Published on Show Me Mizzou Jan. 15, 2021

Story by Carson Vaughan

Beth Peterson was supposed to be a wilderness guide. That was the plan, anyway, insofar as a high school senior can conceive of the future. She would spend her life outdoors, hiking and climbing and unlocking the natural world for scores of curious campers. But the path quickly forked: The University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire didn’t offer much in the way outdoor leadership, so she studied advertising instead. And when she tried again at Wheaton College, pursuing her master’s in 2004, the program folded.

For a moment, the path seemed to vanish altogether, overgrown with the brambles of academia. But on a lark, she enrolled in a creative writing course. She read Baldwin. Montaigne. Didion — she loved Joan Didion. She feasted on the essay — the form itself — with a hunger previously unknown. Perhaps, she began to realize, she hadn’t wandered so far after all. “The idea of being able to write your life, write your experiences, write other people’s experiences, do research, get out — I just found that so compelling,” says Peterson, PhD ’14.

At the same time, she’d fallen in love with Norway. She’d already spent a few summers in her ancestral homeland, climbing and guiding and forgetting — for just a few months — the “uncertain attempts at navigating a career and life and relationships,” she would later write. And in that period, hardly a blink of an eye in glacial time, she’d witnessed a new lake melt from Jostedalsbreen, the largest glacier in continental Europe. She wasn’t naïve; she wasn’t blind to a warming planet. But suddenly, climate change was knocking on the door, a direct threat to a landscape she’d grown to love.

“When I saw the glacier, it was just huge, and I thought, ‘This is a landscape that needs to be preserved. It’s important. It’s beautiful.’ ”

And now, reading this genre her teacher called “creative nonfiction,” she began to sense the possibilities. She began to understand the essay as a venue for curiosity, for an adventure in form and function, for confronting this glacial lake, expanding every year, and how small — how powerless — she felt in the face of a warming planet. A way to shepherd the skeptical into new territory.

“There’s only so much I can do,” she says. “But I felt like writing — this makes sense for me because if people could connect with the landscape, if they can connect with me, if they can connect with the narrative, perhaps they’ll start to believe or think about these huge environmental issues in new ways.”

Already equipped with multiple degrees, she experimented briefly with careers in teaching and publishing before enrolling in the Master of Fine Arts program at the University of Wyoming in 2007 to study creative nonfiction. It was there, in Laramie, that Peterson truly began to wrestle with the craft. She read her first braided essay, Maureen Stanton’s “Laundry,” marveled at how the different narrative threads built upon and spoke to one another. She wondered if the form might work for a story of her own, a story still percolating from her time in Norway.

