Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 17, 2021

Story and cartoons by Michael Shaw, MA ’92

To Michael Shaw and numerous other New Yorker magazine cartoonists, the late James Thurber is both founder and high priest of their famous and nutty club. In 2009, Shaw made a pilgrimage to Thurber’s home-cum-museum to deliver a presentation. But his adventure there that dark and stormy night is fast becoming the stuff of legend — not to mention a rash of Google searches on paranormal cartooning. Was what he saw that night real, a manifestation of his obsession with Thurber or maybe the result of ingesting one too many cheddar cubes at the reception? You be the judge.

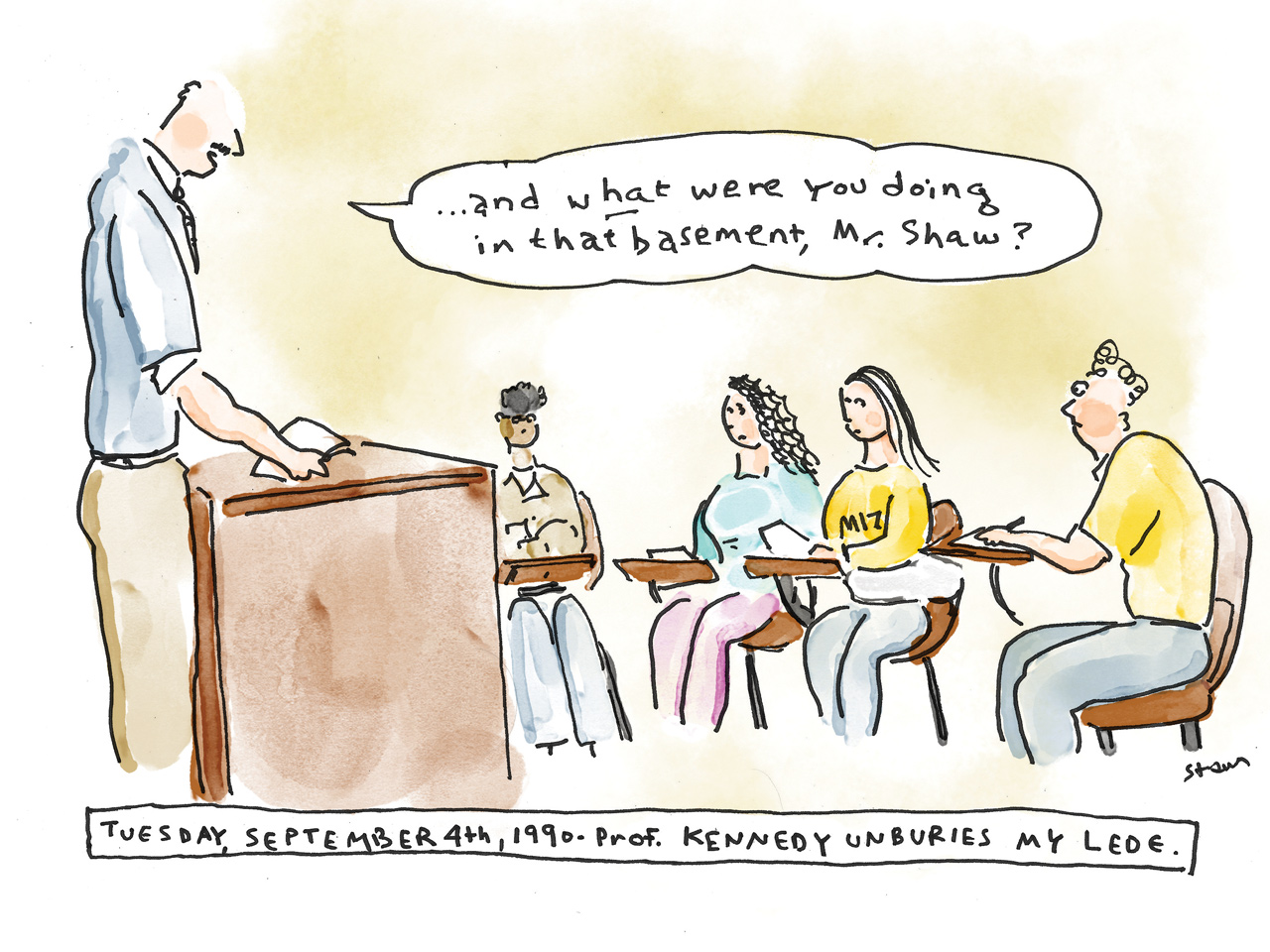

Once you have a class with George Kennedy, he’s always in your head. And so, fearing burying my lede, the No. 1 journalistic transgression he impressed upon us in Newswriting 101, I’ll get right to it.

