Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 17, 2021

Story by Marina Shifrin, BJ ’10

Immigrants love reusable containers. It’s true. Even though I immigrated to America from Russia at 2 years old, my kitchen cabinets are still bursting with an extraordinary assortment of empty containers: pickle, salsa, caper — shape, size and material do not matter as I do not discriminate; I love them all equally.

My sample size for this odd stereotype is admittedly small: my family, my husband’s family and a few immigrant kids I’ve bonded with over the years. Still, I have yet to meet a true immigrant kitchen that doesn’t stockpile an array of recycled containers all cleaned, dried and ready to be used for whatever one might need.

Whenever my husband and I would fly up to Seattle from Los Angeles, his grandmother wouldn’t let us leave without a 32-ounce Dannon Yogurt container stuffed with her homemade chow mein. My own mother keeps a pharmacy’s worth of pill-shaped goodies in a trusty Altoids tin. Even though Olga claims to remember each pill’s purpose, she did recently slip me a couple sleeping pills for a headache. Your head can’t hurt when you’re knocked out, I suppose. There’s just something so inherently immigrant about wringing out as much purpose from one tiny vessel as possible — the fiscal conservancy, the refusal to create more waste, the imagination.

It took me years to learn what it means to be an immigrant in America. My first lesson came in kindergarten when my teacher, Miss Collins, asked the class to share what we wanted to be when we grew up. Lavinia wanted to be a scientist. Ben wanted to be a “powiceman.” Emily wanted to be a teacher. Melanie wanted to be a teacher. And then the class turned to me.

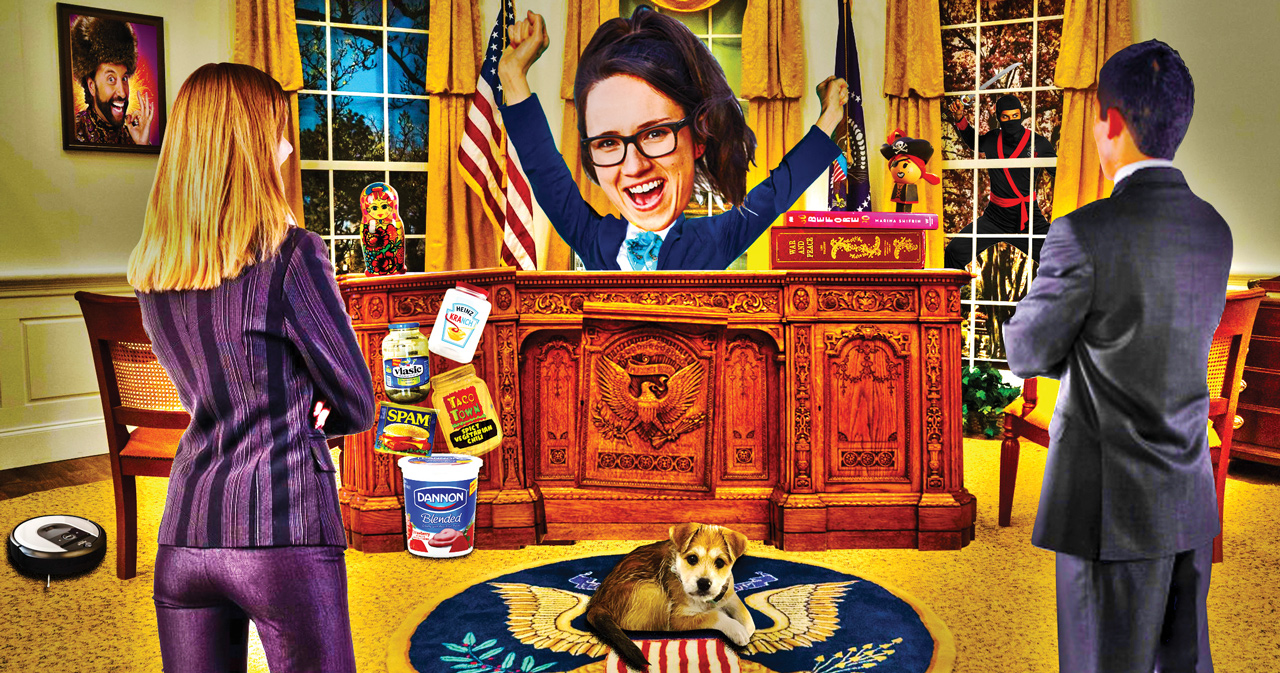

“When I grow up, I want to be president of the United States,” I told my constituents. Miss Collins shifted in her seat.

It was then gently explained to me that I could not “technically” become president because, well, the Constitution and all. I was encouraged to pick again. My answer quickly changed to teacher. (Note: I did not become a teacher, either.)

That evening, I walked home with my cousin Boris, a frail redhead whose answer to “What do you want to be when you grow up?” was “ninja.” Here was a child who hadn’t yet mastered potty training, but no one questioned his vocational choice of Japanese assassin. I, however, could never be president.

Having my quixotic dreams negated at such a young age was actually liberating. Butting up against an unmoving boundary at a time when the world felt impossibly large and shapeless taught me to quickly recalibrate and shift in a different direction. I became a little Russian Roomba, barreling toward walls and obstacles only to learn how to expertly navigate around them.

I’ve had a lot of lofty aspirations since that day in kindergarten, things like being the first in my family to graduate from a U.S. university (M-I-Z!), finding financial stability as a comedian, writing a book, cutting bangs by myself. I’ve accomplished some of these things and failed at others. However, I pride myself on being pretty successful at failing. The silver lining in hitting a lot of dead ends is that you eventually learn how to quickly and graciously move on. This ability to evolve past setbacks is what has brought me any successes I’ve enjoyed in life.

Ever since that day in kindergarten, I’ve been in a constant state of evolution. One week I’m a honey jar, the next I’m full of loose change. Being an immigrant has shown me the beauty of not letting impossibilities define who I can become.