By Elaine Viets, BJ ’72

The things I learned at Mizzou definitely helped my journalism career. They also helped my second career — as a killer for hire. So far, I’ve shot, stabbed and poisoned more than 50 people.

On paper.

I’m here to tell you about a few more Mizzou alumni who write mysteries. But because these people are all killers for hire, you’d probably like to know who you are dealing with. So, a little about me: My journalism degree opened the doors to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, where I started as a fashion writer. I had all the right qualifications — I was a woman and I wore clothes. J-School had trained me well for my newspaper job, instilling a respect for deadlines, spelling (before spell check), copyediting and reporting.

Being a reporter at the Post-Dispatch was easier than at the J-School’s Columbia Missourian. Back then, everyone in Columbia had been interviewed by J-School students — twice. I was used to doors slammed in my face, phones disconnected, and bored officials fiddling with their pipes or reading the rival Columbia Daily Tribune while I interviewed them.

In St. Louis, most people wanted to talk to a Post-Dispatch reporter. Better yet, I got paid. I graduated to feature writer, humor columnist and, finally, syndicated columnist for United Media in New York.

In the late-’90s, when the newspaper business began floundering, I left to write mysteries. My first series, featuring Francesca Vierling, was a real creative stretch. These novels featured a 6-foot newspaper columnist at a struggling daily, forever battling editors. After that series, my books relied on my reporting skills. The Dead-End Job mysteries each featured a different low-paying job, and I worked most of them for research. For Shop Till You Drop, I sold bustiers to bimbos. For Dying to Call You, I sold septic tank cleaner in a telephone boiler room. I still remember my spiel: “Tank Titan 2000 eliminates odors, large chunks and wet spots.” For Murder with Reservations, I worked as a hotel housekeeper, making beds, scrubbing toilets and the Jacuzzi in the honeymoon suite. (Chocolate cleans right out of the tub, but whipped cream is a bear.) Promise me you will never, ever use the in-room coffeepot. You wouldn’t believe how many men grab that as a handy urinal.

Eventually, I was ready for something grittier that didn’t include wielding a mop and dealing with cranky customers. I started writing the Angela Richman, Death Investigator mysteries. These paralegals of the forensic world got their start in 1978 during a shortage of pathologists to attend the scenes of fatal crimes. They handle the body at homicides and other unexplained deaths while the police deal with the rest of the scene. I took the Medicolegal Death Investigators Training course for forensic professionals at St. Louis University, where I learned all kinds of arcane but useful information. If you see someone with a “Born to Lose” tattoo, turn around and walk away. They’d be voted “most likely to wind up on an autopsy table.” And that’s where I saw a photo of a man with “Born to Lose” tattooed on his forehead — with a bullet hole under it. My fifth Angela Richman mystery, Death Grip, will be published in December 2020.

Down the decades, Mizzou has produced mystery writers with degrees ranging from law to library science. What follows is a short survey of some in the “late-great” category, plus living writers we were able to catch up with — scribes whose novels turn up on the blood-stained bookshelf.

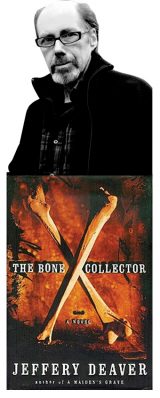

The connoisseur of craft

Jeff Deaver, BJ ’72, is a spectacularly successful writer who gives back to his profession. When he was president of the Mystery Writers of America (MWA) — a job that’s mostly honorary — he traveled thousands of miles to visit all eleven MWA chapters, crisscrossing the country from Florida to the northwest at his own expense. At each stop, Jeff gave chapter members a free writing seminar.

He has sold more than 50 million books worldwide. The Bone Collector was a major motion picture, starring Denzel Washington and Angelina Jolie. Dead Silence, an HBO movie starring James Garner, was based on A Maiden’s Grave. Lifetime adapted The Devil’s Teardrop.

In addition to Jeff’s journalism degree, he graduated from Fordham University law school and practiced law before turning to writing full time.

“I write crime fiction — mysteries and thrillers.” Jeff is careful not to lump those subgenres together. “A mystery asks: What happened? Who killed the parish priest? A thriller asks: What’s going to happen? Will he get there in time, before the world blows up?

“Crime fiction allows me to write the most intensely engaging story and give readers the most intense emotional experience,” he continues. “The core plot of a crime story requires the author keep asking questions and putting up roadblocks. That drives the story: What is going to happen next? Raise conflict, raise questions. The best crime fiction introduces elements that drive other subplots: a romance or a family conflict. These are appropriate in a crime story. They give it depth.”