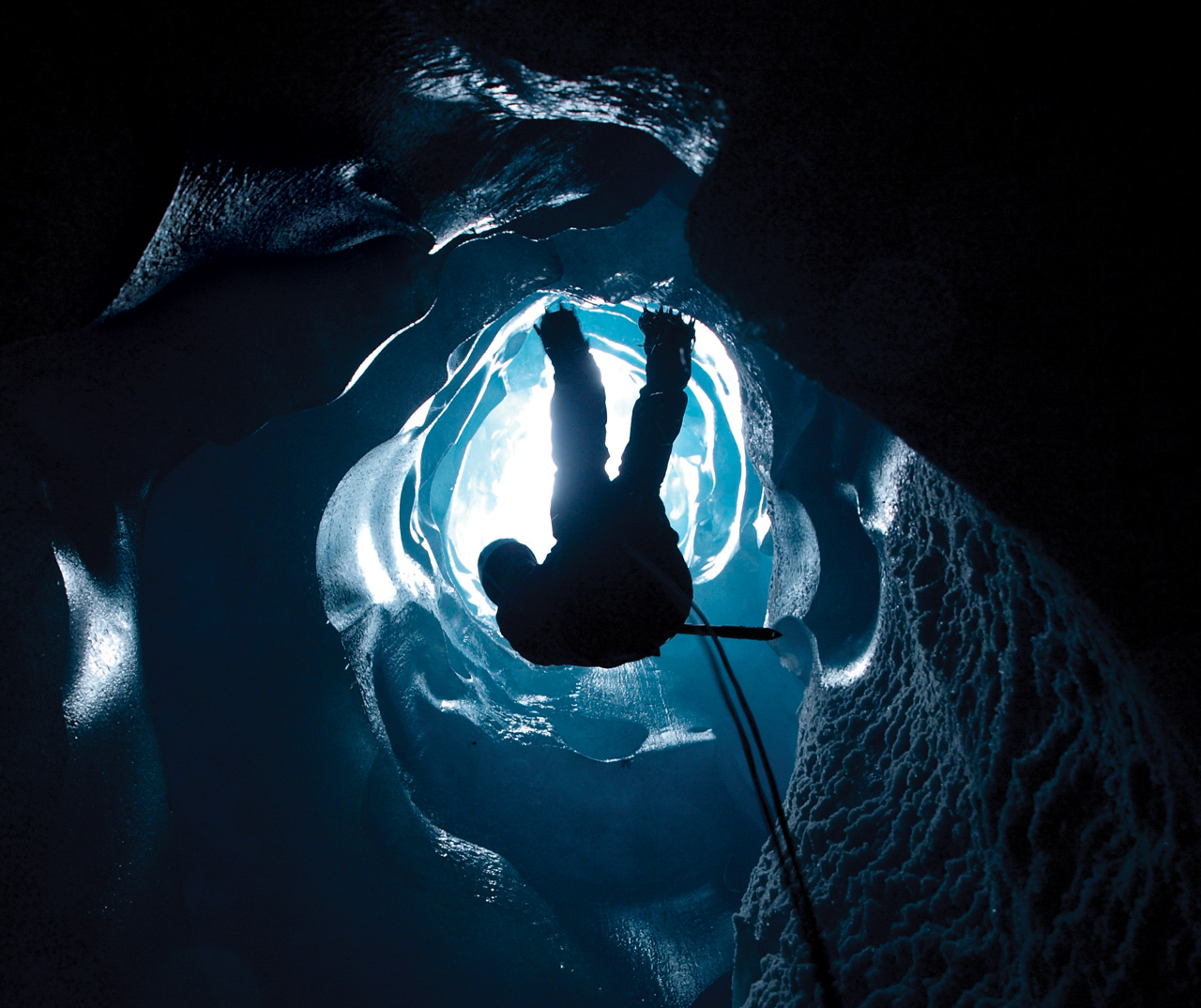

Hiking with friends on Jostedalsbreen, each of them tied together, she’d noticed a tiny brown lemming frozen beneath the ice, then several more. And just moments later, she fell into a crevasse, “like ice in a glass,” she would later write, her body dangling from the rope like a fishing lure. She wondered if there wasn’t some connection to be made between the lemmings and the fall, a method of braiding one with the other to make sense of both.

She used the resulting essay in her application to the University of Missouri, where she enrolled in the doctoral program for literature and creative writing in 2009. Visiting writer Nick Flynn, author of the critically acclaimed memoir Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, suggested she expand the essay further, teasing out a thread on Walt Disney. Author Maureen Stanton, now her professor, suggested she expand another on the Atomic Age. Before long, she’d revised and published “Glaciology,” the first essay included in her debut collection, Dispatches from the End of Ice, released last year via Trinity University Press.

“We went back and forth over the metaphoric energy around that for her essay,” Flynn says, “and I’m very glad it has made it into the world.”

Comprised of 14 exploratory essays, each one unique in its form and juggling multiple narratives, Dispatches from the End of Ice probes the meaning of loss from both a personal and environmental perspective. Along the way, in often lyrical prose, she introduces readers to a panoply of historical, mythical and scientific oddities: a giant chasm Norwegians called “Ginnungagap” where life supposedly began, a scheme to solve the United Arab Emirates’ freshwater shortage by towing a massive iceberg from Antarctica, the search for Sir John Franklin’s missing ship near Baffin Island in 1848 and the discovery of his shipmates’ cairns over a decade later.

