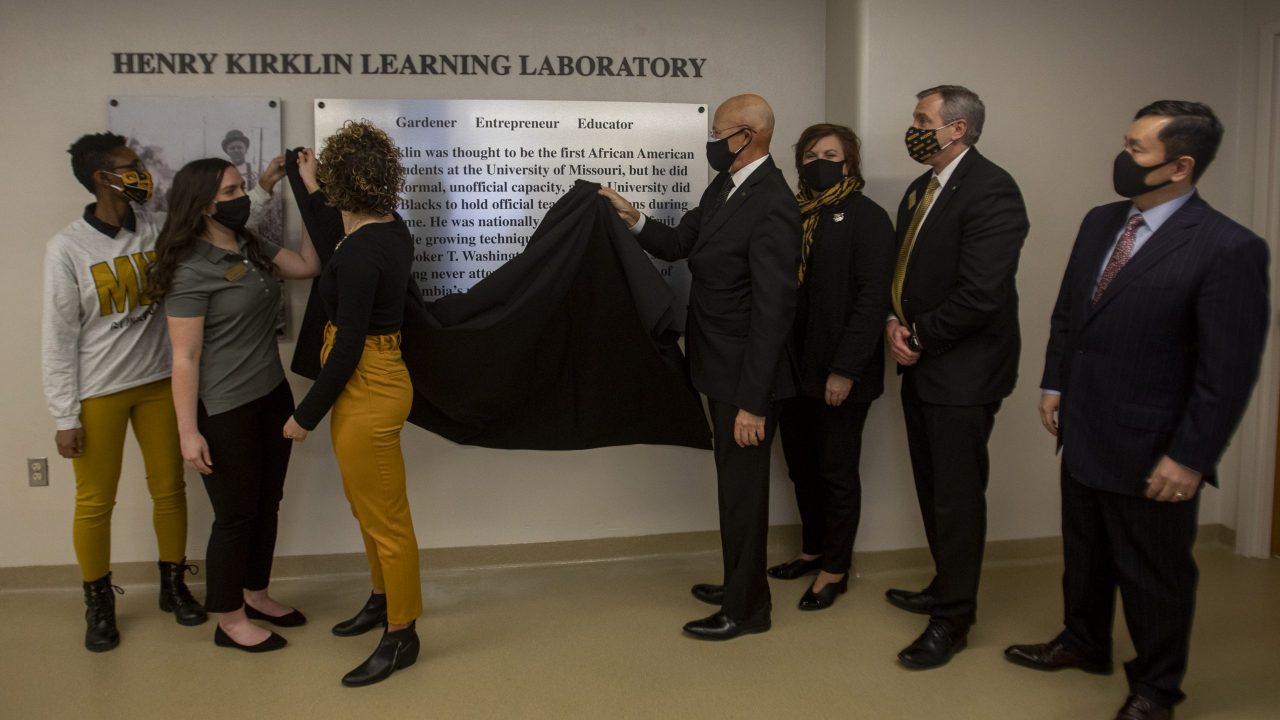

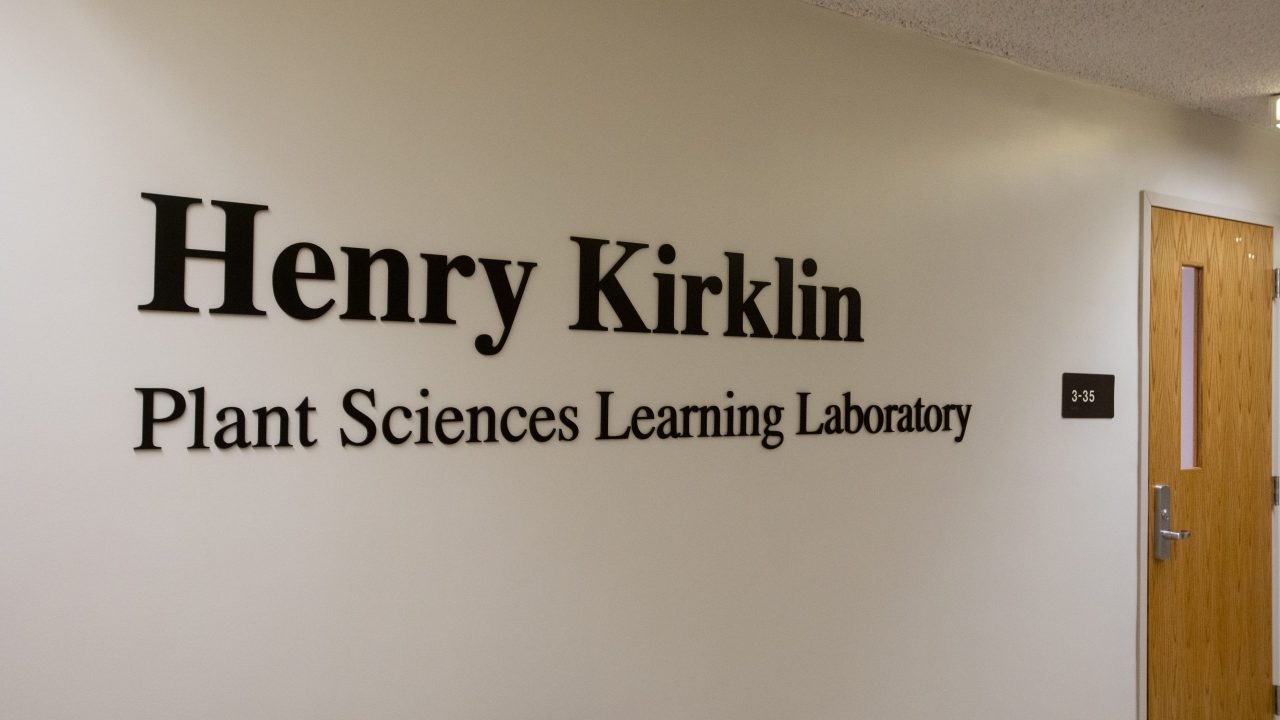

The University of Missouri today honored Henry Kirklin, a celebrated Black farmer and educator who lived in and around Columbia from 1858 until his death in 1938, with the naming of the Henry Kirklin Plant Sciences Learning Laboratory in his honor. Nearly a dozen of Kirklin’s descendants were in virtual attendance as leadership of MU and the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources (CAFNR) dedicated the lab, which recognizes the man believed to have been the first Black teacher at the University of Missouri.

“Henry Kirklin’s vision for education was comprehensive,” said Mun Choi, president of the University of Missouri. “He believed not only in the immediate value of learning, but also in its generational value. We see that in the legacy he left for Mizzou.”

During Kirklin’s lifetime, the university prevented Black people from holding official teaching positions. Kirklin taught in an unofficial capacity in the horticulture department, where he educated students on how to prune and graft plants. Nearly a century after his death, Kirklin’s great-great granddaughter was gratified to see her ancestor honored for his accomplishments.

“It’s fantastic to see this recognition of what he meant to the Columbia community and to the university,” said Leah El-Amin, a direct descendant of Kirklin through her mother, Aaron Coulter. “He was a successful businessman and educator at the turn of the century, which was significant and groundbreaking for that time. It is exciting to know that his legacy is carrying on with this lab.”

The lab features a series of digital displays that can be connected to microscopes to display detailed images of plant cells to the entire class, part of a suite of state-of-the-art technology that allows plant sciences students to perform a variety of hands-on tasks without leaving the lab. Christopher Daubert, vice chancellor and dean of CAFNR, extolled these features in his remarks Wednesday.

“The overall design and technology of the new Learning Lab will enable our college to better prepare students for the modern plant science work force, and it will be a centerpiece of undergraduate recruitment,” Daubert said. “Technology in the classroom will enable virtual lectures from experts outside MU or virtual field trips to world-class facilities like the Danforth Plant Science Center in St. Louis.”

