Nov. 8, 2021

Contact: Eric Stann, 573-882-3346, StannE@missouri.edu

Over the last decade, John Huntley, a paleontologist and an associate professor of geological sciences at the University of Missouri, has studied the history of parasite-host interactions. These interactions can occur either outside a host’s body, such as a tick, or inside a host’s body, such as a flatworm.

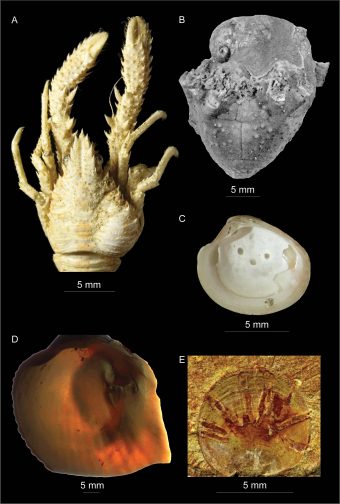

Recently, Huntley and his colleagues developed the first known database of parasite-host interactions among animals living in the ocean, including the fossilized ancestors of today’s crabs, shrimp and oysters. Their results were recently published in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

Huntley explains how studying fossilized parasites can contribute to our knowledge of infectious diseases.

How can studying fossil parasites contribute to our knowledge of infectious diseases?

We’re learning that paleontological research is more than a purely academic undertaking. Paleontologists have the privilege of studying ancient life and the environments in which these animals lived. By better understanding how parasite-host interactions have occurred in the past, we now have the primary evidence for how life has responded to a variety of calamities over hundreds of millions of years.

This insight can help us better understand the evolution of biodiversity over time, and give us greater context to modern problems such as the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change.

host skeletons.

What insights have you developed from your recent research on how parasite-host relationships have changed over time?

The first known occurrence of parasitism among animals occurred about 520 million years ago. Since that time, the occurrence of parasitism and the percentage of individuals affected by parasites has dramatically increased. In particular, the last 65 million years have seen an intensification in parasitism. This is consistent with my earlier studies of predator-prey interactions.

In general, we’ve found the world has become a more dangerous place for animals in the oceans over the last half a billion years. There are a variety of competing, but not mutually exclusive, ideas for why this has occurred, and arguments generally center around food chain processes, and changing nutrient and habitat availability.

What can these parasite-host relationships tell us about biodiversity and the health of ecosystems throughout the history of life on Earth?

We’ve found a strong correlation between parasitism and biodiversity. At the broadest scale, parasites are more common when there are more species. This makes sense because more species can mean more chances for developing these interactions. We also compared parasitism to the rate at which species originate and go extinct and found negative relationships, which suggests parasite-host interactions flourish when higher and more stable levels of diversity are present.

Therefore, we’ve seen evidence that parasites can positively stabilize coastal ecosystems that provide food and other services to millions of people in today’s world. Even though parasites harm the individual hosts that they infest, evidence shows they make the overall ecosystem more stable because of their actions.

To arrange an interview with Huntley, please contact Eric Stann with the MU News Bureau at 573-882-3346 or StannE@missouri.edu.

“Phanerozoic parasitism and marine metazoan diversity: Dilution versus amplification,” was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Funding was provided by FAU Emerging Talents Initiative SS16_NAT_11, National Science Foundation CAREER EAR-1650745, the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung Foundation, the Institute for Advanced Studies—University of Bologna, University of Missouri Faculty Research Leave and a Paleontological Society Arthur J. Boucot research grant. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.