There I was: 77 Jefferson Ave., Columbus, Ohio, 3-ish in the morning. Alone in a basement. The former basement of legendary humorist and cartoonist James Thurber.

“When were you in Thurber’s basement, Mr. Shaw?” George would have asked.

“May 1, 2009,” I’d have crisply replied. (It’s always important to get the reporting out of the way, so one can get on with telling the story.)

With that, George would have nodded in approval and asked, “And what were you doing in that basement?”

I’m not quite sure.

And that’s the truth — but here’s the rest of the story.

A case of chronic thurberitis

Full disclosure: The events that follow are unverifiable, but it’s my story and I’m sticking to it. If one of the most storied houses in the history of humor had any skeletons or ghosts anywhere on the premises, my mission was to make contact. (Including Muggs, Thurber’s recalcitrant terrier, reportedly still patrolling the house in spectral form and retaining a taste for mortal derrieres.) So, the wee small hours of May 1, 2009, found me poking around in boxes in the cellar of the Thurber House. Why? Blame it on a flare-up of my lifelong affliction of Thurberitis — a self- diagnosed and largely self-inflicted and uncurable cartooning malady.

Just to be clear, I hadn’t broken in. I was invited.

The letter from the museum’s executive director began, “Your cartoons in The New Yorker magazine and your lifelong connection to James Thurber compel me to write to you.” The request? To speak and present my own cartoons at a “special cocktail reception” and opening of their 25th-anniversary celebration. This bit of shameless flattery proved irresistible: “But the real thrill would be having you speak about your ‘relationship’ with Thurber and the special way of cartooning both he and you share.”

The Thurber House, an attractive Victorian three-story, served as the family home from 1913 to 1917. Thurber’s distinctive oeuvre of short-form reportage, fiction and fables slots him neatly between Mark Twain and David Sedaris in the pantheon of white, male humorists.

But it’s Thurber’s vernacular and peculiar drawings, described by Dorothy Parker as having “the outer semblance of unbaked cookies,” that to this day continue to stick in the creative craw of many a cartoonist. Including me.

It was in this smallish, spooky-ish place (especially in the wee small hours) that I had invited myself to a sleepover. The Thurber House was now transformed into a museum, gift shop, gallery and learning center. Writers and humorists resided there while completing novels, teaching classes, judging writing contests, overseeing festivals. I just wanted to sleep in the attic.

