The campus was pristine the night Academic Hall burned. Fresh snow covered the ground and fell intermittently. The blanket of white was thick and pure. It was the picture of hope, the promise of a new beginning. It was nine days into the new year in 1892, four months into the fall semester and six months since the university’s new president had laid out big, bold plans in his inaugural address. Inside Academic Hall, people had begun gathering in the auditorium for an evening of entertainment when the chandelier crashed to the floor and the ceiling caught on fire. The dense smoke was the greater menace at first, but the flames kept dividing and consolidating into attack parties that would vanquish the building by midnight.

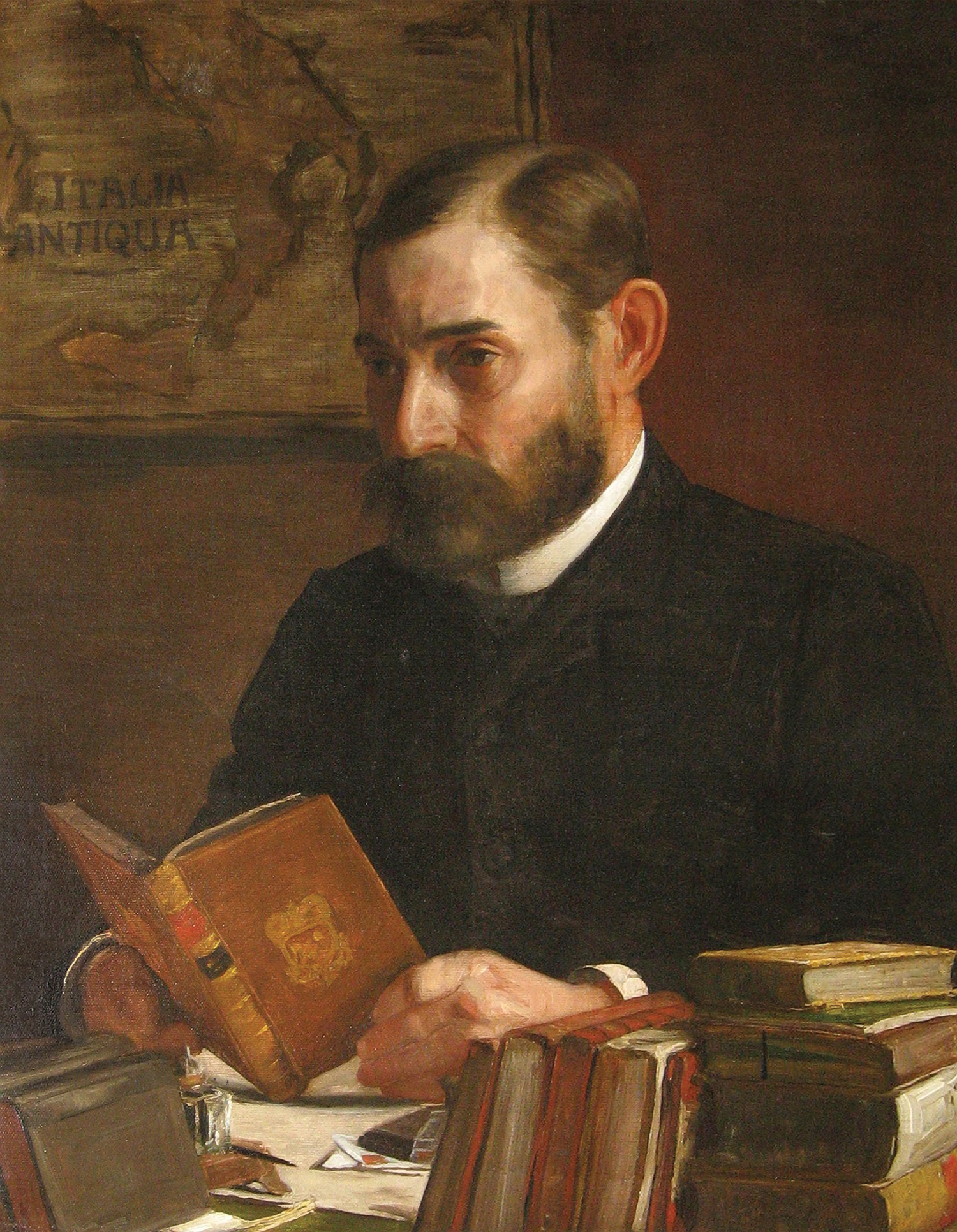

President Richard H. Jesse arrived on the scene before all hope had been lost. He strode about in the deep snow barking orders to remove furniture and equipment when it was still safe to do so. He entered the building himself, but smoke drove him out, and so he stood there, helplessly, in snow now stained by the lurid reflection of the raging fire. Jesse had come to Columbia with plans as grand as the edifice that was toppling before him, and he must have feared they were going up in smoke. “When Jesse is sworn in, virtually all of the university is contained in Academic Hall,” says campus historian David Lineberry. “Jesse hasn’t even been there one semester and is trying to get things going when literally 90 percent of his campus is destroyed.”