“The book is the result of rigorous and relentless curiosity,” writes poet Kate Northrop, a friend and former professor at Wyoming. “It’s beautiful.”

Today, Peterson lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where she teaches creative writing and book editing at Grand Valley State University. She is researching her next collection of essays, loosely focused on space and a parent and a friend’s cancer. The central question of that new book is, “Does what’s out there matter in light of what’s happening now and here?”

“I love creative nonfiction, in part, because I can get out and do the boots-on-the-ground work,” she says. “The immersive nature makes it exciting.”

Deftly ushering her readers through the crevasse, beyond the glacier, back in time and across the page, perhaps Beth Peterson is still a wilderness guide after all.

Read an excerpt from Dispatches from the End of Ice below.

The long quiet

How does it feel to tumble into a crevasse, and what goes through a hiker’s mind while dangling from a safety rope, hoping to see the sun again? In this excerpt from Dispatches from the End of Ice, author Beth Peterson shepherds us across ice caps and their cultural terrain.

It’s quiet on the glacier — and not the good kind of quiet. It’s the long quiet — the quiet that splits you open, leaves you flayed.

I try yelling.

“Matt —”

“Adam —”

“Lydia —”

“Help —”

Nothing. Only low rumblings in the distance and the faint sound of water running, probably rainwater or melted snow, dripping through thin tears in the ice, pushing downward, drips becoming streams, streams becoming wide rivers of glacial runoff, pouring down the base of the mountain, splitting into the glacial valley, cascading into the fjord and then the Atlantic Ocean.

When my eyes adjust to the semidarkness of the crevasse, I size up the hole. I’m hanging midway between parallel walls of raw ice, thick and slanted and buckling in places. There’s an overhang two stories above; I see the outline. Shards of snow crack off it every few minutes, fall past me or onto my back and arms. Somewhere above the overhang, there’s a shaft of sky. Beyond this, the only thing I can make out clearly is a thin blue line, edging the glacial walls many stories below.

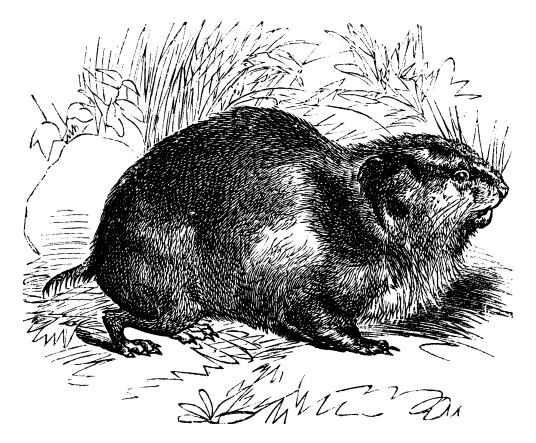

It was the summer of the lemmings: the fourth year in the four-year cycle of boom and bust, massive population explosions then sudden and devastating dives; in the course of a few months, sometimes weeks, Norwegian lemmings fall off cliffs; they walk into rivers; they climb onto long sheets of ice and sun themselves to death. In a single area, populations swoon from several thousand to near-extinction.

No one knows exactly why this happens. Some scientists say that the Norwegian lemming deaths are caused by the early thaws, then late spring freezes that melt the tunnels, that put the lemmings on the top of the ice, bare and exposed. Lemmings burrow, create long, low caverns beneath the upper layers of snow. When the snow melts early, they can freeze in a single cold morning. Others say that it’s a stress mechanism: There are too many animals in one place, and in their sprint to get away from one another, they run off cliffs, they dive into deep pools of water, they expose themselves to the elements.

In the 1960s, scientist W.B. Quay suggested that in the every-few-year combination of bursting lemming populations and increased temperatures, something inside the lemming’s brain becomes unbalanced. Abnormal deposits begin to show up in their blood, and the lemmings begin to move at a frantic pace. These deposits shut off normal responses of the animal’s brain until the lemmings can’t eat, can’t dig, can’t reproduce, can’t do anything but move in frenzied circles, in large groups, until they exhaust themselves to death. “It is mass hysteria,” wrote Ivan T. Sanderson in 1944, in the Saturday Evening Post, of a summer of the lemmings. “There is no turning back. These timid, retiring animals have lost all their natural sagacity.”