Clues in Christmas landscapes

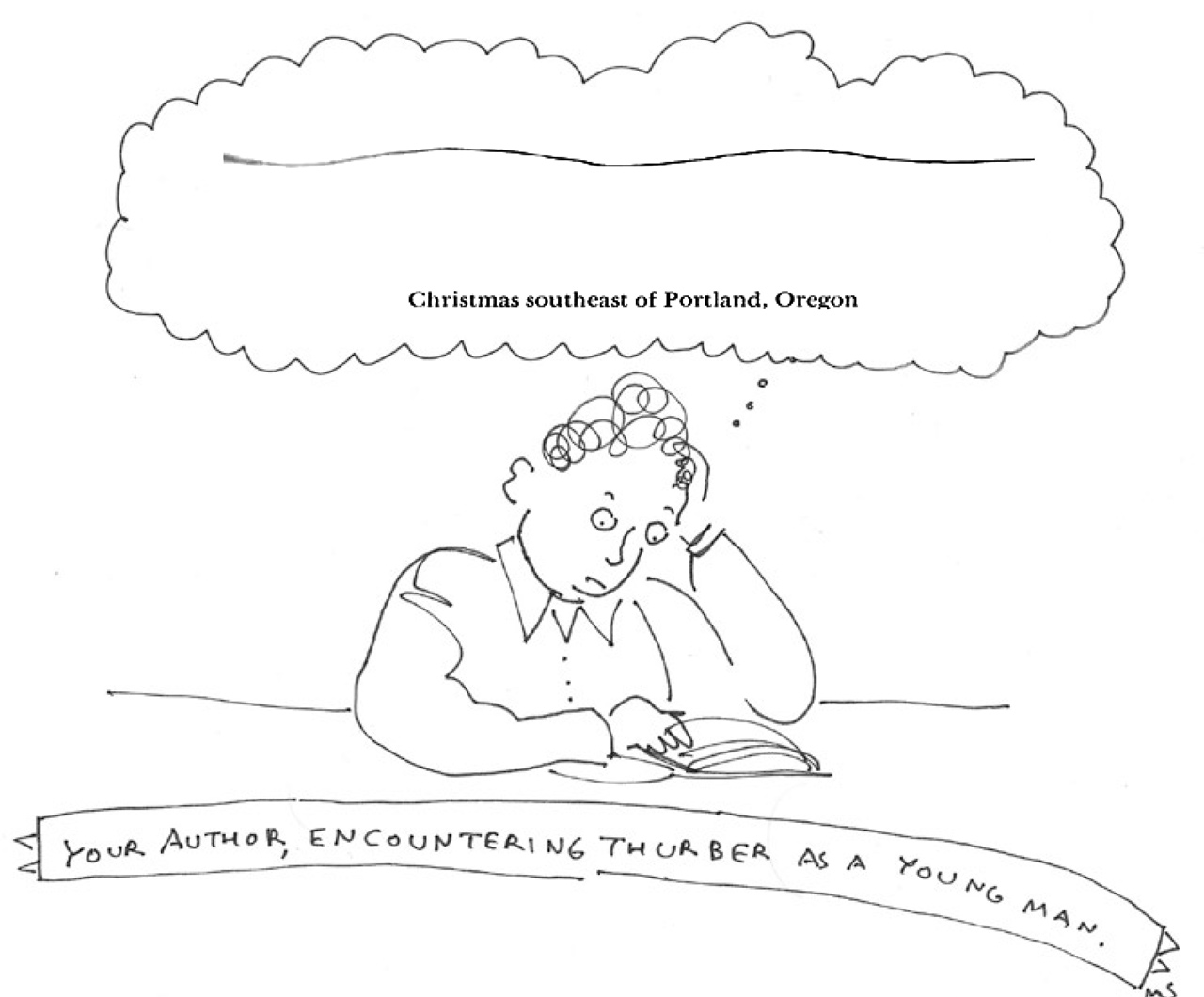

My initial Thurberitis exposure traces back to the book Thurber & Company. I discovered it under the tree one Christmas morning in 1968 while tearing through the usual swag of Hot Wheels and G.I. Joes. Technically, the tag indicated the book was “from” Santa and “to” my brother Patrick. But ethics hold little sway during the bloodlust of present opening. (I still retain disputed possession).

I paused at pages 38 and 39, transfixed by four drawings of Christmas landscapes, titled Near South Bend, Indiana; Carson City, Nevada; Not Far from Omaha; and Southeast of Portland, Oregon. All four were single curving lines dotted with tree- and house-like doodles. Portland was merely a line. I had no idea who this Thurber was but knew he was certainly getting away with something.

A regular diet of Marvel Comics and the daily comics section of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (which, foretellingly, included Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey plus Hi and Lois) kept my Thurberitis in remission during grade school. High school was a different story. The purchase of My Life and Hard Times — which I still possess, though it’s looking a little worse for wear, from the Book Nook in De Soto, Missouri — finally put cartoonist and writer together.

Fiddlin’ with his pistol

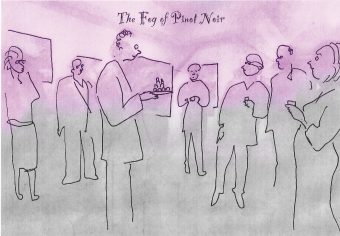

In 2009, I was nearly two decades removed from my J-School days — fearlessly confronting the world as a copywriter/cartoonist/humorist with various degrees of success. But one part of the invitation that really caught my eye beyond a modest honorarium was “All the wine and hors d’oeuvres you can eat!” (A Pavlovian reaction from my earlier academic career, earning a BFA in painting from Webster University in St. Louis, where I subsisted on a steady diet of gallery opening fare.)