But whatever doubts Jesse may have felt about his future or his vision for the university didn’t outlast the long, sleepless night.

Academic Hall burned on Jan. 9, 1892, but from the ashes rose the modern university Jesse envisioned. During his 17-year administration, he transformed MU into a research-based institution where faculty not only impart knowledge but also expand it. He changed the curriculum from a prescribed course of study to the modern elective system and stressed the sciences as foundational courses. He declared in his inaugural address that “the old idea that Universities train men only for law, medicine and theology is gone from our land,” and, under his leadership, dozens of new fields of study fattened the course catalog. The man whose campus burned to the ground would later get credit for rebuilding it in more ways than one. In a letter to Jesse in 1908, the founding president of Stanford University, David Starr Jordan, wrote: “The University of Missouri was built in the early days by good men; the modern University has been your creation.”

Jesse, the firebrand

Jesse’s belief that higher education should be practical would have surprised his younger self, a Virginia plantation owner’s son who studied Latin in preparation for a life of leisure. With the collapse of the Confederacy came a reversal of fortune for Jesse’s family. By age 12, he was plowing fields and chopping down trees for cordwood. One of his chores — shelling corn — cost him three fingers on his right hand. Jesse worked his way through a private academy and two years of study at the University of Virginia. He quit for lack of funds, became a teacher, and, later, a professor and dean.

Jesse was just 38 when he became president of the university in 1891. Between his academic experience and his travels, he’d formed ideas about modern education and what universities needed as they headed into the 20th century. For most of their history, universities were teaching institutions focused on classical studies. After the Civil War, progressive universities began adopting the German model of higher education, encouraging faculty to cultivate knowledge through research and scholarship while training advanced scholars. Jesse embraced the German model and admired Johns Hopkins University, America’s first university founded for research and graduate studies.

Although a handful of researchers in the College of Agriculture had made names for themselves, MU wasn’t widely known at the start of Jesse’s administration. He nevertheless saw no reason why MU shouldn’t surpass other state universities and be on par with Johns Hopkins. That’s rather dauntless, considering what he found on arrival. “Here was this 19th-century, classically bound institution in this tiny, provincial place,” says Lineberry, associate director of MU’s Hook Center for Educational Leadership and District Renewal. Student enrollment was less than 500. The faculty was small and largely undistinguished. Graduate studies weren’t offered, but high school coursework was.

Undeterred, Jesse pressed on to strengthen the university he inherited and graft his ideas onto it. He created a master plan to retain and grow the agriculture college (he quashed a clamorous movement to make it a separate institution), develop the languishing medical department, and establish several new departments, deanships and professorships. He had expensive, audacious plans to equip labs, expand facilities and assemble a stronger faculty.

The loss of Academic Hall on that snowy Saturday put those plans in abeyance. Jesse and some other men remained at the scene of the disaster all night, evidently making arrangements to open the university on Tuesday, according to Jesse’s biographer, Henry O. Severance. (Monday was the weekly holiday.) Notices over the next two days assigned classes to makeshift classrooms around Columbia, including churches, storerooms and the courthouse. Jesse kept office hours in a room above a grocery store.

Because of the fire, Jesse spent the first two years of his administration focused on rebuilding. The new modern university sprang up around what is now Francis Quadrangle. Jesse urged state legislators to provide $600,000 to erect a new Academic Hall and five other buildings, which they did — after discussing and scuttling a proposal to relocate the university. With new buildings adorning the quadrangle, he turned his attention to reorganizing various departments and adding others. “He shows up at the helm and, before you know it, things resemble the modern university,” Lineberry says. “It’s not just the classics anymore. We’re researching biology; we’re defining journalism as a profession; we’re saving the world through medicine. It’s that whole concept of better living through knowledge. He’s the linchpin in all of this.”

Just judging by the faculty positions he established — including a chair of journalism in 1898, a sociology professorship in 1900 and a director of the Agricultural Experiment Station in 1895 — shows the expansion that Jesse orchestrated. But it does not illustrate “the growth of the University in the esteem of the people of the State nor of its vastly increased usefulness,” according to a 17-page board of curators document titled “Official Retirement of President Richard Henry Jesse,” which details his accomplishments.

In the curators’ estimation, establishing and developing a graduate department was “one of the most conspicuous signs of the growth of the institution” attributable to Jesse.