I didn’t know about the lemmings that day on the glacier, but I’m not sure it would have mattered if I did. All summer my friends and I had been eager to get onto the glacial ice. I’d hiked there once before, but it was the first time for most of my friends, and none of us was from Norway or from places with similar topography. We were driven — it seemed — by the idea of traversing a private plane of ice, of finding ourselves in a landscape that was both swelling and drifting off-center at the same time. Plus, this would be our first chance to do real, technical climbing: lurching across 5-foot-wide crevasses, scrambling up and down nearly vertical surfaces, inching over hollow ridges of ice, past deep wells of water, a thousand feet below.

We got up early that day, took the first bus and arrived at the glacier before breakfast. It was clear, dry, and sunny and mostly cloudless that morning. Unlike the rest of Norway — wet and green — the high glacial mountains are dry, cold, austere: brown grass plains flattened by heavy snows giving way to sharp angular slopes and broad block fields of jagged rocks. When there’s no snow or rain or fog, you can see the backside of several summits in the distance, snow crusting over their ridged outlines, then dropping five or six thousand feet to broad rocky valleys. Beyond the tall mountains, miles of high plains and lesser peaks, gray and muted — even in the summer sun — seem to stretch straight to the sea.

Unlike some other sections of the glacier, this one took more work to get to; after we got off the bus, we hiked, for some time, down a single-track trail, over cold knee-deep streams and long washes of mud, before we made it to the perimeter of the glacier, the place where hundreds, maybe thousands, of feet of compressed snow met rock.

At the edge of the ice, our guide, Matt, took a rope out of his backpack and the other six of us began putting on our gear. Then we began hiking: sinking knee-deep in snow, yanking a leg out, finding some tenuous sense of balance and repeating. The snowfall was recent, had come late to Norway that summer. Snow’s always riskier than ice, especially on glacial summits like this one, summits that had an early thaw, then a late last storm, hiding the crevasses — long, low cracks — that spread like a graph up the mountain.

By an hour into the hike, sweat and snow had already soaked through my gloves and the cuffs of my pants. It had become rhythmic: Our boots sunk into deep snow, then we climbed out of it and then sunk back in and we climbed back out, stopping between the sinking and climbing only to relash on the metal crampons that were made for ice, not unsteady surfaces.

We were finally heading out of the first snowfield — toward the larger ice forms at the top of the glacier — when I noticed it: a brown spot on the ground, just to my left. It was too dark and even-shaped to be mud and too far from the trailhead to be a rock or a patch of dried grass. I stopped, and the guy behind me — a lanky 20-year-old — stopped, too. “Are you all right?” he called to me. When I didn’t answer, he walked up to where I was standing. I pointed to the spot: “Look at that.” He looked for a moment and then crouched down and kicked at the brown spot with the toe of his leather boot, cracking the thin layer of ice that was covering it.

Underneath the snow and ice was a small, frozen animal: a lemming.

In the 1950s, Walt Disney’s White Wilderness became the first documentary to film the lemmings’ dramatic deaths. The climactic scene taped hundreds of lemmings “migrating toward mass suicide” in Alberta, Canada, brown and white bodies falling, sliding, scrambling over the northern Canadian terrain in a frantic pack. They pushed down and up and into one another, all tracking a single lemming in front, until they reached a high cliff. The leader jumped: flew gracefully through the air toward the water. Then the rest jumped, and hundreds of lemming bodies, all on tape, were raining into the Arctic Ocean.

Except that 1958 wasn’t the year of the lemmings. And it wasn’t an ocean; it was a river, and the filmmakers had paid 25 cents per lemming, gathered hundreds of them, put them in cardboard boxes for keeping, then onto a spinning white turntable, which they angled up and down until they got the camera shots, and then they pushed those lemmings to their deaths, off the turntable, toward a long, low cliff angling into the water. Some people say they see the lemmings hesitate when they watch that movie, that they stop slightly, for a second, before they jump.