My recollection is that the evening went well. The actual events remain a bit fuzzy. Perhaps the only miscalculation being my capacity to process a surfeit of gallery-quality red wine and cheese cubes. I looked forward to entombment in the Thurber House for the night.

My recollection is that the evening went well. The actual events remain a bit fuzzy. Perhaps the only miscalculation being my capacity to process a surfeit of gallery-quality red wine and cheese cubes. I looked forward to entombment in the Thurber House for the night.

If I had a bucket list, which I don’t, spending the night in the infamous “attic” described in The Night the Bed Fell would be near the top. That, or encountering “the Thurb” as a ghostly apparition, or perhaps his Airedale Muggs, who famously bit people.

Full disclosure No. 2: The house did have a haunting reputation. Thurber himself recounted hearing a ghost in the house on Nov. 17, 1915. Plus, an earlier tenant had killed himself in the dining room whilst fiddlin’ with his pistol. The house even sits on land previously occupied by an asylum that burned to the ground in 1868, killing six occupants.

I was ready for a big night of falling beds or rising ghosts. The director left me with this bit of advice: “Just don’t go outside. Opening a door sets off the alarm system.” And that alarm would prompt a visit from Columbus’ finest and a handsome bill presented to me for their troubles.

I was ready for a big night of falling beds or rising ghosts. The director left me with this bit of advice: “Just don’t go outside. Opening a door sets off the alarm system.” And that alarm would prompt a visit from Columbus’ finest and a handsome bill presented to me for their troubles.

The “attic,” it turned out, was now a pleasant studio apartment, complete with a sturdy, comfortable bed. Replicating a collapse of any sort was unlikely. Apparitions, apparently, weren’t in the offing, either. I drifted off with visions of ghostly terriers dancing in my head.

A clock somewhere struck 3-ish. I awoke. Had I heard something? A thump? A footstep? Muggs? I was still inhabiting an over-pleasant attic in a bed that showed no sign of collapsing with no way out. Heat lightning flashed from a distant summer storm. The windows were also sealed with alarms, so the air was close.

I could have dialed out, but to whom? Call home and confess to my wife maybe this wasn’t the greatest idea I’d ever had? Or dial “M” for melatonin? The excitement of the night before, along with the muscular merlot, had worn off.

So, like a ghost, I rose and wandered, eventually landing in the basement. Perhaps — just maybe — I thought I might have heard something. Or at least I wanted to hear something. Maybe a fellow apparition? Why not the Thurb himself, patrolling the house in search of a nightcap. I’d take a manifestation, an epiphany, anything. Right now I was only experiencing agita.

I wandered downstairs to the main rooms. The first-floor parlor, dining and living rooms had been restored to approximate the home during the Thurber years. My mind, which is too much of a busybody to suit me, imagined the stories I had read coming back to life. I could have gone back to bed and read the book, but I was in the book — this was the room where the ghost actually got in.

The only remotely modern media on hand was a portable RCA television perched on a rolling cart. There was no antenna. Connected to the set was a VCR deck that played a fuzzy, looping, black-and-white recording of Alistair Cooke’s 1956 TV interview with Thurber. I watched it four times.

I wandered down into the basement. It felt like a basement — dark, musty and cluttered. This was more like it. Surely, Muggs would be taking a bite out of my keister at any moment. But no. Just me and boxes of Thurber merch.