Despite his artistic comparisons, Jeff doesn’t see himself as a literary figure. “I’m not a prose stylist,” he says. “I’m not a Cormac McCarthy, a real artist who makes the words sing. I don’t have that ability, nor do I want it. I want to take the skills I learned in journalism school and translate them into the clearest prose possible. Learning how to be a reporter — that’s still important. I research all my books, interview experts in the field, prepare my questions ahead of time. I put words together in a pragmatic style.”

A list of all Jeff’s international honors and awards would take the rest of this article. Here’s a sampling: The Mystery Writers Association of Japan named The Cold Moon Book of the Year. The Bouchercon World Mystery Convention gave him its Lifetime Achievement Award. British organizations have given him two honors named after daggers as well as a Thumping Good Read Award — how’s that for a title!

Jeff is particularly proud of The Broken Window, which features his series character, the quadriplegic detective Lincoln Rhyme. He says the book was prescient in the way it dealt with data mining and identity theft. “I sounded the alarm, eight or nine years ago. Crime fiction allows us to deal with all of those issues.”

He will have a new Lincoln Rhyme novel out in 2021, as well as another Colter Shaw thriller.

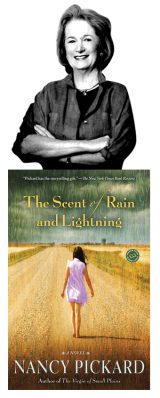

The writerly one

Nancy Pickard, BJ ’67, is a writer’s writer, known for her careful plotting and evocative prose.

In Ring of Truth, she writes, “Like nowhere else I’ve ever seen, the air in South Florida is soft, so soft. After my last book tour, riding home from the airport late of a winter’s night, I opened a window in the backseat, closed my eyes and felt the soft air pat my face like a lover.”

When I come back home to Fort Lauderdale, I feel the same way.

Nancy’s writing also has sly humor. “It just kills me to see somebody break bones on purpose,” she writes. “I want to protest that God and a pregnant lady worked hard on this skeleton, so have some respect.”

Why mysteries? “Because I can’t seem to write anything that doesn’t have a dead body in it,” says Nancy, who is a household name among mystery devotees.

Of her J-School days, she says, “The Missourian probably should have assigned me to the crime beat rather than covering the Department of Motor Vehicles. My only job was to pick up the weekly list of new drivers’ licenses. One day I said, ‘Nah,’ and went to The Shack for beer with some friends. I walked into the newsroom the next day, intending to tell a certain famous professor that I’d been sick, but before I could say a word, he said, ‘So did you get the story about the car crashing into the DMV?’ ”

Learning to make plausible excuses was part of a Mizzou student’s informal training, and our teachers have heard them all. One teacher warned us during the first class that he would only allow two dead grandmothers per semester.

If you haven’t read Nancy’s books, start with The Scent of Rain and Lightning.

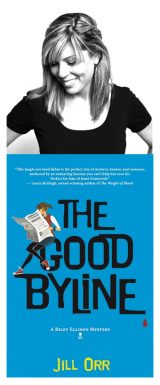

The heartland humorist

“Nothing says ‘You’re going to die alone’ like being asked to judge the three-legged race at the Tuttle Corner Johnnycake Festival because you’re the only one without a partner.” That’s how Jill Orr, BJ ’95, MSW ’00, starts her first Riley Ellison mystery, The Good Byline, and the laughs go on from there.

Humor is a delicate subject to master, as I learned that the hard way at Mizzou. I took a course on printing, which included the antique art of manual typesetting. For one assignment, I made stationery for the man I was dating. It showed Andy Capp, the cartoon boozer, waving a pint beer glass and shouting, “One more, gaffer!”

I got a D on that assignment. My teacher was a devout Baptist, and he was not amused.

Jill’s comedic mysteries — she’s been compared to Janet Evanovich — are set in a small southern town. In The Good Byline, you’ll meet Riley and the inhabitants of Tuttle Corner. Here’s one of my favorite sections: “The day my boyfriend of seven years left me to go find himself, the good people of Tuttle Corner unofficially changed my name from Riley Ellison to Riley Bless-Her-Heart … . People in Tuttle Corner love to bless your heart. It’s code for anything from an expression of sympathy to a vicious insult, sometimes both at the same time.”

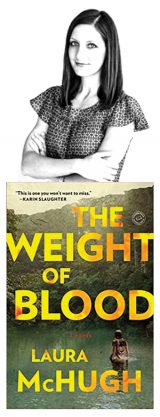

The bleak one

Laura McHugh, MA ’99, BA ’00, didn’t have a particular genre in mind as she drafted her first novel. “I really wanted to write a page-turner, and it wasn’t until I was done that I realized I’d written a mystery.” Her creation, The Weight of Blood, was an instant hit, winning an International Thriller Writers Award. The Sunday Times (UK), Kansas City Star and BookPage named it a best book of the year.