Jesse devoted the first 10 years of his administration to reorganization and expansion. All the while, he proved “eminently successful at developing an able faculty,” according to his biography, Richard Henry Jesse. Jesse changed MU’s hiring policy to reflect the modern ideal of meritocracy. Vacancies customarily had been filled by Missourians and Democrats, with efforts made to ensure that faculty represented proportionately the state’s major religious denominations. Jesse didn’t give a whit about a candidate’s religion or politics. He searched far and wide for the best person for the job. Homegrown candidates were turned down in favor of “Massachusetts Yankees or furry Canadians” deemed more qualified, Jesse wrote in unpublished memoirs housed at the State Historical Society of Missouri. In his own estimation, he built up a faculty of “incomparable quality.”

Devotion to research

Since its inception as a university in 1839, the University of Missouri had been expected to provide some public benefit. After the Morrill Act of 1862, the university’s land grant status carried an expectation that it would conduct problem-solving research. The federal government and, by extension, the American people funded the land grants, “so the idea was to give back to the people through knowledge and discovery that improves quality of life, promotes health and safety, and helps the economy,” Lineberry says.

During the latter half of Jesse’s administration, he made research central to the university’s mission. “While the growth of the University in other ways has been due to many influences and to many men, in truth it must be said that its progress in devotion to research has been due almost alone to the enthusiasm, encouragement, and inspiration of the President,” the board wrote. Jesse took every opportunity to remind people that a university’s function is “to investigate, to teach, and to publish,” as he told the National Education Association in 1901. Later in that same address, he added “the promotion of human progress” to the list of functions. In his annual report for 1908, Jesse reinforced his policy that every faculty member in the medical department “should devote, at least, half his time to original research, which, side by side with teaching, is considered an essential part of his work.”

Jesse took a special interest in all research conducted on campus, personally offering encouragement and ideas. For instance, he suggested in a letter to Henry Jackson Waters — whom he’d hired as experiment station director and dean of agriculture — that Waters “experiment with caponizing fowls,” Severance wrote.

One of MU’s pre-eminent researchers was John Connaway — a medical doctor, veterinarian and, later, chair of animal sciences and eponym of Connaway Hall. Jesse would drop by to study the methods and results of Connaway’s experiments. Sometimes, he brought along visiting dignitaries and asked Connaway to explain his research to them. On any given day, the work might entail drawing blood from animals and making serums for inoculations, pulling ticks off diseased cows and applying them to other cows to test different treatments, or simply peering at pathogens through a microscope. Connaway’s studies on hog cholera and Texas fever in cattle led to the control of malaria, yellow fever and other insect-borne diseases in humans.

Jesse’s legacy

By 1905, Jesse’s vision was coming into focus so crisply that he was utterly surprised by a student petition calling for his removal on grounds that he lacked accord with students and alumni. After looking into the complaint, the curators sided with Jesse but expressed concern that the petition had taken a toll on a man “obsessed with the details of his work” and toiling “beyond the limits of his strength,” Severance wrote. The board recommended he take a year off for rest and recreation in Europe. Jesse did not rest, however. He spent his time overseas studying the administration and teaching methods of universities in Germany and France. Within months of his return, doctors pronounced Jesse “broken down by overwork” and advised him to quit, according to Jesse’s letter of resignation, on file at the historical society.

In the end, the man who built a modern university from ashes flamed out from overexertion. Jesse retired at age 55 with his health permanently impaired, though he lived for 12 more years with his wife, Adeline, “in the shadow of the university which had become a monument” to his “creative genius,” Severance wrote.

During his administration, the number of faculty quadrupled, as did student enrollment. The university’s annual income increased more than fivefold, as did the value of its buildings, grounds, books and equipment. (Jesse successfully politicked for ever-increasing appropriations.) However, “It is entirely possible for the University to have grown in all of these directions, and yet in reality to have made but little substantial progress,” the board wrote. The university’s rising stature was the true measure of his success. He raised a “practically unknown” institution to “a position of first rank among the greater universities in the United States,” Severance wrote. Affirming that rank, the Association of American Universities (AAU) — co-founded in 1900 by Johns Hopkins and other research-intensive universities of its caliber — inducted MU in 1908, ahead of most public universities. Today, the AAU is still considered one of the most elite membership-by-invitation organizations in higher education.

On Jan. 2, 1922, New Academic Hall was posthumously renamed Jesse Hall in his honor. The Columns are all that remain of the old Academic Hall. Perhaps not as conspicuously, Jesse’s legacy also continues to this day. “The institution which for nearly seventeen years we have worked so hard together to establish here,” Jesse wrote in his resignation letter, “is but a foundation for the institution of which we are dreaming.”

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.