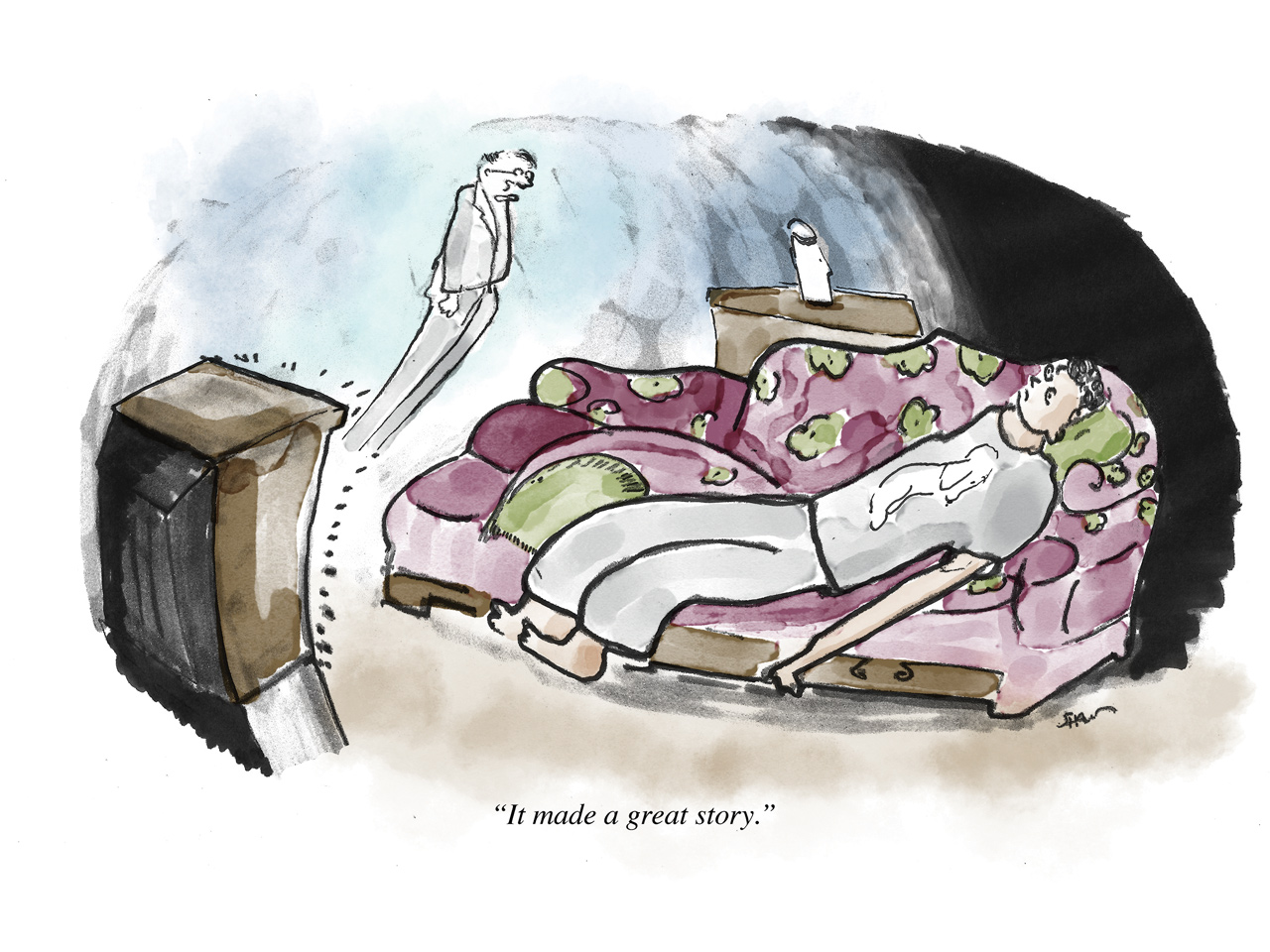

Back upstairs, I settled onto the horsehair fainting couch to watch Thurber and Cooke for the fifth time. There on the screen was Cooke — dapper, English, a man in his prime, smoking. And there was Thurber. Perpetually ill-at-ease — blind, bedraggled and looking a bit worse for wear, also smoking.

Back upstairs, I settled onto the horsehair fainting couch to watch Thurber and Cooke for the fifth time. There on the screen was Cooke — dapper, English, a man in his prime, smoking. And there was Thurber. Perpetually ill-at-ease — blind, bedraggled and looking a bit worse for wear, also smoking.

Their conversation wafted through the dark house and my wavering consciousness.