Norwegian lemmings are the only lemmings whose populations fluctuate randomly, who die in such massive sweeps that they almost don’t come back. Collared lemmings, the type of lemmings that live in Canada, in the United States, in most of the places other than Norway, don’t live in packs and they hardly ever migrate.

We were gradually making progress up the mountain — following the shallow recessions of each other’s footsteps straight through the hard glare of the high alpine light — when all of sudden, without warning, I felt it: a sharp jerk on the rope.

I looked up just in time to see our guide, Matt — 10 feet in front of me — stumble slightly and then lose his balance altogether, his small frame hurtling straight into the snow. He swung his arm out, grasped for the rope and threw his yellow backpack behind him. Still, a second later both his legs were gone, plunged in waist-deep.

I stopped, as did everyone else behind me. The snow had been wet all day, but it was the first time any of us had slipped in beyond our knees. “Are you OK?” I called to Matt from behind, holding one hand on the rope and kneeling to feel the ground myself. It was firm, solid, virtuous: an Illinois cornfield in winter, a Wyoming road in the middle of March.

In one smooth step, Matt leaned forward, yanked his legs out of the snow and righted himself. He brushed his pants off, then bent down and jammed the metal handle of his pickax into the snow a few times, the way he had done every few minutes along the way — shallow holes, concentric circles — mapping our path up the glacier. He picked up his backpack and started ahead.

“Walk,” Matt called back to the rest of us, still standing.

I adjusted my backpack and gloves and then I walked on, veering wide of the hole where Matt’s leg had sunk, just past the path of circles he’d made with his ax. At first, the path was fine — steady walking — but as I got to the final circle, the snow suddenly felt wrong, strangely light and loose, less like an icy corridor and more like a frosted-over creek at night.

Realizing what was happening, I threw my body forward, but I was too late. One of my feet started slipping, and then the other, and then I was gone.

Initially scientists believed the Norwegian lemmings’ cycles were tied to the cold. In this thinking, the lemmings’ migrations were an effort to get away from cold. The theory made sense: The mosses lemmings eat freeze in ice; the thin layer of snow where they dig tunnels and nests cakes over, hard, forcing them to find lower ground. But then, in the 1990s, biologists began to notice an unexpected phenomenon. Despite rising temperatures, the lemmings’ population peaks were falling. Plows were no longer scraping dead lemmings off the roads, and there were no longer lemmings’ carcasses at the edges of rivers, contaminating water supplies.

Biologists began to say it wasn’t the cold but the heat that is a problem. In cold weather, the snow’s consistency stays relatively constant; the lemmings can camp out below the snowpack, tunneling in deep and eating everything around them. When winter temperatures are too high — spiked by man-made emissions, greenhouse gases and fossil fuels, the same rising temperatures that crack ice, fracture glaciers, create crevasses — it’s then that the snow melts and frozen water floods the lemmings’ tunnels until they collapse, drowning some, forcing others to freeze to death, suspended between snow and ice.

Five minutes. I feel nothing, nothing except my right leg pounding like it has a heartbeat. The tip of my ax is dark and wet, and there’s some blood gathering around my sock; my pant leg is torn from the ax; one metal crampon hangs off my ankle. Otherwise I’m fine, or numb; I’m not sure. I’m sweating and shaking, and I don’t want to take off my gloves to see whether the tips of my fingers have begun to turn blue.

I heard it first, before I felt it — the weight of my backpack and my body and the fall — snapping hard against the single knot that held me. I lurched, the rope burning against my legs and my waist as my body moved forward and the rope yanked backward, careening between one wall of ice and another. But then, as suddenly as it began, it stopped: I stopped, faceup, hanging in midair. And then it was quiet.

It had been quiet ever since — and more than anything, more than the distance I’d fallen, more than the thin rope or the overhang, it was the quiet that worried me. Needing to do something — anything — I decide to swing the rope I’m hanging from back and forth in hopes of gaining momentum and wedging myself against one of the walls.

