Published on Show Me Mizzou Dec. 17, 2021

Educating physicians is a worthy goal for any university, but the MU School of Medicine goes one better — its mission is to meet the health care needs of Missourians. The school has gained national recognition not only for its educational achievements but also for increasing the state’s supply of rural practitioners.

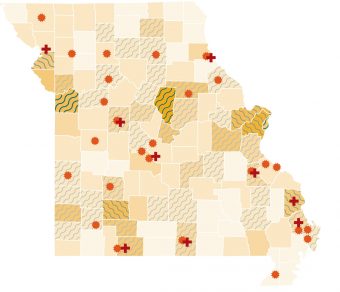

“Missouri faces a serious shortage and maldistribution of physicians in counties outside the major metro areas,” says Kathleen Quinn, BS Ed ’84, M Ed ’85, PhD ’09, associate dean for rural health. Although 18% of Missouri physicians practice in rural communities, almost 40% of the state’s population lives there. “If there’s not access to quality health care in a rural community, people’s health outcomes are worse, and their health care costs are driven up.”

Quinn oversees the school’s Rural Track Pipeline Program, a suite of successful recruitment and training programs for students from outstate Missouri and others considering practicing there. At the end of their sophomore year, 20 eligible undergraduates from rural Missouri are accepted into the Bryant Scholars Program and preadmitted to the school, where they meet faculty and learn about the medical school curriculum. When Bryant Scholars finish their bachelor’s degrees and enter medical school, they transition to the Rural Scholars Program, where any medical student can complete clinical training with community-based faculty in small-town practices at one or more of the school’s partner rural hospitals. “Students learn the breadth and depth of practicing as a rural health care provider, and they come to understand their role as a leader in the community,” Quinn says. Fully 55% of rural track students have gone on to practice in a rural community, and 80% stay in Missouri.

Regardless of where they eventually practice, all medical students must master core scientific and clinical knowledge for diagnosing and treating patients. At MU, that means spending the first two years of medical school learning their profession through lectures, labs and the patient-based curriculum. Introduced about 30 years ago, patient-based learning (PBL) pairs groups of eight students with a faculty facilitator. Clinical cases are at the center of it all. “The cases were developed so they unfold like a mystery, and students get engaged, searching for the hints they need to move forward and solve the mystery,” says Michael Hosokawa, senior associate dean of education and faculty development and the administrator who led the transition to this curriculum.

Unlike most other medical schools, which originally made patient-based courses optional, MU required that all first- and second-year medical students spend 10 hours a week working through the real clinical cases presented in the PBL curriculum. The result? Analysis of scores on national licensing exams shows MU as an outlier for its high marks. And 80% of graduating seniors identify PBL as the most effective part of their learning experience. “Students come here because of our patient-based learning,” Hosokawa says.

One-quarter of MU medical students finish their third and fourth year in southern Missouri at the Springfield Clinical Campus, which opened in 2016. By partnering with CoxHealth and Mercy Hospital, the School of Medicine has been able to expand its class size from 96 to 128. “The MU School of Medicine trains more physicians who go on to practice in the state than any other Missouri medical school,” says David Haustein, associate dean for the Springfield Clinical Campus. “Fifty-two of our students who trained in Springfield are in their residency or fellowship training programs, and we hope that by having spent a portion of their medical school training here, they will have developed a love of this part of the state and will come back to practice.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.