Cooke: “I can remember the shock of seeing your first scrawls in print. How do you ever get them published? No offense meant.”

Thurber: “Don’t look at me, that was E.B. White — Andy White.”

Cooke: “So, when you get into print, suddenly people think you have talent who had no use for you before?”

Thurber: “Quite a few of my drawings have been done by accident.”

Accident. That’s an accurate description of the events leading to this moment. It wasn’t exactly despair that descended on me but a moment of uncertainty of my purpose in this misadventure — like Linus doubting the Great Pumpkin.

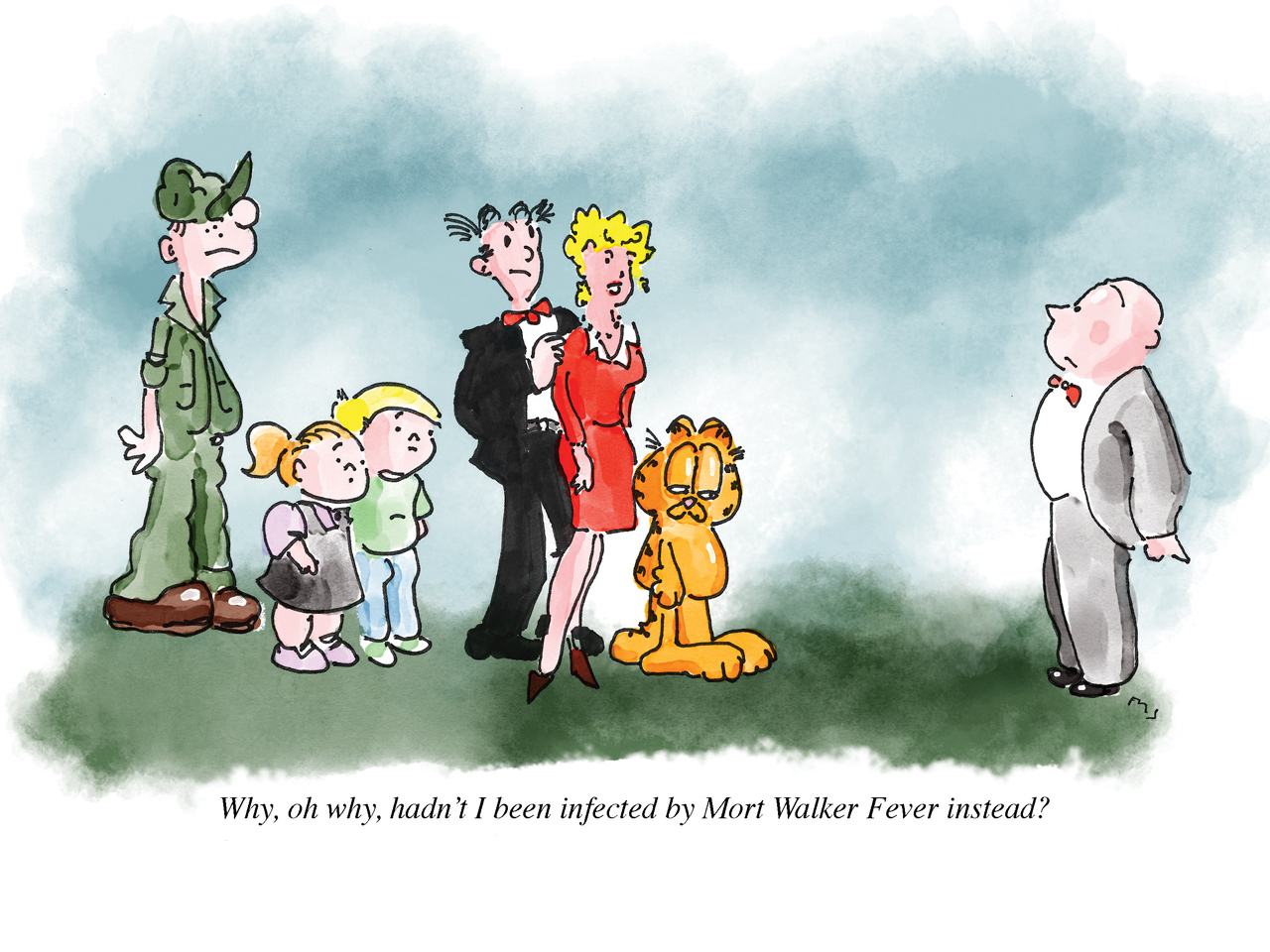

My busybody mind fought off sleep by shifting into I-told-you-so mode. As far as Thurberitis, why, oh, why, hadn’t I been infected by Mort Walker Fever instead? I was certainly sufficiently exposed as a graduate student, benefitting from an amiable and professional relationship with him. Mort was a genuinely swell and cheerful guy and introduced me to other affluent comic strip artists who greatly enjoyed one another’s company. I was not a good fit.

Truth was, my “fit” at the J-School had always been a puzzle piece that never quite found its proper spot. I had blustered my way into the graduate program back in 1989. I was fresh-faced (for a 35-year-old) and completely oblivious as to my course of action. In Newswriting 101, the aforementioned George Kennedy quickly diagnosed my uneasy alliance with the truth. He shuffled me upstairs to the office of Henry Hager — Yale grad and a copywriter from Madison Avenue’s golden age.

I presented Henry with my “book” of self-promotional samples, illustrated by my own drawings. “So, you’re a wrist?” he asked. I had no idea what that meant. To Henry, a “wrist” was a mock-up artist who could whip up a compelling rendering of a horse, can of Budweiser or a Ford Torino. No, I told him, I was more interested in cartooning — and writing. I think I croaked, “I want to be a writer, like you.”

Throw a shoe through the window

“Did you see it?”

Someone was speaking to me. I looked at the flickering TV. It was Thurber.

“Did you see the ghost?” He lit another cigarette and kept talking. “He walks around the dining room table. You’ll hear the footsteps first. If it’s too much, throw a shoe through the window. The cops will show up.”

“Did you see the ghost?” He lit another cigarette and kept talking. “He walks around the dining room table. You’ll hear the footsteps first. If it’s too much, throw a shoe through the window. The cops will show up.”