I hold the rope close to my chest with one hand and begin unleashing things from the side of my backpack with the other: some food, a couple of bottles of water. One at a time, I shed things into the dark below me. When there isn’t anything left to drop, I rehearse the plan in my head and pick a spot on the wall that I’ll aim for. I swing back and forth three times before I decide to go for it. I grab the rope harder, bend my knees to my chest and then hurtle toward the wall in front of me, slashing my ax above my head.

I’m too far from the wall to get any traction, to make meaningful contact; I hit the ice, hard, but I bounce off it as a slab of wall breaks and barely misses my back and falls into the darkness below.

I watch it drop, then I put one hand just under the knot and stretch my other arm straight out to keep my balance. I don’t move; I don’t yell. I just hang there shivering, wondering, if I wait long enough, whether the high canyon walls will come together like stairs, will lift me.

Almost immediately following Disney’s death in December 1966, rumors began to circulate that he had been “frozen alive,” his body stored alternately in Disneyland or in Glendale, California, in a large vault, on ice, until some day in the future when scientists could medically resuscitate him. Later some of Disney’s biographers suggested that he had volunteered to become America’s first cryonics patient, meaning his just-dead body would have been injected with antifreeze, cooled to the temperature of liquid nitrogen — negative 321 degrees — and stored in a body bag in a capsule, in “suspension.” Disney’s family and friends strongly refute this, though they concede that he was perpetually anxious about his inevitable demise.

It wasn’t just Disney, of course. White Wilderness was filmed at the height of the Atomic Age, a mere 10 years after Little Boy and Fat Man were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For the first time in history, it seemed, it was possible to annihilate the entire human race in just a few swift blows. “I realize the tragic significance of the atomic bomb,” President Harry S. Truman wrote in a 1945 statement to the American people. “It is an awful responsibility which has come to us. … We thank God it has come to us, instead of to our enemies, and we pray that He may guide us to use it in His ways and for His purposes.”

Death had become a feature of the American national psyche; weapons of extermination had become gifts, products of American industry and ingenuity. Photos and video footage of the victims — flash-burned by radiant energy released in heat and light — were classified, hidden. Yet the effects and fallout of the atomic bomb were felt around the globe from Tibet to Greenland and even to Norway’s glaciers. In fact, the advent of the atomic bomb changed glacial dating. It was at this point that scientists began to date glacial accumulation and recession by studying radioactive fallout conferred in two layers from the 1951 and 1963 atomic bomb tests.

“Our films have provided thrilling entertainment of educational quality,” insisted Walt Disney of his collection of nature films, including White Wilderness, “and have played a major part in the worldwide increase in appreciation and understanding of nature. These films have demonstrated that facts can be as fascinating as fiction, truth as beguiling as myth.”

The myth of the lemmings took off: newspaper comics, commercials, video games. In his 1976 children’s book The Lemming Condition, Alan Arkin tells the story of a young lemming named Bubber who is the only lemming to question the plans to jump into the sea. “What do you think it’s going to be like?” Bubber asks an adult lemming, Arnold. “How should I know?” Arnold responds . . . “radiating peace, calm and disdain.”

In a 2008 bid for the U.S. Senate, Oklahoma candidate Andrew Rice took the myth even further, using the lemmings scene from White Wilderness in his advertising campaign. “Washington politicians,” the ad’s narrator says as the brown lemmings begin moving through brown grass and over rocks, “are a lot like lemmings. They follow their party, even if it’s over a cliff.”

I should have been prepared; we prime ourselves for accidents out there, practice clotting wounds, treating frostbite, splinting bones with long, narrow hemlock branches. In my wilderness guide training, we rushed into cold rivers and let ourselves go, into the thrashing current, so someone else could throw out a rope and feel what it’s like to save somebody, or to not try hard enough and to watch a person begin to drop, down, into the shimmering deep.

I should have been prepared, but I was not. I hadn’t banked on seeing the lemming. How could I? I would ask myself later, more as an excuse than a question. When I saw the lemming that day on the ice, it didn’t look stuffed, like I would expect from the dead or the dying, or breakable, like a paperweight or a pool ball. Shorter than a field mouse but thicker, it was light and wet, like an infant still in fluid, and trembling — though that may have been the wind, or me, pressing up against it, shivering. Its eyes were dark, but its ash-brown hair was caked in a thin layer of snow.

