June 12, 2020

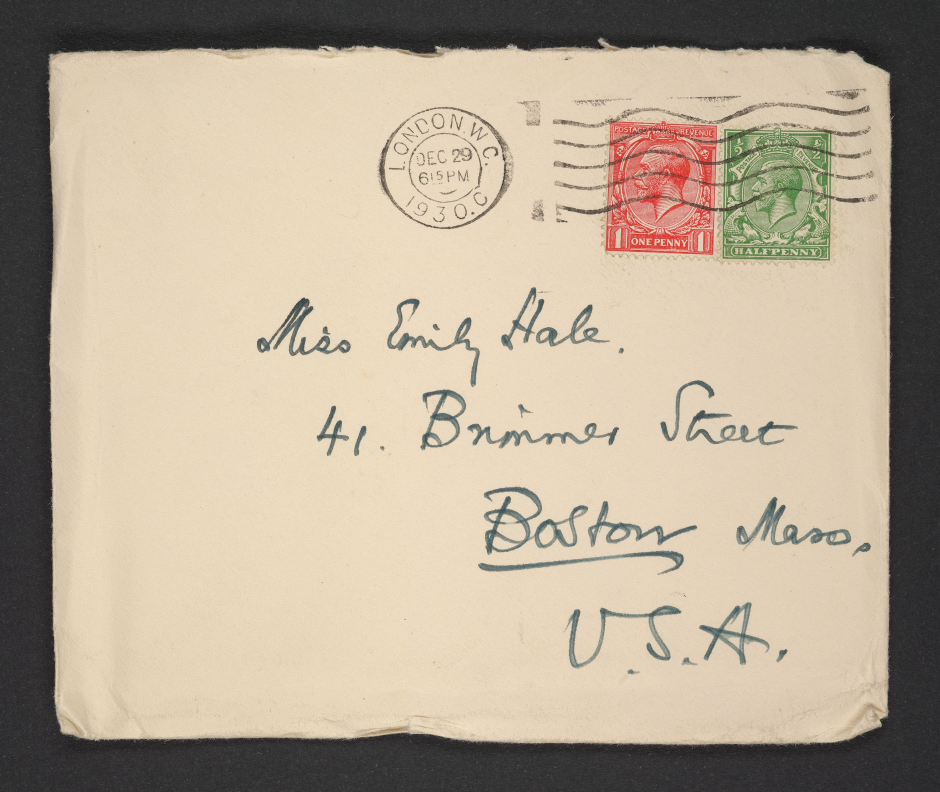

Frances Dickey, a T. S. Eliot scholar, was surprised when she read Eliot’s first letter to Emily Hale, dated October 1930.

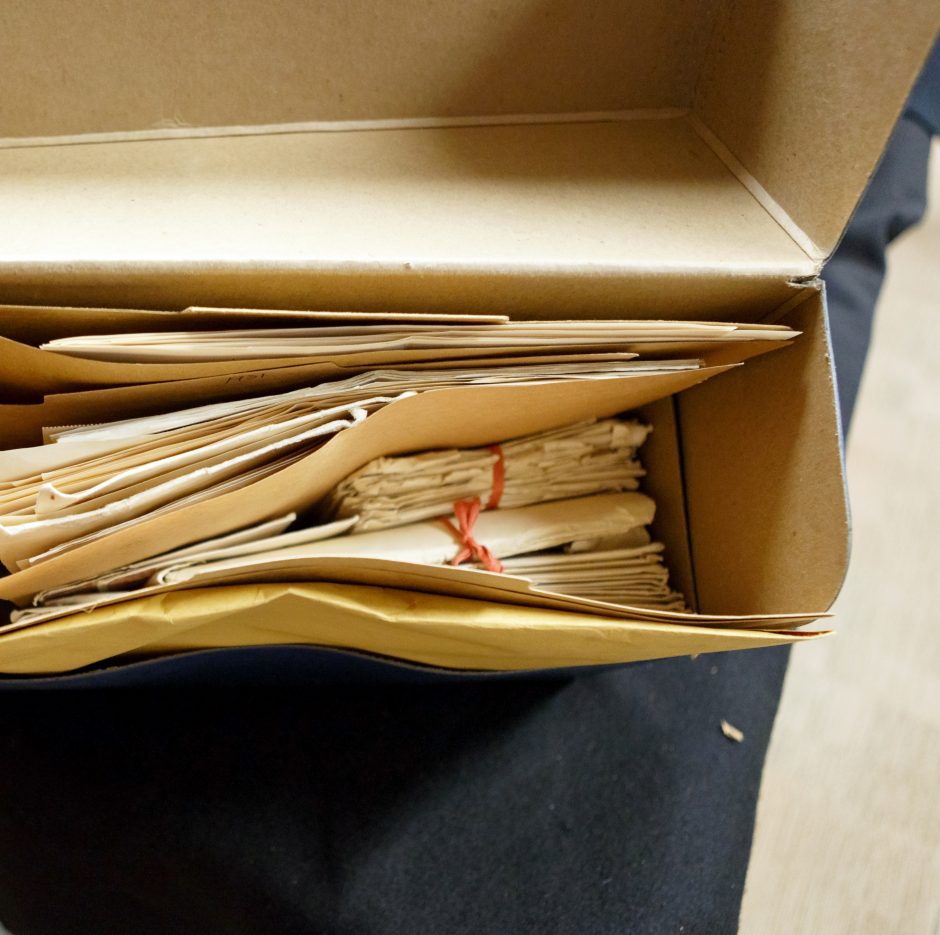

“The poet tells her everything about his life, pours out his heart to her and just shows a side of himself that was previously unknown to scholars of his work,” said Dickey, an associate professor in the Department of English at the University of Missouri. “Emily Hale saved every one of those letters.”