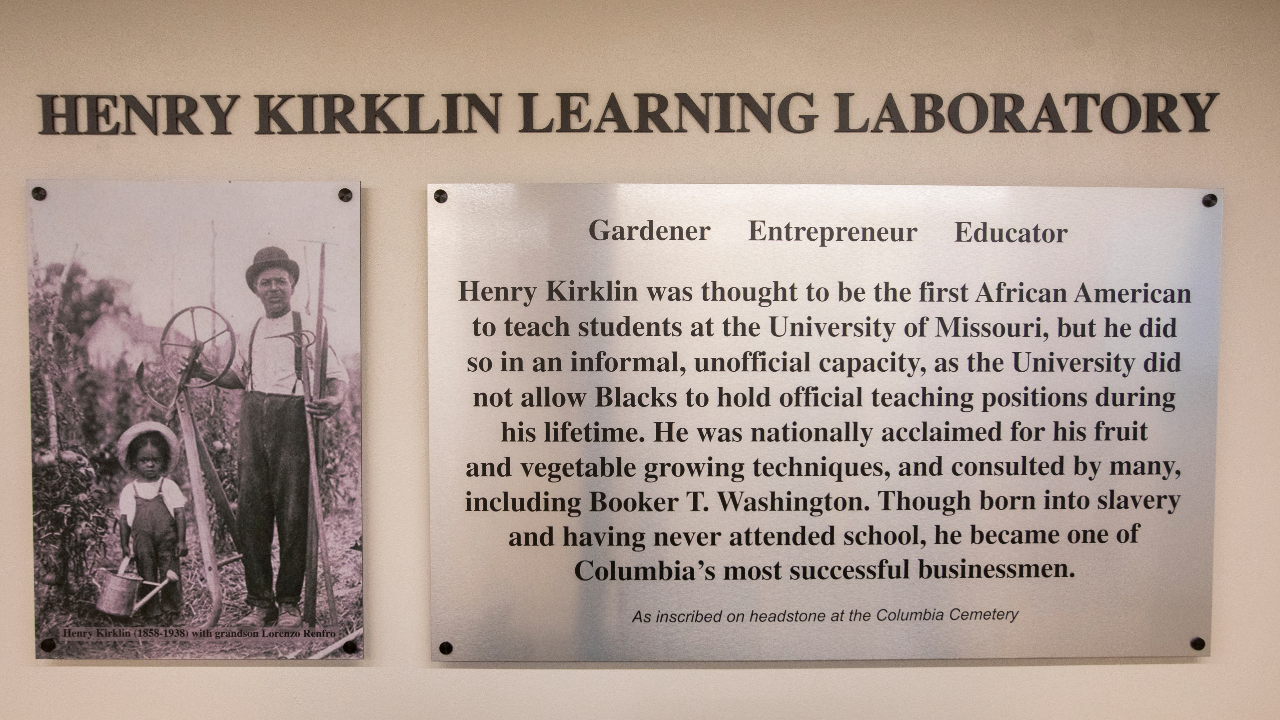

A brief history

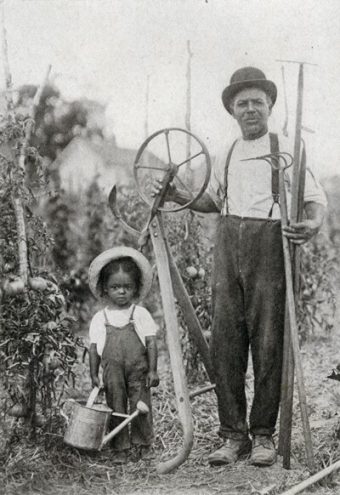

Kirklin was born into slavery in 1858 on a farm east of Columbia and was freed by the age of 5. According to the State Historical Society of Missouri, Joseph Douglass, a local greenhouse and nursery owner with ties to MU, hired a teenaged Kirklin to work at his business, a job that eventually turned into a position at MU’s horticulture department as a greenhouse supervisor and gardener. Kirklin’s skills at managing plants were striking, and he was quickly given the role of teaching students practical gardening skills. But despite his obvious talent, he was forbidden from teaching inside in a classroom and was never given an official faculty position.

After his time at MU, Kirklin started a farm in Columbia. Predictably, it became successful almost immediately. He soon acquired multiple properties, and horticulture students now came to his farms to see him in action. He was particularly skilled at cultivating strawberries, and his fruits and vegetables were renowned for the quality and high yields he was able to produce. In the Columbia community, he was known to mentor and financially assist young Black students who wanted to go to Lincoln University, the only local university open to Black students at the time.

“There is evidence that Kirklin was providing produce to all the major grocery stores in town, and to the university dining halls, including the University of Missouri,” said Chris Campbell, the executive director of the Boone County History & Culture Center. “When he wasn’t attending national conferences and meeting the likes of Booker T. Washington, he spent his whole life in Columbia. He had relationships everywhere.”