Even in mid-epiphany, I knew that wasn’t a great idea. But the Thurb would not be deterred. He continued, “It’d make a great story.”

I had to ask him the question — the question that Henry had posed to me a decade earlier. I was a cartoonist but also wanted to be a writer. True, my writing, unlike Thurber’s, primarily extolled the virtues of everything from button-down Oxford shirts to oversized barbecue grills. Both Thurber and White had escaped copywriter fate early on. Too late for me.

I asked, “Which did you enjoy more, drawing or writing?”

I already knew the answer but wanted to hear it straight from the RCA. The Thurb didn’t miss a beat: “If I couldn’t write, I couldn’t live, but drawing to me is little more than tossing cards in a hat.”*

* actual quote “A Conversation with James Thurber,” New Republic, May 26, 1958, p. 12

Epilogue for an Epiphany

Somewhere a clock in Columbus struck 7-ish. There I was: May 2, 2009, 77 Jefferson Ave. One word of advice if contemplating the purchase of a Victorian fainting couch — they’re not a great spot to faint or fall asleep upon. The TV was off, Thurber and Cooke tucked away in their VCR tape. I gathered up my stuff. It was morning, so the alarm system was off. I recalled the director’s last bit of advice: “The door will lock behind you when you shut it, so make sure you’ve got everything when you leave.” I did, and it did.

My epiphany arrived years later, while writing this story, as a matter of fact. Thurber would have called this the moral to the fable — but I will contend that these events actually happened. Mostly. College has been called a crucible through which you emerge transformed with an elevated sense of identity. College is also a salad spinner through which you’re whipped round and round but emerge fresh and tempting for society’s consumption. And to answer the big question — what’s all this got to do with why anyone would attend journalism school? — I think, ironically, Mort Walker summed it up best: “I knew how to draw. I went to the J-School to learn how to write.”

Thurber knew how to write and how not to draw. I’m still learning to do both.

About the author: Michael Shaw is a writer and New Yorker cartoonist. His latest book is The Elements of Stress, co-written with Bob Eckstein, with whom he also co-hosts the The Cartoon Pad podcast. Follow him on @shawtooner_on_a_fridge.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.