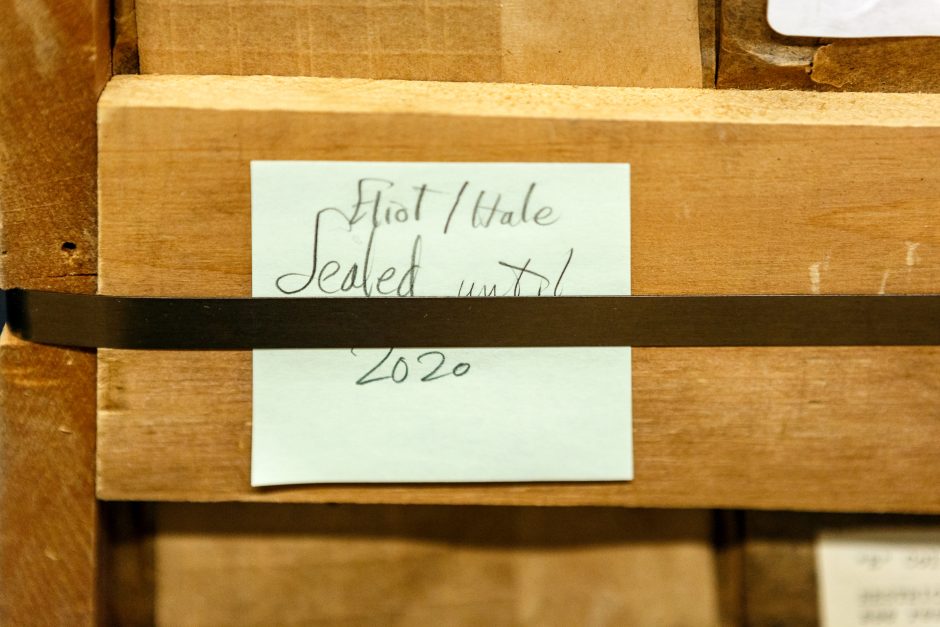

Eliot wrote to Hale, a woman he had known since his college days, on a regular basis from 1930 to 1957. Over a thousand of Eliot’s letters were donated by Hale and sealed away at Princeton University under the condition that the letters were not to be opened until 50 years after her death — January 2020.

Dickey received an MU Research Council grant to study the letters once they were revealed to the public earlier this year.

“Scholars have known all along that the letters were locked away, but we didn’t know what was contained in them,” she said. “Eliot was a prolific letter writer, but many are just boring business letters. It was quite a shock to read his first letter from October of 1930 in which he tells Emily about his love for her.”

Dickey has been chronicling her findings in a blog that had over 2,000 readers in just the first week of January after the letters were opened.

A Missouri connection

Eliot, often considered by literary scholars as one of leading poets of the 20th century, is best known for his poems “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and “The Waste Land.” Written after World War I, Dickey said “The Waste Land” is often considered his greatest work, with memorable lines including “April is the cruellest month.”

Eliot was born in St. Louis, and it was his Missouri connection that drew Dickey’s interest to his work.

“Living in Missouri has focused my mind on Eliot,” she said. “His first sixteen years in St. Louis formed his urban imagination in ways that are clearly reflected in his poetry. Eliot scholars who have not visited St. Louis or have only been once or twice haven’t been able to appreciate his debt to the city.”

Eliot’s St. Louis influence can be found in several of his works, according to Dickey. In “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” the speaker wanders grimy city streets inspired by the St. Louis Eliot grew up in. Eliot describes the Mississippi River as “a strong brown god—sullen, untamed and intractable,” in the opening of “The Dry Salvages,” the third poem in “Four Quartets.”

“I think many Missourians might not know that Eliot was not only born in St. Louis, but also grew up there, and his poetry reflects that upbringing,” she said.

The poet’s grandfather, William Greenleaf Eliot, founded Washington University in St. Louis, and his family members were prominent figures in the city. Dickey also discovered family letters in the archive of the Hydraulic-Press Brick Company, where Eliot’s father worked as president, that contributed to her research on the poet.

The International T.S. Eliot Society, an association of people interested in the poet’s life and work, meets in St. Louis for their annual meeting. Dickey said the meeting’s proximity to Columbia has helped her network with other scholars and fans of his work.

“Living in Columbia, it is easy for me to go to those conferences, and I meet amazing Eliot scholars as well as fans of his poetry each year,” she said.

An extensive correspondence

Eliot met Hale in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as a young man, but was too shy to ask her to marry him. He left the U.S. for England in 1914 but was unable to travel back stateside due to the start of World War I. Dickey said Eliot became involved in an unhappy marriage in England and got back in touch with Hale in 1930.

Eliot considered Hale his muse, and he credited her with his conversion to the Anglican Church, Dickey said.

“He tells her that she has led him to God, and she was the guiding light of his religious conversion, going as far as saying that he has written the poem, ‘Ash Wednesday,’ with her on his mind,” she said.

Along with inspiring the poem “Ash Wednesday,” Eliot also told Hale that she is the Hyacinth Girl in “The Waste Land.” Some scholars had speculated this to be true, but Dickey said the letters to Hale confirm that these parts of his poems were autobiographical.

“It’s very rare to get a poet telling you what his poem is about, especially a poet as enigmatic as Eliot,” she said.

Dickey said that one reason Eliot’s work has had such an impact on American literature and culture is because his words capture the disruption of modernity. “The Waste Land” explores the way the world was speeding up and changing with technology in the 1920s, which still resonates with readers today.

“Eliot wrote so many lines that are memorable and thought-provoking in that way,” Dickey said. “I think that’s why he remains important in American cultural life today.”