While many people are aware of John William “Blind” Boone, another early Black resident of Boone County who became a nationally recognized musician and composer, Kirklin is comparatively little-known, according to Billy Polansky, the executive director of the Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture (CCUA). For someone so well-known in his day — a local newspaper stated in 1903, “No man in Columbia stands higher in the estimation of the people than does Mr. Henry Kirklin,” and noted that he would have an exhibit at the upcoming St. Louis World's Fair — the lack of awareness surrounding Kirklin’s role in Columbia’s history doesn’t sit right with Polansky.

“More and more people want to know about the contributions of Black historical figures, and at the same time, they want to know more about their food and where it comes from,” Polansky said. “In Henry Kirklin, those movements converge. He was educating young people about farming and advocating for urban agriculture long before the CCUA. He truly was one of Columbia’s founding fathers, and his name deserves more recognition.”

Resurrecting a local icon

The road to the newly renovated lab’s dedication began with “History Comes Alive,” an annual event in which local actors portray famous figures buried in the historic Columbia Cemetery. In May 2019, CAFNR’s senior associate dean and director of academic programs, Bryan Garton, attended the event and happened to witness actor Rodney Sheley’s portrayal of Kirklin.

The performance was scripted by Campbell, who wanted his script to do more than educate his audience; he wanted to call them to action. Toward the end of Sheley’s performance, the actor told the audience — in character as Kirklin — that though he had been buried in the Columbia Cemetery, he still didn’t have a headstone more than 80 years later. The crowd got the message.

“When the performance ended, people were already trying to donate money toward a headstone,” said Garton, who is also a professor of agricultural education and leadership. “The folks at the cemetery had to turn them away at first, because there was no way to accept their donations at the time. With Chris Campbell and the Friends of the Historic Columbia Cemetery, we formed a committee, and before long, Kirklin had a beautiful headstone.”

The grave marker, officially unveiled last November after a delay due to COVID-19, is adorned with engravings of tomato plants, a nod to Kirklin’s prize-winning skill at breeding fruits and vegetables. Along with the Henry Kirklin Community Garden, a 25,000 square foot botanical homage to Kirklin planted a year before near the MKT Trail, the headstone generated a buzz in the community that Kirklin’s name had not seen in nearly a century.

But Garton wasn’t satisfied. He knew a lab was being renovated in MU’s Agriculture Building with state-of-the-art equipment for plant sciences students to learn practical horticulture skills — the kinds of skills Kirklin once taught his students. He sensed an opportunity.

“I made it known that I thought we should name this new lab after Kirklin, because the direct, hands-on learning that will take place there is exactly how Kirklin’s students learned in his day,” Garton said. “The idea was to keep Kirklin’s spirit alive.”

The idea had plenty of momentum. A community garden had been planted in Kirklin’s name. A long-overdue headstone had been erected. This was another logical step.

Now that the lab has finally been dedicated, the last thing anyone involved wants to do is let Kirklin fall back into obscurity.

“Many Black Columbians of years past have yet to be fully recognized for their achievements,” said Campbell. “We need to be reminded that while Columbia was not particularly good at recognizing its early Black achievers, it’s not too late to do it now. We need to keep unearthing and celebrating that history.”

With that in mind, during a planning meeting for the lab dedication, Campbell suggested to Garton the possibility of a scholarship for minority students in Kirklin’s name. Garton loved the idea, and the Henry Kirklin Memorial Scholarship for underrepresented minority students was announced Wednesday during the ceremony.

For Polansky’s part, he is working with local author Charlis Phillips on a children’s book celebrating Kirklin’s life and legacy, and he hopes the increased awareness of Kirklin’s accomplishments could translate to positive changes in the community.

“There is not a single black farmer in Boone County as of the last USDA census,” Polansky said. “That’s incredible when you consider what Kirklin was doing a hundred years ago. When kids start seeing farmers that look like them, there will be more Black farmers, and every effort to raise awareness of Columbia’s Black forefathers and early Black farmers is a step in the right direction.”

As for Kirklin’s greatest legacy of all — his descendants — they are keeping his spirit alive in their own way.

“I know our great-great-grandfather would be proud,” the family said in a statement read by Choi during the ceremony. “Most, if not all, of his descendants are college-educated.”