Laura’s dark, brooding novel, set deep in the Ozark Mountains, grabs readers right from the opening line: “That Cheri Stoddard was found at all was the thing that set people on edge, even more so than the condition of her body.” After that, we learn the details: “Cheri’s head snagged on a piece of driftwood. Stuffed into the hollow of the tree was the rest of Cheri’s pieces, her skin etched with burns and amateur tattoos.”

Vogue magazine, of all things, raved about The Weight of Blood, saying it “conjures a menacingly beautiful Ozark setting and a nest of poisonous family secrets reminiscent of Daniel Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone.”

So where did Laura develop her talent for creating menacing beauty? She has a degree in English from Truman State University and consecutive degrees in library science and computer science from Mizzou. “I think computer science helped me the most. That’s the more logical side of my brain. It helps with the plotting,” she says. When it comes to topics, “I start with a story, and I’ve been paying attention to the news, to the stories about human trafficking or the opioid crisis, and they led to the novels.”

Her fourth book, What’s Done in Darkness, is due out in summer 2021. “It’s a small-town drama about home-schooled kids disappearing. These are the kids that fall through the cracks,” she says. Once more, it’s set in the Ozarks. “To me, the beauty, the isolation, the rugged terrain make it a perfect setting.”

The country lawyer

When Nancy Allen graduated from Mizzou’s law school in 1980, she was part of the first generation of women to enter the legal profession. She landed in Greene County, “which had Missouri’s highest rate of sex crimes against children,” she says. “Because I was the only female prosecutor, I got the sex abuse and domestic violence cases. I cut my teeth on incest.” She resolved to write a book about that work, and the result a quarter-century later was her first mystery, The Code of the Hills. “It’s important that we not ignore that issue in fiction,” she says. “Fiction writers can educate their readers about the legal system and societal issues.”

Nancy was in her 50s when she started on the novel. She spent six months writing and another 10 months looking for an agent. “For a year, we tinkered with the manuscript. When she said the vulgar language would have to go, I fired her and got another agent. We parted ways, too. Finally, I got the right agent and she sold it.”

She has written three more Ozarks mysteries and honed her craft — so much so that James Patterson asked her to collaborate with him.” Yes, that’s the James Patterson, the one whose novels go straight to the top of the bestseller list. Working with Patterson, one writer told me “is like taking a master’s course in mystery writing.” Not to mention major moolah and recognition. Nancy’s first book with him was Juror No. 3, and two more have followed.

“In the beginning, I was peddling a book that no one wanted to buy. It was so hard to get my foot in the door, and now they’re coming to me.” Looking back, she counts herself lucky to have entered law school back when women were a novelty in the field. “We had to be tough. I had to battle to enter a new profession, and that was good experience for entering the publishing world in New York.”

Stay tuned for her next series, Vigilantes Anonymous, a high-concept thriller about a group of misfits fighting injustice in Manhattan.

The ground-breaker

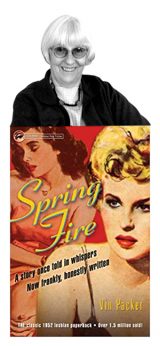

Marijane Meaker, BA ’49, has always been something of a rebel. Even way back in boarding school, she was expelled for using photos of faculty members as a dartboard. She took a detour at Mizzou, too, switching majors from journalism to English after flunking that J-School bugaboo, economics. By the time I went to Mizzou, they had a special class for math-challenged J-School students, Econ 51. Teaching it must have been like teaching an elephant to disco. Meaker went on to become a groundbreaking writer who had four careers under four pen names, authoring landmark books under each.

As Vin Packer, Marijane wrote some 20 novels, mostly mysteries. One was Spring Fire, considered the first paperback dealing with lesbian issues. Published in 1952, it reportedly sold 1.5 million copies. The prejudice and prudishness of the times would not let Packer tell the story her way — lesbians could not live happy lives in fiction. Reportedly, her editor required that one character must say she’s not a lesbian and the other must be “sick or crazy.”

As Ann Aldrich, Marijane wrote five nonfiction books about lesbian issues including We Walk Alone and We, Too, Must Love.

She also wrote more than 20 young adult novels as M.E. Kerr. Her books dealt with many adolescent issues, including racism, sexism, AIDS, homosexuality and drugs. She won an award from the American Library Association for her “significant and lasting contribution to young adult literature.”

She has a wicked sense of humor. In her autobiographical Me, Me, Me, Me, Me: Not a Novel, Meaker confessed that, at the beginning of her career, she pretended to be a literary agent. Her clients? Meaker’s many pen names.

She also wrote for younger audiences as Mary James and four books under her own name, Marijane Meaker, including one about her affair with Patricia Highsmith, Highsmith: A Romance of the 1950s.