I crouched down next to the lemming, as soon as I realized it was an animal — not some dirt or a rock or piece of trash or something else someone had left behind on accident, dropped from a pocket, out of a backpack, never recovered — and touched it lightly with my glove. It shook slightly. I didn’t know what to do: to cover it back in snow, to warm it, to wrap it in a hat or jacket or my bare hands, to see if it might be revived.

I did none of these things. “Walk,” Matt yelled back to the rest of us. The whole line was stopped by this point, waiting for me as I looked at the lemming. Behind me, my friend Adam hiked a few paces back to his place in the rope line and pulled the rope tight between us. I stood up, too, dusted the snow off my pants and gloves, and then I moved on, leaving the lemming lying in the snow, exposed.

As I began walking up the glacier, though, I saw another brown spot to my left — dark, even-shaped, just below the ice — and then there was another brown spot just ahead of me. Soon there were half a dozen brown spots lining the path, breaking through the surface. We were surrounded by dead lemmings, shaggy, gaunt and encased in ice.

In 2006 — partway through my first summer in Norway — a team of scientists, under the leadership of Ohio State glaciologist Lonnie Thompson, set out to analyze one of the world’s most remote glaciers, the Himalayas’ Naimona’nyi glacier, by collecting ice samples from the infamous 1951 and 1963 radioactive fallout layers.

Thompson — who is renowned for having spent more time than any other living soul at over 20,000 feet — expected some change in the glacial ice. Patagonia glaciers, after all, had retreated almost 1 kilometer in the prior two decades, Swiss glaciers had lost 500 meters in the prior three years, and five Norwegian glaciers had receded over 100 meters each in just the prior year. At 25,000 feet — looming above the world’s highest plateau — Thompson and his team assumed rightly that the ice would likely not be the same as when it had last been measured.

What they didn’t expect was that the atomic fallout layers would be completely gone, that there — in the center of the universe, the place that Hindus call the devatma or god-souled land — all that ice would have already melted.

Sometime later a friend would ask me why, after that day on the glacier, I began to care so much about the lemmings. What he meant to ask, I think, is why — those days in Norway and then even once I had moved home — I got obsessed with lemmings, why I taped color photographs of lemmings on the wall and why I talked about lemmings when we were scraping paint from the back of the house and when we were lying, stretched out slim, in separate seats on the city bus. I checked out a small stack of rodent books, underlined important phrases in life-cycle field reports, but I never did answer his question.

You see, whatever Disney’s reasons — if he had them — for perpetuating it, the myth of the lemmings became big: bigger than White Wilderness and bigger than a ploy against collective bargaining or an admonishment about the perils of groupthink. The story of the lemmings, it seems, came to offer a measure of control, a reverse moral where rugged American individualism alone plays the trump card against the terror of death’s long edge.

But there is no trump card. What I’d like to tell my friend now is this: I once imagined myself constructing an alternate life in Norway: painting houses, buying groceries at the local shop, walking along the green coastline, watching the early morning light sweep up the cool wet night. It would have been a measured life, a controlled life, and not a real one. There is no night in the summertime in Norway, though sometimes the afternoon light, all at once, is blinding.

That day on the glacier, I heard Adam first, then Lydia, both muffled.

“You’re OK.”

“We’ve got you.”

“Get me out of here,” I yelled up.

“We’re working on it,” Adam called back, again muffled.

A few moments later there was a sharp pull on my waist, and then snow was falling around my shoulders, chipping off the open side of the crevasse and sliding down in sheets as my friends Adam and Steve yanked the ice-caked rope over the edge of the hole. Suddenly, the rope and my backpack and my body began to lift, one arm’s length at a time, up toward the light and the others’ voices and the long plane of ice and snow above.

About the author: Beth Peterson, PhD ’14, published Dispatches from the End of Ice (Trinity University Press, 2019).

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.