Marijane always made her living as a writer. She never needed a second job to support herself — a rare feat for a writer at any time. Many of her books remain in print. At 93, she is “not focused on work these days,” according to Michelle Koh her friend, fan and “webmistress.”

The franchise

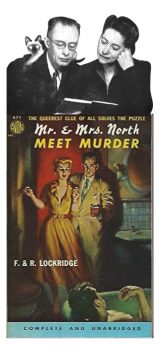

Mystery writers Richard, JOURN ’20, and Frances Lockridge were married, and so were their characters. With Frances’ plots and Richard’s writing, they created a blockbuster series. During the 1940s and ’50s, masses of fans waited eagerly for the next adventure of the cosmopolitan Mr. and Mrs. North.

After Mizzou, Richard served in the Navy during World War I. In 1922, while working at a Kansas City newspaper, he married another reporter, Frances Louise Davis. They moved to New York, where Richard worked for the New York Sun. He also contributed to The New Yorker, writing comedic sketches about a couple called the Norths. Why that particular compass direction? “It was merely lifted from the somewhat amorphous, and frequently inept, people who played the North hands in bridge problems,” Richard once explained. Bridge was all the rage then, and bridge columns, featuring the hapless north hand, were popular features. “Pam North is a flighty homemaker, prone to malapropisms and random trains of thought. Jerry North is an editor at a publishing house, who often understands and translates for his wife,” writes mystery biographer Jeffrey Marks. Comedienne Gracie Allen was perfectly cast as Pam North in a 1943 movie version.

The Mr. and Mrs. North mysteries were the brainchild of Frances. She came up with the idea for the first mystery but hit a snag with the plot, which included a body in a rowboat. Richard used her idea and the characters he’d created for the New Yorker humor sketches. The rowboat became an apartment bathtub, and the victim lost his clothes, as well as his life.

The Lockridges’ creation resulted in a small industry: 26 mysteries, which were adapted for the movies, theater, radio and finally TV. Spinoffs included the 22-book Lt. Heimrich series, the ten-book Nathan Shapiro series, and the six-book Paul Lane series.

“The stories include copious amounts of feline help,” Marks continues. In the first book, The Norths Meet Murder, they have a cat named Pete. Pete was soon shuffled off the stage in favor of Toughy and Ruffy who later gave way to Vodka, Sherry and other liquor-named pets.”

But the series wasn’t all cats and cocktails. “Of all the mystery wives, Pam is perhaps the one most often endangered,” according to Murderess Ink. “Not a venture goes by in which Pam isn’t mauled.”

The couple were co-presidents of Mystery Writers Association and won its inaugural Edgar Award. Most of their books are still available as e-books, paperbacks and hardcovers. So are the DVDs of the TV shows, starring Richard Denning and Barbara Britton, which you can also find on YouTube.

Frances died in 1963. Richard remarried and continued writing until his death in 1982, but he never wrote another Mr. and Mrs. North novel.

The literary one

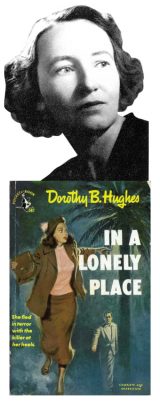

Dorothy B. Hughes, BJ ’25, has been called a “renaissance author.” The J-School graduate started her career as an award-winning poet, moved on to mysteries and criticism, and also wrote the definitive biography of Erle Stanley Gardner, the creator of Perry Mason.

Crime fiction authority Sarah Weinman calls Dorothy the world’s finest female noir writer. “She built worlds — especially in the early New York novels and the later ones set around Los Angeles’ twisting streets and in New Mexico’s wide-open spaces — that were vivid with bright colors, glittering baubles and big dreams yet never felt cartoonish.”

During her time at Mizzou, Dorothy wrote and published poems that became part of her 1931 collection Dark Certainty, winner of a Yale Younger Poets Prize. Nine years later, she wrote her first hardboiled novel, The So Blue Marble. Thirteen more novels followed, two of which became major Hollywood movies: The Fallen Sparrow with John Garfield and Maureen O’Hara and In a Lonely Place with Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame.

In the early 1950s, during the shameful McCarthy era, Dorothy was blacklisted in Hollywood. She became a successful critic and won a coveted Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Later, she’d receive an MWA Grand Master Award for literary achievement.

Dorothy’s last novel, The Expendable Man, includes these haunting words: “When man wants an evil, he’ll always

find someone evil to supply him.”

Are you a fan of mysteries? Tell us about your favorite Mizzou mystery authors at mizzou@missouri.edu.

To read more articles like this, become a Mizzou Alumni Association member and receive MIZZOU magazine in your mailbox. Click here to join.